Every contemporary work of art is the cumulation of centuries of cultural history. In the case of Japanese literature, we’re looking at about 1,000 years of written prose and poetry. It all started in the Heian period (794-1185) with Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting and member of a minor branch of the powerful Fujiwara clan. Most importantly, she is author of one of the most important pieces of literature in the world, The Tale of Genji, published in the early 11th century. For the sake of comparison, the first novel in modern European history is thought to be Cervantes’ Don Quixote, which was first published in 1605.

(Source)

Heian Aristocracy

While Shikibu was undoubtedly a pioneer of fiction in Japan, not much is known about Shikibu, including her given name. At the time, the maiden names of elite women weren’t recorded. The name Murasaki Shikibu was allegedly created based on one of the characters appearing in The Tale of Genji (Murasaki) and her father’s status (Shikibu, which is Japanese for “Ministry of ceremonies”), though historians still dispute this theory.

Like many women of her status around the world, she lived relatively comfortably, though the aristocratic lifestyle also came with a few restrictions. The Heian period elite favored high education and culture, and often powerful individuals were also the most cultured ones.

Men would learn everything from poetry and languages to law and politics. Women, however, were restricted to the arts because that is what was considered attractive; Chinese was an important language to master for those directly involved with the court and to participate in literary circles, but women usually could not study it.

This did not stop aristocratic women from investing themselves in the creative fields, however, using hiragana and contributing greatly to the poetic diary genre. The Diary of Lady Murasaki along with Sei Shonagon’s The Pillow Book are the main representatives of the genre to this day.

Through fragments of Shikibu’s diary and fiction work, historians were able to learn about the unique aristocracy of classical Japan. At the time, poetry and prose were written heavily based the lives of their authors, but Shikibu’s stood out from the masses by being clearly a work of fiction — though many argue that the stories of The Tale of Genji were inspired by real-life events.

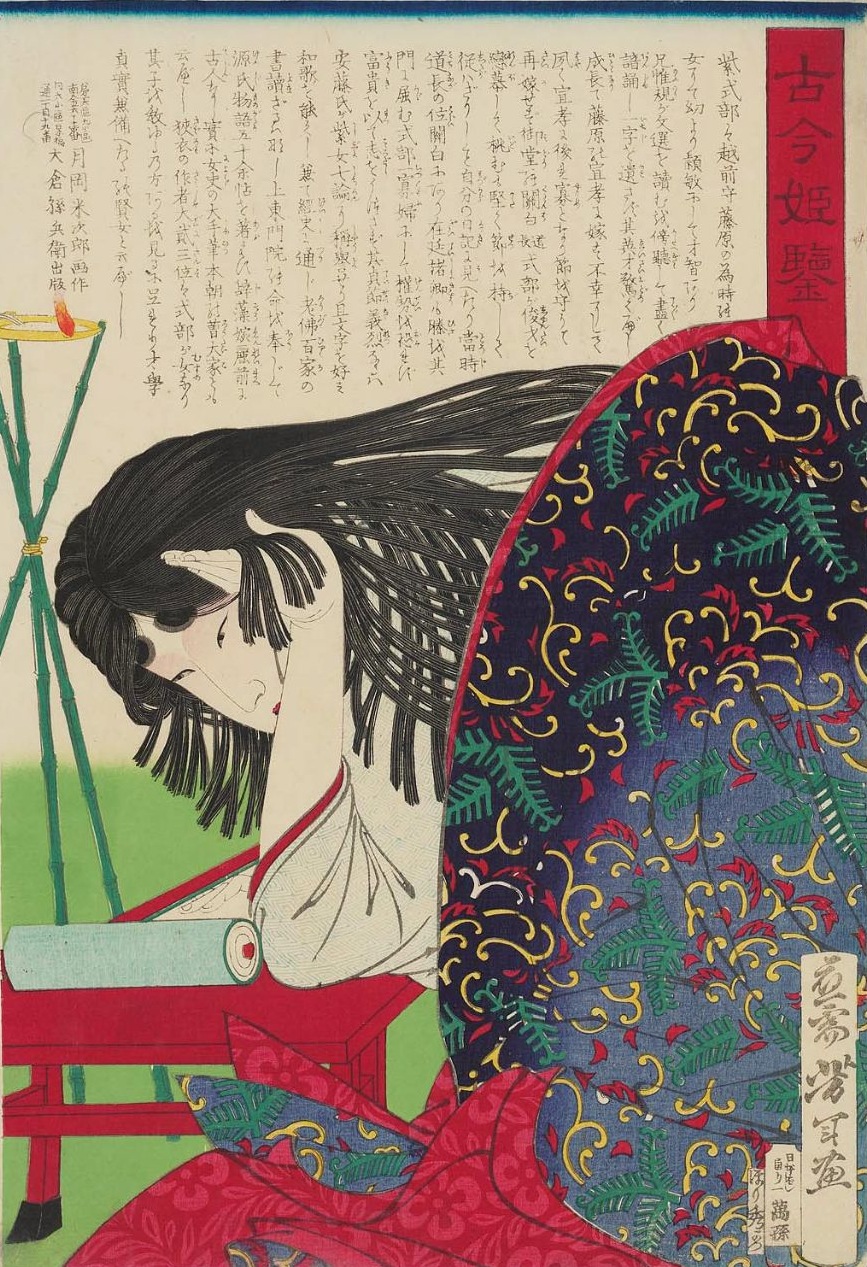

Ilustration of the The Tale of Genji, ch.20–Asagao, traditionally credited to Tosa Mitsuoki (1617–1691), part of the Burke Albums, property of Mary Griggs Burke. Source: The Tale of Genji: Legends and Paintings

The Tale of Genji

The Tale of Genji is thought to be the first written work of fiction in the world. It is uncertain whether Shikibu wrote the complex story in a couple of years or over decades, but what is certain is that this comprehensive piece of literature is a portrait of the Heian aristocracy in all its complicated hierarchies and polyamorous tendencies.

What’s even more impressive is that despite the long list of characters and appearances throughout the book, the story still only surrounds what was at the time less than 1% of the population, the highest elites.

Reading through the chapters allows for a vivid idea of what it was to be a man or a woman in the Heian period along with the attached expectations. The protagonist, Genji, is the archetype of a hero of the period, the perfect man. Son of an ancient emperor, his right to the throne was removed and he was demoted to a commoner, when he changed his name to Morimoto.

The Tale of Genji essentially follows his numerous sexual adventures with various women from the aristocratic circles. While it might seem like a trivial story, the cultural importance of the novel rests in its infinitely rich subtext, which reveals the surprisingly restricted lives of the women Genji crosses path with while he, in contrast, wanders the kingdom.

Besides many suggestions of a male-dominated society, the novel is proof of something that might be even more crucial: women undeniably played a great role in the propagation of the arts. In fact, while the Heian period saw many failed attempts to revolutionize Japanese governmental policies, what is left of it is a rich attachment to culture that Japanese society still holds on to today.

The prose and poetry written in hiragana by women of the court meant that lower classes (though not quite peasantry yet) could enjoy them, too. In other words, the Heian period is seen as a time when the art world in Japan was born and throve infinitely from then on. Not only is Shibiku an important historical figure because of her legacy in Eastern and international literature, but she is a symbol of a time in Japan when women were succeeding in ways that had never been seen before.

Murasaki Shikibu in Popular Culture

Shikibu is one of the most significant historical figures in East Asian cultural history, and throughout the millenniums that followed, she remained a staple in Japanese high school and college syllabi, much like Shakespear in Europe and North America.

It has seen many important translations and interpretations, as well as received its fair amount of criticism. In Japan, The Tale of Genji is commemorated on the rare 2,000-yen note and the Japanese beautyberry plant is named Murasaki Shikibu after her.

Like the story of the 47 ronin, The Tale of Genji was adapted to the big screen quite a few times, with the latest being the feature film Genji monogatari: Sennen no nazo (2011). In recent years, Murasaki Shikibu herself has made appearances in mobile games such as Fate/Grand Order and Monster Strike, where her attributes are inspired by her works.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7IINzd7lv4o

Additional reads

Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagon: Two pioneering women in Japanese literature

Murasaki Shikibu: Badass Women in Japanese History

The Tale of Genji (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Where would we be without the words of Japanese women?

The Story at the Heart of Japanese Culture: “The Tale of Genji”

Feature image: Murasaki Shikibu sleeping, c. late 17th century, Kikuchi Yōsai | Wise Personages Past and Present containing portraits of more than five hundred loyalists, royal retainers and heroic women in history (1868)