There is a saying in Yakushima: “The gods will provide.”

I am not a religious man, but as I walked through the island’s picture-book forest, overhead branches reaching out like crooked wands casting enchantments on me with each footstep on the rain-slushed ground, green growing so profusely from every angle it felt eternal — as though the forest’s sole purpose was to be so endlessly and beguilingly green — I considered dropping to my knees and exalting whichever divine hand had guided me here.

This head-over-heels infatuation with Yakushima could probably be explained two-fold. Firstly, Japan is a busy place to travel; or it was, until Covid-19 prevented at least 30 million tourists from visiting the nation this year. In Yakushima, we were, as far as I could tell, two of the only outsiders on the island.

Secondly, finding this kind of beauty in Japan — an unfiltered, ever-changing landscape whose existence is the very embodiment of mono no aware; a place at ease with its own impermanence — is impossible. Or so I thought.

Mono no (ke) Aware

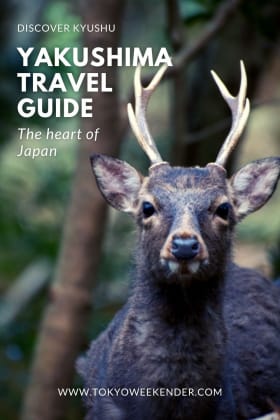

Yakushima, a dreary little sub-tropical island off the southern coast of Kyushu, is home to one of the world’s oldest primeval forests, which gained World Heritage status in 1993. Its local icons are the eponymous yakusugi cedar trees, wise evergreens with diameters of 10 meters-plus, heights double that, and roots dating back the Jomon Period (14,000–300 BCE).

Approximately five percent of all the world’s moss species also live in Yakushima, which is no surprise given there’s so much rain on the island it doesn’t appear to come and go so much as it’s permanently suspended in mid-air, ready to strike at any moment. This rain not only gives the moss, and therefore Yakushima, its vitality, it creates a constant soundscape wherever you go: drilling, pitter-pattering, ricocheting, spitting, plopping, but rarely ceasing.

“I considered dropping to my knees and exalting whichever divine hand had guided me here”

All of this rather enlivens the 600 individual moss species, who reproduce with quite some fecundity, creating a natural order that is the opposite: disorder. Moss — the lifeblood of the forest — usurps every surface it can latch on to; every branch, tendril, vine and rock bears a furry green coating just biding its time to reproduce further. The result is a uniquely biodiverse landmass of chaos and beauty intertwined, where trees grow upon trees which grow upon trees.

The Edge of the World

On our first day in Yakushima, as we drove along the coastal road, my eyes were fixed upon everything but the asphalt I was swerving drunkenly along: gaping at a rolling fog which spilled over the central mountains like dry ice; pointing out extra-terrestrial ferns wrestling for forest real estate; catching sight of clouds and sea, both gunmetal grey, battling on the distant horizon.

On a whim, I decided to take a detour through some swampy rice paddies — protestations from the passenger seat notwithstanding. Though one is well aware a coastline exists on Yakushima, it’s often hidden by roadside overgrowth. I was set on finding what lay beyond.

After skittering down an approximately 90-degree gravel track, conducting a hasty yet intense resiliency test on the little Nissan’s wheezing suspension, palm fronds slapping the windshield like a gunshot, we alighted upon a path overlooking a jagged volcanic landscape, matching the aggressive scenery of the sea.

Haggard and still partially vibrating from the descent, we left the car and traipsed along the inhospitable expanse of spiked black rocks, erupting from the earth like Godzilla’s spine. We looked southward over the Pacific. Towards what, we didn’t know. Okinawa? Palau? Papua New Guinea?

Maybe it’s because I, too, am from a dreary little island with a craggy, wind-whipped coastline, but standing there at the edge of the nation, in the midst of this monochrome portrait, I couldn’t help but feel as though I’d arrived home.

In Space and Time

The next day we made our way into the forest to hike the Shiratani Unsuikyo trail, famed as the location which inspired Princess Mononoke — though there’s scarcely a mention of Studio Ghibli’s 1997 film along the hiking path; rather, the forest is revered for what it has always been, not what it has become.

The several-hour hike climbed through a landscape that would have put Basho at a loss for words — tunneling under natural arches formed by ancient yakusugi trees and across rivers sluicing over monstrous slabs of granite — toward a rock at the summit, called the Taiko-iwa (taiko drum).

We ascended a set of battered steps flanked by knotted vines and the cracked remains of camelia fruit to reach the trail’s end. As we clambered onto the Taiko-iwa’s bulbous back, rain pelleting us from every direction, the clouds slowly parted to reveal the forest valley below. It was ablaze in jostling shades of green, bisected by the Anbo River charging with gusto along its upper reaches.

There was a profound sense I was surveying a vast expanse of time as well as space. The temporal and the spatial had become one, or perhaps something new altogether. There seemed to be no one else around for miles… or was it years?

The Heart of Japan

Yakushima brought to mind another saying: “The heart of Japan is in the countryside”.

I often hear this trumpeted as an old maxim. Maybe it was true once, but today Japan’s countryside is largely an extension of the concrete morass which blankets her cities. Beauty in rural Japan, rather being pure and untamed, is often the eventual – albeit brief – alleviation of industrial ugliness.

“The temporal and the spatial had become one, or perhaps something new altogether.”

For me the heart of Japan exists in moments. Moments when the past breathes perceptibly back into life. These moments are often fleeting: as soon as I realize I’m caught up in one, it scampers off like a grazing gazelle detecting a nearby predator. Yet their evanescent nature makes them no less cherishable; these moments keep the magic of Japan alive long after the novelty of living here departs.

Yakushima is one of the last bastions of old Japan; a living manifestation of her natural past. And that makes it a very special place indeed.

All in-text images by David McElhinney. Featured image: Shutterstock

For other inspiring places to visit in Kyushu see:

- Find Japan’s Most Beautiful Beaches on Kyushu’s Amami Islands

- Seven Stars in Kyushu Cruise Train: The Most Elegant Way to Discover Kyushu

- Kirishima Shuzo: The Kyushu Distillery in Miyazaki That’s Been Making Shochu Since 1916

- Japan Travel: Explore Northwestern Kyushu in Three Easy Stops – Fukuoka, Saga and Nagasaki

- Kyushu Weekender 2020 Guidebook

- Mystical Kirishima: A Guide to One of Southern Kyushu’s Wondrous National Parks

- Unzen Onsen: This Could be Heaven or This Could be Hell