There’s a difference between the kind of photographer who simply captures pretty images and the kind who spends months, even years, concentrating on peeling back the layers of a subject to expose its soul. British-born Adam Isfendiyar is without question the latter. He wants his photos to tell a real story. But more than that, he wants them to feel complete, so that he – and the viewer – walks away without a sense of something missing.

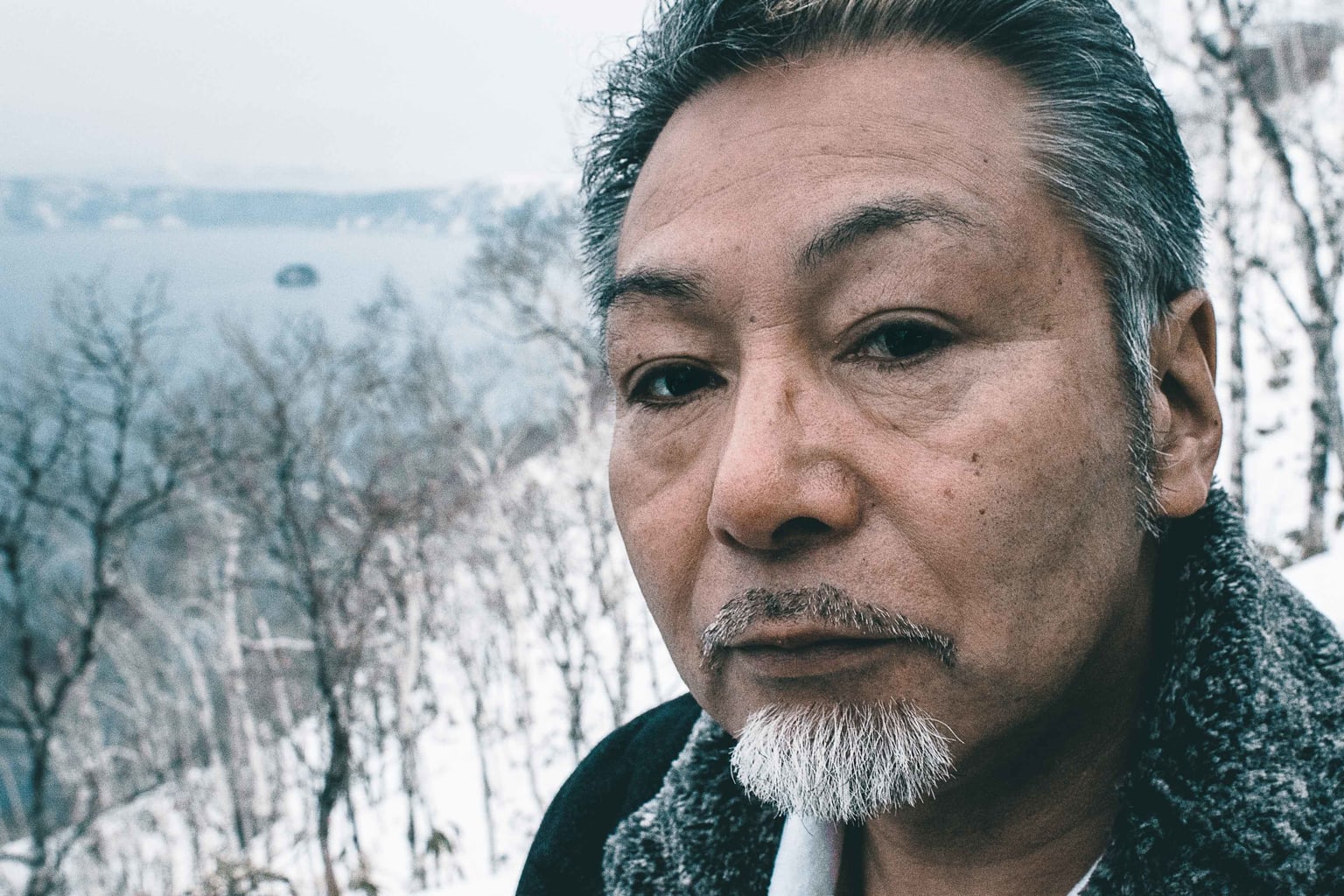

In creating his “Master – An Ainu Story” series, he spent just over two years traveling between Tokyo and Hokkaido to explore and document life within the Ainu community. The Ainu (which means “human”) are thought to be descendants from the Jomon people and originally controlled what is now known as Hokkaido. But after the Japanese government implemented an assimilation policy during the Meiji Period, the Ainu suffered marginalization and discrimination, with their entire culture reaching the brink of extinction. Over the last two decades, however, the Japanese government has begun to take steps to preserve the Ainu culture, with the latest progress being made in February this year when a bill that recognizes the Ainu as “an indigenous people of Japan” was approved.

Motivated by a desire to learn more about indigenous cultures and languages, Isfendiyar befriended and lived with an Ainu family in Hokkaido for several days at a time between 2016 and 2018. In his own words, he became part of the family, learning not only about their modern existence, but also about whether there’s sadness in the community regarding the loss of their culture, and what it was like for their ancestors when, in the late 1800s, they were forced to reject their identity.

How did you end up being invited to stay with an Ainu family?

I started the project with the aim of finding out more about Ainu people. I knew there were descendants of Ainu but I had no idea if there were still communities or where to find them. I went to the Ainu Culture Center in Tokyo and they told me about a festival happening in Toyama. While at the festival, I happened to get on the same bus as some of the Ainu performers, and ended up going to karaoke with them. After returning to Tokyo I reached out to them, asking if I could visit during the summer. I didn’t get much of a positive response and the very last person I contacted, a man named Kenji Matsuda, told me he would be very busy then because he runs a ramen shop. To be honest, at that point I actually thought maybe I shouldn’t bother with this project. But I sent him a reply and said, “Well if you’re busy I can help you out.” He replied, “Well if you help me out, you can stay at my place.”

And what was that like?

It was August 2016 and I spent about five days with him in the Ainu village near Lake Akan. He has a ramen shop there. I helped out in the restaurant, as I said I would. I washed dishes, served customers. I slept in the mahjong room on the top floor – the middle floor is the living room and the bottom floor is the restaurant. He took me to a family grave for Obon, and to meet some of his family in Kushiro, which is where he grew up. I didn’t take many photos the first time I went. But I asked him if he wouldn’t mind me coming back and doing a photo project. He said yes and told me I didn’t need to work for him the next time. [Laughs] I actually decided to carry on working for him, though, which I think helped me to feel like I was giving something back.

I returned in December for 10 days. I spent New Year’s Eve with his family, and that’s when I started taking more photos. The fourth time I went was for the Marimo Festival in October 2017. That was a good opportunity to take photos of people at the festival and in traditional dress. It’s the biggest gathering of people from different Ainu groups. By then I was starting to feel more of a connection with the place and the people. The more I visited, the more open and friendly people became. It started to feel like a home from home.

How did you want to set your photos apart from existing images of Ainu people?

I found that a lot of photography I had seen of the Ainu had a feeling of nostalgia for the past and gave the impression that it’s an old, dead culture. For me, it didn’t represent something that is still alive. This is just my interpretation of the photos; it may not have been their intention. But I wanted to do something a bit more modern looking, that gives the impression of something that’s still alive rather than something that’s a relic of the past. Also, the story I wanted to tell was the story of Matsuda-san’s life intertwined with the history of the Ainu. So my exhibition is split into two sections, the first being about Ainu culture and the second being about Matsuda-san’s life.

Why do you think it’s important to keep going back or to spend so much time on a project like this?

For the first couple of trips a lot of it is getting to know people and looking for the story. After having a bit of time and space, it’s easier to feel clearer about what you actually want to achieve. Towards the end, I had about 100 photos I was happy with. But I still felt like something was missing. There were gaps in the story. So I went back for one final time and it made all the difference. In the section of my exhibition that’s about Matsuda-san’s life, probably about half of the photos were from that last three-day trip. Because I had kind of had that a-ha moment of “Okay, I know what I want to get now.”

Do you think Matsuda-san enjoyed the process?

I felt like he enjoyed having the photos taken but at the same time he didn’t seem too bothered about what I was doing with the photos, or the exhibition. I felt like maybe for him it was more about our personal relationship. He told me that when we met he felt it was fate, like we’d met before, and that’s why he wanted to meet me again. When I served people at the restaurant, he would introduce me as his son. He would joke about it and tell customers that he used to live in England and met a woman there … basically made up this elaborate story. So I ended up calling him dad. [Laughs]

Did you feel a sense of sadness from the people you met regarding the loss of their culture?

I don’t think there’s sadness. There might be a certain amount of anger towards what happened in the past and perhaps how people have been discriminated against and treated, but I don’t know if it’s about a loss of the culture. I think it’s more about how they’ve been treated as people, maybe looked down upon and being seen as second-class citizens in Japan.

Tell us about Matsuda’s personal history and his feelings about preserving his culture.

Matsuda-san’s grandmother was born in the Meiji era in the early 1900s, so she lived through the time when Hokkaido got taken over and Ainu practices were banned. A lot of the things that were part of their daily lives were suddenly regarded as unlawful. So his grandmother’s generation tended to encourage their kids to not partake in Ainu culture and rather just assimilate and integrate into Japanese culture. This was difficult for the kids because they were being bullied at school for being Ainu, but at the same time they were being told at home to suppress their Ainu identity. So from both sides they were getting told there was something wrong with them. I think that has affected the community because many people of that generation tried to protect their kids by teaching them to assimilate rather than be proud of their culture.

“It was difficult for the kids because they were being bullied at school, but at the same time they were being told at home to suppress their identity”

For Matsuda-san, I think at first he felt it was a duty to protect the culture. When his dad died, he moved from Sapporo to Akan and took over his dad’s woodworking shop. And after his mom died, he felt he had to keep doing what his parents had been doing in Akan. To help keep Ainu culture alive. But over time it’s become something he now feels quite strongly about.

What kind of feedback have you had from Japanese people?

It seems like telling the personal story of someone who’s been directly affected by the Japanese assimilation policies of the Meiji era has been quite profound for some people. It’s not just hearing a third-hand story. It’s seeing the direct impact it had on a person. One Japanese person wrote an interesting comment in the guest signing book at my first exhibition at SOAS’s Brunei Gallery [in December 2018]. He said that, as a non-Japanese, I am possibly in a better position to understand the Ainu than Japanese people because the Japanese already have preconceptions from growing up in Japan. And issues between the Japanese and the Ainu may mean that the Japanese can’t get as close to the story as I could.

Having said that, there are a lot of Japanese people within the Ainu community who are getting involved in helping to promote and preserve Ainu culture.

Do you think the Ainu community feels more acceptance these days?

Yes, definitely. People in their late 30s and 40s are now tending to encourage their children to get involved in cultural activities such as the traditional dancing or woodworking classes. I think they’re around it more, it’s more out in the open, there’s more being done by the Japanese government – maybe this is partly also to encourage tourism but there’s definitely an acknowledgement of the Ainu culture now. A new national museum about Ainu culture is opening in Shiraoi in April 2020. And there’s even a university degree in Shiraoi specially for Ainu people where they can study the culture.

“Master – An Ainu Story” is showing in London from March 22 to April 10, 2019 at Sway Gallery in Old Street. Isfendiyar is currently looking for sponsors to help bring his exhibition to Japan. For more info or to contact him, go to www.adamisfendiyar.com

VISIT HOKKAIDO

JR Hokkaido Rail Pass — Unlimited 3 / 4 / 5 / 7 Day Pass

For an extra 5% off use our coupon code TOKYOWEEKENDER during check-out.