Issues around imperial succession have been in the news of late and much of the commentary has convinced me we are failing as a species. In case you missed it: Princess Mako, niece to current Emperor Naruhito, has just married her college sweetheart Kei Komuro. And the local media is once again up in arms.

Since the couple formally announced their intent to marry in 2017, the press has launched a salvo of smear campaigns and character assassinations Komuro’s way. His mother’s debts. The question of his ancestry. His eligibility to practice law. The promiscuity of his university years (Gasp! Can you imagine?). And eventually, his choice of hairstyle came under intense scrutiny by a bloodthirsty tabloid corps who presumably burned their moral compasses the minute they signed the dotted lines on their Faustian contracts.

Passing pointed judgment on the betrothed of a 30-year-old royal may gel with traditional imperialist concepts of honor and duty. That does not make it any less mean-spirited. Princess Mako was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the wake of the onslaught, yet the media showed no signs of abating. Nor does it make it any less redundant. Primarily, because Mako is a female and therefore stood no chance of succeeding to the throne or producing heirs under current Japanese law.

A Brief History of Japan’s Royal Succession

The statute of Japan’s Imperial Household Law of 1947 was one of many legislative changes thrust upon the nation during the days of US occupation. Said law states, “The Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by a male offspring in the male line belonging to the Imperial Lineage.”

This wasn’t always the case. Initially, succession followed a general rule of agnatic seniority, meaning a monarch’s brother took precedence over a monarch’s son. During this time, descendants, male or female, from the patrilineal lineage of first Emperor Jimmu could ostensibly rule the empire given the right set of circumstances.

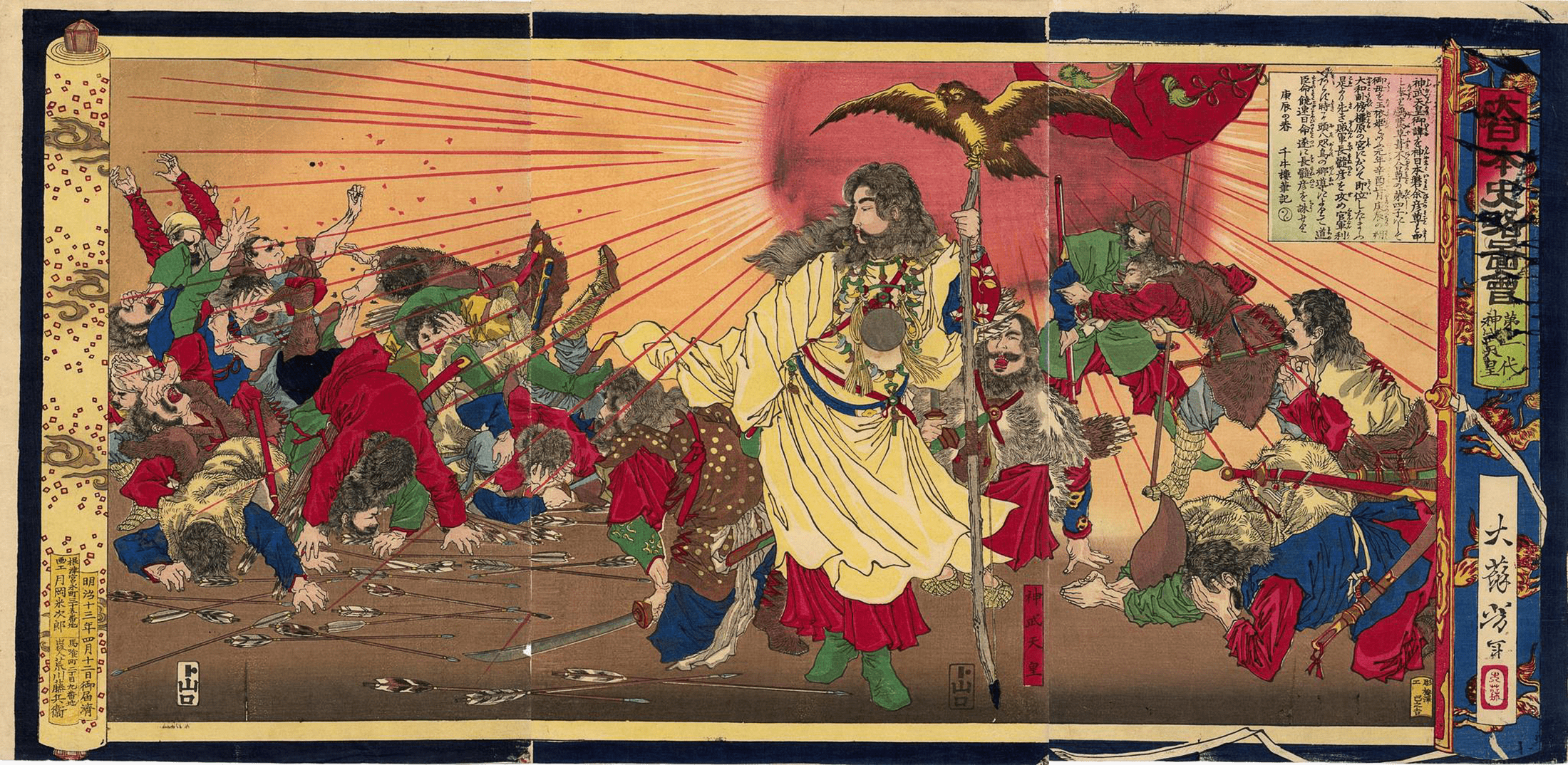

Emperor Jimmu, ukiyo-e by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1880)

But this was also a time of polygyny – entitling a man to have several wives – which resulted in a surplus of potential male successors. If one successor had difficulty fathering male heirs, he would simply upgrade one of his concubines and demand they provide him with a boy.

There is a precedent, albeit a weak one, for female rulers. Eight have reigned throughout the royal family’s 2,700-year history, most recently in the form of Empress Go-Sakuramachi, who abdicated in 1771. Usually, this happened when a suitable male heir was not yet of age, and only if the empress in question was descended from the male imperial bloodlines.

September 23rd, 1740 – Empress Go-Sakuramachi, 117th monarch of Japan and last of eight women in the history of Japan to take on the role of empress regnant, is born. #history #anniversary #born #BornThisDay #September #Japan #JapanHistory #Empress #Monarchs #HistoryOfJapan pic.twitter.com/qx3P0uiCON

— EmperorsVault (@EmperorsVault) September 23, 2018

Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, however, the law changed, directly outlawing female succession. Then, in 1947, it was tightened further by only allowing descendants of the male line of Emperor Taisho (the current emperor’s grandfather), to take the Chrysanthemum Throne.

This drastically slashed the pool of successors, leaving just three remaining today: 85-year-old Prince Hisahito, 55-year-old Prince Akishino and 15-year-old Prince Hisahito. With Emperor Naruhito already 61 years of age, the youngest Hisahito is the likely heir. And the Imperial Household best hope he matures into a man of rampant fecundity.

Members of the imperial family on the balcony of the palace are greeted by the people. Photo by dimakig / Shutterstock.com.

The Experts Vs. The People

The law also states, in rather unwieldy terms: “In case a female of the Imperial Family marries a person other than the emperor or the members of the Imperial Family, she shall lose the status of the Imperial family member.” Hence Princess Mako’s departure from the realm and her newfound status as a “commoner.”

Former Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, a proponent of preserving the male line, convened a panel earlier this year to assess the legislature around these issues. It reaffirmed two of my beliefs.

Firstly, that these panels of experts, which the government loves so dearly, are in fact councils of stubborn ideologues. Secondly, they have their minds made up long before a discussion threatens to get underway.

The mostly male panel opposed female succession on the grounds it would divide Japan and destabilize the monarchy. A senior government official described the issue as “too heavy to tackle at this stage.”

Crowds waving paper flags as the Japanese Emperor and his family greet them on the 2nd day of 2019. The last New Year greeting of Akihito, before his resignation in 2019. Photo by Michal Staniewski / Shutterstock.com.

How do they weigh this up against the 70-80 percent of Japanese citizens (based on NHK and Kyodo polls, respectively) who support the idea of an empress or emperor of the matrilineal line? Or the success of Japan’s former empresses and empresses regnant? Or that female rulers have proven successful in other parts of the world. Just look at Queen Elizabeth II who has enjoyed almost seven decades of popular rule while trust in Great Britain’s institutions has otherwise crumbled.

Laughable Solutions

Solutions were discussed by the panel, though one wonders why it took several meetings and 21 alternating members. One solution, which is really just a half-baked appeasement, is to allow female royals to remain in the family after marriage as an assistant to the emperor. Furthermore, in the event that no male heirs of the Taisho bloodline remain, a suitable one may be poached from one of 11 former imperial family branches that were ousted from the household in 1947. Given women outnumber men in the surviving royal family by around three to one, this is wildly circuitous.

The Mako-Komuro “scandal” is not immaterial in all this either. Traditionalists are brandishing it as a cautionary tale to prove why women aren’t fit for the Chrysanthemum Throne. While a stress-related disorder that has continuously plagued current Empress Masako has been used to further the same cause. And in all that, ignoring the causes of the stress.

Japan’s Emperor Naruhito and Empress Masako on the vehicle at the royal parade to mark the enthronement of Emperor Naruhito. Photo by StreetVJ / Shutterstock.com

What’s All the Fuss?

All of this raises another pressing question: why do residents of developed democratic nations in the 21st century still give a toss about monarchies? Is there a subservience gene that’s been passed down hereditary lines after millennia of swearing fealty to deified kings? Do we deep-down long to be serfs presided over by absolute unwavering rule? Are we trying to clutch onto the last vestiges of tradition for fear of where monarch-less frontiers may lead us?

Perhaps the “monarchy as a symbol of the nation and its values” argument is the most convincing. But if that’s the case, it looks like Japan’s values are that women are better servants than rulers, who can only be trusted with a limited amount of responsibility. And that change, quite frankly, is a nuisance.

To put it more bluntly: Japan’s female royals are not royals at all. They are commoners-in-waiting. And the suggested solutions to Japan’s imperial succession conundrum have done little more than expose just how deep the problem goes.

Here are a few more frank op-eds about Japanese society to read:

Frankly: Nepotism is Built Into the Japanese Political System