Growing rice isn’t the easiest of tasks even today, but a few hundred years back, it was a significantly more complex operation. Rice seedlings first had to be matured in separate beds and then removed by experienced farmers so as to not damage their roots. The seedlings would then be planted in the fields by young women due to the belief that their fertility could transfer to the crops and bring forth a bountiful harvest. It was backbreaking, monotonous work that the entire village got in on, often while singing songs to alleviate the boredom.

But in the end, the appreciation shown by landowning samurai made it all worth it. Just kidding. They never even got a thank you from them. Which paired great with all the rice they didn’t actually get to eat.

The Luxury Japanese Staple

Up until around the mid-15th century, peasants made up about 90 percent of Japan’s population. As the samurai class grew and hit its peak during the Edo Period (1603–1868), the number of farmers around the country fell to 80 or so percent. The overwhelming majority of those farmers didn’t live off rice. Their diets usually consisted of porridge made from millet, barley, wheat or a mix of all three. Pickled vegetables, miso soup and the occasional fish (usually dried) also made appearances on the farmers’ tables but as for the rice they grew, almost all of it went to the royals, the samurai and wealthy townspeople.

According to some anthropologists, it was only around the 1700s that farmers started eating rice more regularly. However, the grain hadn’t become a true staple available to the majority of Japanese people until maybe the mid-19th century. Before that, commoners only enjoyed rice and rice products like mochi cakes or senbei rice crackers on special occasions such as New Year celebrations, the Obon Festival, weddings or harvest feasts.

Japanese family meal old illustration. Created by Neuville after photo by unknown author, published on Le Tour Du Monde, Ed. Hachette, Paris, 1867

The Rice Economy

During the Edo Period, rice wasn’t just food for Japan’s rich and powerful. It was also the basis of the country’s entire economy, which ran on koku. A koku of rice was equivalent to 180 liters (48 US gallons), or about as much rice as an adult (non-commoner) could consume in a year. When an Edo feudal domain was appraised for tax purposes, its value was expressed in how much koku of rice you could potentially get from the total economic output of the fief. That amount also determined how big of a castle the domain’s lord could build.

Feudal lords also paid their retainers in koku of rice, though the majority of them took the rice stipend’s monetary equivalent instead of the actual grain. Still, the koku system had to be backed up by actual, physical rice. Before it could be traded, the rice had to be collected from the farmers as tax, which started around the Kamakura Period (1185–1333). Exactly how much rice the landowners took from the farmers differed throughout history, but it could be anywhere between a third and two-thirds of everything.

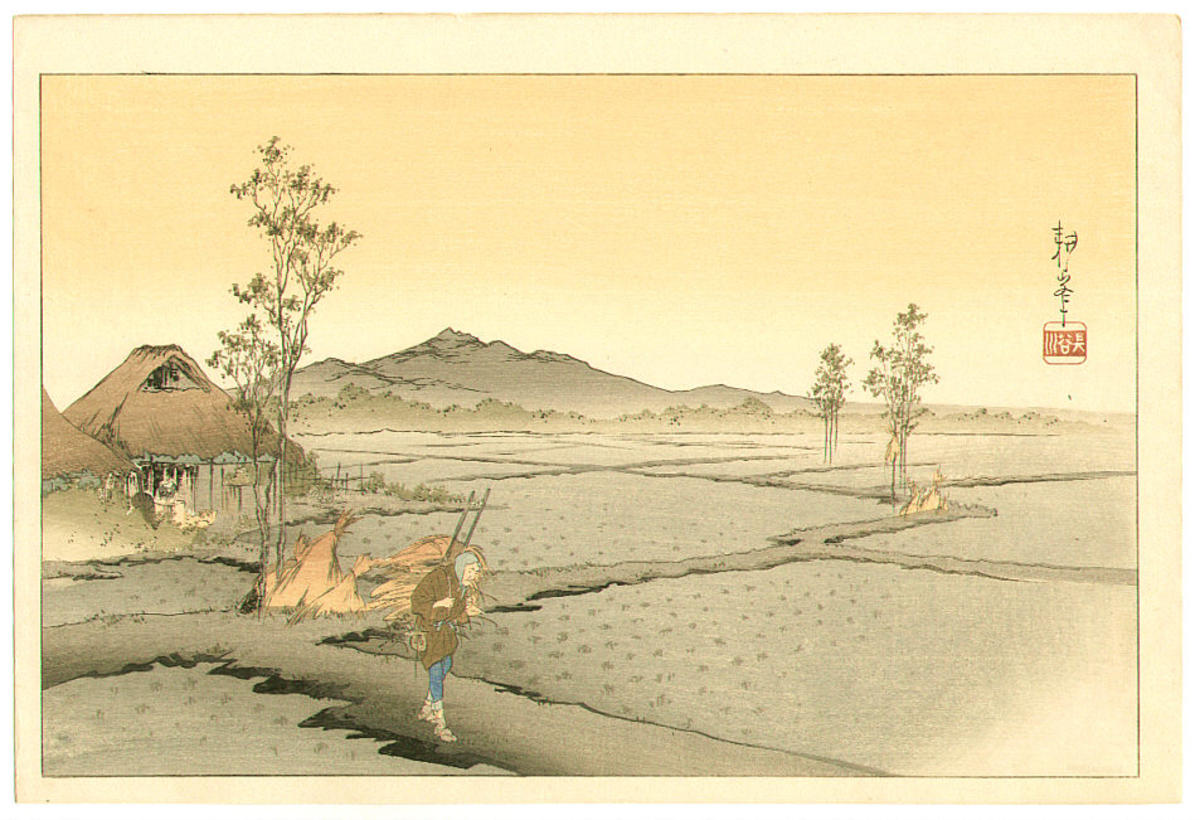

Artist: Koho Shoda 1871?-1946? Publisher: Hasegawa Technique/Medium Woodblock print

Some tried to get around this by bribing official rice-output surveyors sent by the government. Or, by planting secret, undeclared rice fields. But even then, they usually traded the extra rice for other goods instead of eating it. Many farmers actually had so few first-hand (or rather “first-mouth”) experiences with rice that a death ritual emerged where a dying farmer was comforted with the sounds of grains of rice inside a bamboo tube, so that they could at least listen to the thing they so rarely tasted.

A Punishing Profession

An ordinance issued in 1649 explicitly forbade farmers from eating rice. They were told to instead live on millet and vegetables and even the fallen leaves of plants if they had to. They were expected to eat just about anything they could get their hands on, just not rice. Exceptions could be made during harvest festivals and the like. They were also forbidden from enjoying tea, sake and tobacco. There’s more: their clothes had to be made from cotton or hemp. Silk, which they also cultivated, was reserved for more “important” people.

Additionally, from the mid-16th century, it was illegal for farmers to abandon their lands and move to towns. This forced many who wanted to leave the farming life behind to sneak off in the middle of the night. Fun fact: men caught romancing married women were sometimes sentenced to work on those abandoned rice fields. And when a profession can be used as a punishment, that should tell you how pleasant it was.

Thankfully, things have improved considerably since then and now all Japanese people enjoy rice on a daily basis. Another fun fact though: according to some surveys, the majority of Japan now apparently prefers bread for breakfast.

Japan’s history is full of fascinating stories. Here are some more to read: