When you live in a democracy, it’s nice to believe there’s a free and independent press, full transparency of media information dissemination and a hard-boiled sense of journalistic integrity pervading the news corps. This notion has deteriorated across much of the world in recent years, but in Japan, where true watchdog journalism has struggled in the postwar era, the current tale makes for somber reading.

Japan scored woefully low in the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index 2022. At 71st, it fell below Burkina Faso, where it’s not unheard for boots-on-the-ground reporters to be deported or even killed; Armenia, where the mass media market is rife with political corruption; and Haiti, which was cast into a further state of lawlessness following the assassination of its authoritarian leader, Jovenel Moise, in 2021.

That one of the world’s most developed democracies has plunged down the rankings is especially jarring given Japan occupied 22nd position as recently as 2012. But the recent descent hasn’t arrived out of the ether; rather, it’s been driven by systemic practices that have eroded the accessibility of public-serving information and to punish those who divert from the agreed-upon MO.

The Offenders

Five major media conglomerates — Yomiuri, Asahi, Nihon Keizai, Mainichi and Fujisankei — have oligopolistic control of mainstream news in Japan. The Yomiuri Shimbun is the world’s most circulated newspaper at 7 million daily readers. Furthermore, public broadcaster NHK is the second largest institution of its kind worldwide and holds huge sway in the public sphere. This becomes a major issue when vested interests start dictating the editorial direction of news outlets.

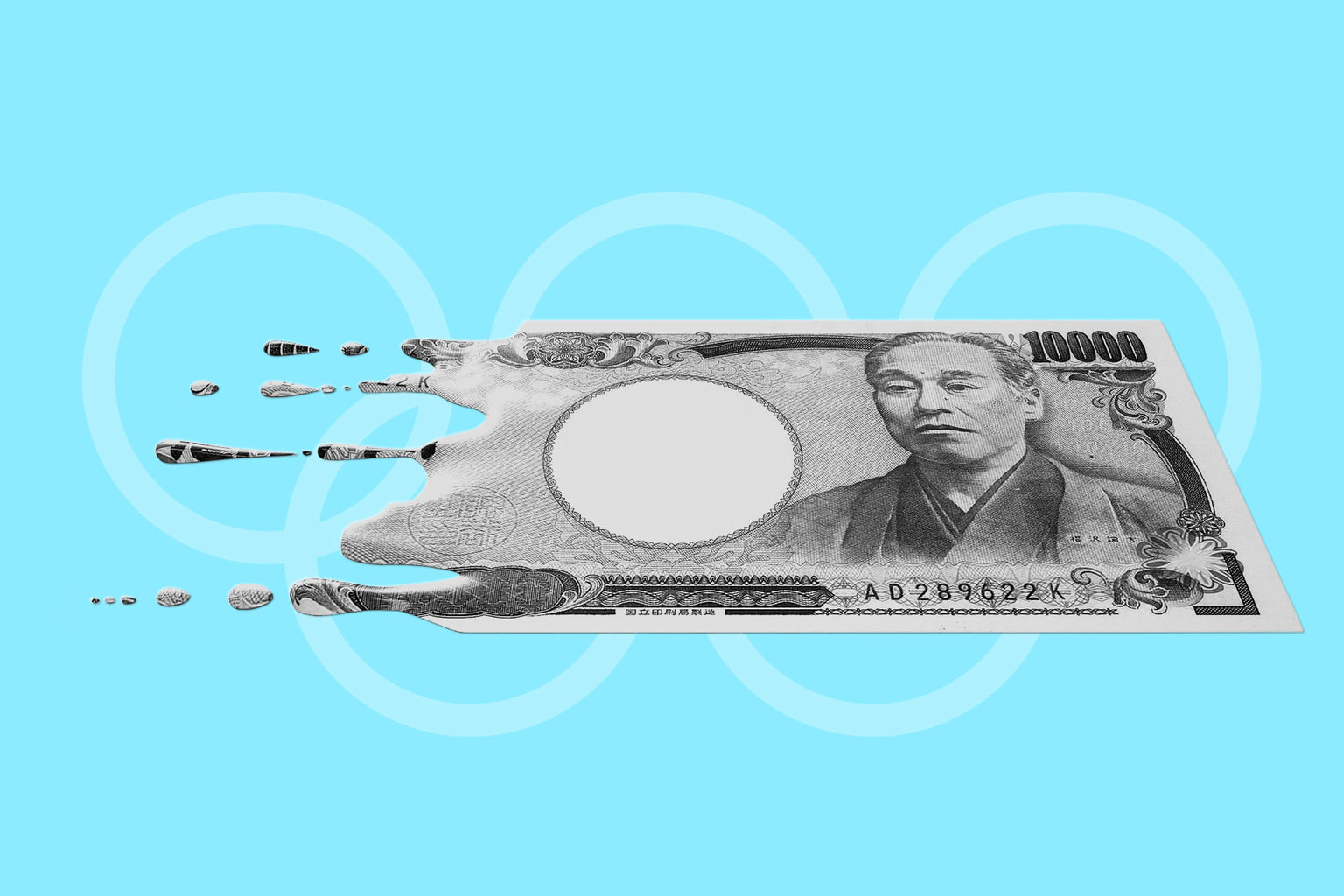

A recent example involves NHK, which adopted an agenda-cutting practice of limited reporting on the risk of Covid-19 prior to the postponement of Tokyo 2020. Alongside commercial broadcasters, in a group called the “Japan Consortium,” NHK paid the International Olympic Committee (IOC) a record ¥66 billion for rights to cover the Games. This financial investment, as well as NHK’s inherent political influences as a public broadcaster, represented a clear conflict of interest when covering issues that would have contravened the combined government and IOC narrative — that the Olympics should go ahead.

Image by Anna Petek

Clandestine reporters’ clubs, called kisha kurabu, are also among the offenders. They played a significant role during the late-Shinzo Abe’s second prime ministerial tenure and off the back of government censorship following the 2011 triple-core meltdown in Fukushima. Kisha kurabu are comprised of journalists working at the major Japanese newspapers and TV stations, with foreign reporters and freelancers generally restricted. The member journalists are given exclusive access to official sources and in order to maintain said access, are required to toe the respective party line.

This was most apparent in the immediate aftermath of the 2011 disaster, when Japanese editors representing the major dailies forbade their journalists from traveling to within 30 or 40 kilometers of the offending nuclear plant, instead choosing to pump out stories that mirrored the message of officialdom: that there was no immediate danger to human health. Moreover, mainstream news outlets refused to use the word “meltdown” in their coverage, favoring milquetoast alternatives such as “an exploding-like event.”

This led to months and years of Japanese press reporting favorably on the institutions complicit in the coverups of the disaster while the foreign press narrative began to cut a much bleaker image of the relevant actors’ malpractice.

Then there’s Japan’s legal framework, which technically guarantees press freedoms, although recent laws have hindered independent, objective and investigative reporting. The 2013-approved State Secrets Protection Law reinforced surveillance regulations across the country, allowing the government to withhold information if it’s deemed a matter of national security. The law also permits punitive punishments for whistleblowers and journalistic leaks, including up to 10 years imprisonment and a ¥10 million fine. More worrying still, what constitutes a state secret, and therefore how this law is arbitrated on, is down to government discretion.

More recently, in 2021, the government enacted a further national security regulation which could blunt investigative efforts in areas near “certain important facilities” — again what falls into this category is largely open to interpretation.

Journalists interviewing women wearing kimono in Asakusa

The Reality of the Situation

Often journalistic practices in Japan are reminiscent of advertorial writing, where information is divulged in return for creative control of the published content. This is an accepted and transparent form of information dissemination when promoting regional tourism or a flashy new bullet train, say, but sets an autocratic precedent for reportage on natural disasters, institutional malpractice, government corruption or human rights infringements.

This is troubling as a journalist, but even more so as a resident. When I lived in China, I was well aware that I was being spoon-fed a CCP-approved narrative by the few English-speaking news channels to populate my cable box. But in Japan, I expected something different. It’s clear the country has hit a particularly enigmatic point in its already enigmatic history.

Japan continues to shed its global relevance by remaining closed off to the outside world. Its stifling patriarchal work culture, indicated by its languishing position of 116 of 145 surveyed countries in the 2022 Global Gender Gap Report, is causing bright young minds to look elsewhere for work. Foreign direct investment (FDI) remains almost absent — Japan ranked 201, dead last, in a recent survey of national FDI in relation to GDP (North Korea was ahead at 200). And now, once again, the inability of its press to function as one would expect in a democracy has been laid bare.

Perhaps once viewed as quirks by a society that was struggling to reinvent itself in the wake of postwar hardships and a subsequent economic surge and collapse, these issues are now seriously hindering Japan’s attractiveness and marring its much-vaunted cultural soft power image. Which, of course, has deleterious effects at home too.

There are certain things the citizenry ought to expect in a democracy. Not least of which is a press that upholds standard journalistic principles. That the faulty system is getting more entrenched, should be a cause for concern indeed.

Feature image by Anna Petek