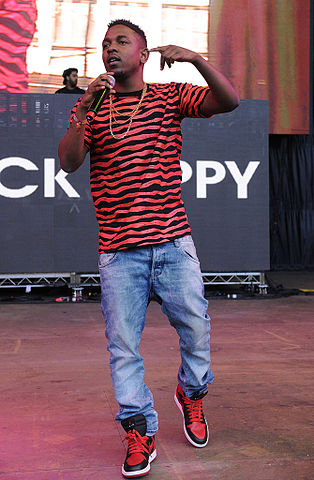

Rap music is rife with rags to riches tales, but none of those narratives are as nuanced as that of Kendrick Lamar. Awards have followed hype for the Los Angeles-based rapper because he subverts ghetto stereotypes, instead of glorifying them. He’s now enjoying a new outlet for his talents – festivals – and audiences in Japan will witness this first hand at Fuji Rock Festival, where he’ll open for rap vets Jurassic 5 on July 27.

For Kendrick Lamar, playing massive music festivals is so much more than a dream come true. The hotshot MC is known for his lyrical storytelling and imaginative album concepts, but his triumphant June 16 set at America’s gargantuan Bonnaroo fest, for instance, went beyond anything his mind had ever conceived.

“I’m from Compton, so I never really knew about festivals. There was like 60 thousand people out there at Bonnaroo, even though it was steamin’, pipin’ hot,” Lamar says, in a recent phone interview, of the blockbuster event that seemed all the more staggering for a young man hailing from one of L.A.’s most impoverished neighborhoods. “I wasn’t even aware so many people could come to an event at one time. I’m just learnin’ about that in the past three years. I never knew about that shit as a kid, so I couldn’t have even imagined that.”

“I wasn’t even aware so many people could come to an event at one time. I’m just learnin’ about that in the past three years. I never knew about that as a kid, so I couldn’t have even imagined that”

Compton was host to a smaller, but far more legendary, performance back when Lamar was a boy. One of his earliest memories is being hoisted from the cracked, scalding pavement and onto his father’s shoulders so that he could see over one particularly frenzied crowd. That throng had gathered around Dr. Dre and Tupac Shakur, as the local hip-hop heroes spat the verses of their mid-90s hit California Love for an on-location video shoot. It all happened only a few short months before Shakur was mowed down in a gang shooting, and then elevated to rap martyrdom.

“I remember a lot of people bein’ out there, a lot of kids just watching two legends performing,” Lamar says, his typically mellow monotone giving way to a timbre of lingering, near giddy awe as he describes Dre and Shakur’s street-side performance.

He goes on to add that seeing those rap titans in the flesh made his daydreams feel all the more tangible. “Ya know, when you’re a kid and you see people on TV all the time, it’s hard to imagine that they’re real people. So when they came around, I saw that anybody can do it, that anybody could get into hip-hop.”

Lamar did just that – hopping off his pop’s shoulders, listening to ‘Pac and Dre’s records religiously, and then penning rhymes of his own. By 2010, his freestyles and amateur YouTube videos created an online fervor that turned the heads of his hip-hop heroes. Before long, Dr. Dre was offering Lamar a lucrative contract on his Aftermath Music label, and praising the junior MC’s lyricism with public statements like this one:

“Kendrick writes about what he sees going on in his world. But unlike other emcees, he approaches his music with vulnerability, humility and expresses the truth about himself and his generation.”

With those rhymes, Lamar reflects his neighborhood’s gang culture more vividly than any of his Compton forefathers. N.W.A., the late-80s super group that Dre helped mastermind, was often accused of glorifying urban violence. But Lamar’s lyrics seem more like a cautionary tale – or at least a more realistic one.

The young rapper’s influences may have been apparent on early tracks like Keisha’s Song, a harrowing character study that detailed and derided the ghetto’s rampant sexual violence in the same vein as Shakur’s early-90s hit Brenda’s Got a Baby. The song may have been a standout from Lamar’s 2011 studio debut Section.80, but that album was also rife with Lamar’s own distinctive styles.

On the simmering cut The Spiteful Chant, he eschewed rap’s typical name dropping, denouncing nepotism instead: “Everybody heard that I fuck with Dre and they wanna tell me I made it… If he gave me a handout, I’m a take his wrist and break it!”

On other standout tracks like A.D.H.D. he didn’t tout clubbing and celebratory drug binging – that tune’s narrative instead opens with Lamar dousing a friend in cold water because he’s “… trippin’ off that shit again.”

Critics and fans applauded Section.80’s subversion. But Lamar followed it up with a modern rap masterpiece. He dubbed that 2012 sophomore set good kid, m.A.A.d city. Several music mags gave it a perfect ranking, including premium rap publication XXL, which fawned over songs like The Art of Peer Pressure, before calling it: “a spacious, internal monologue – he (Lamar) highlights the rowdy behaviors he displays in front of his friends, while having an almost opposite sentiment inside his psyche.” That theme was further developed on the album’s midway cut, good kid, for which the reviewer wrote: “the first-two verses discuss the allure and fear administered by – quite ironically – gangs and police sirens that both flaunt colors red and blue.”

Most hip-hop fans were excited to see Dre mentor such a promising young rapper. Other MC’s say the collaboration signifies so much more.

The disc featured guest turns from star wordsmiths like Drake and, of course, the man who’s been guiding Lamar all along, Dr. Dre. Most hip-hop fans were excited to see Dre mentor such a promising young rapper. Other MCs say the collaboration signifies so much more. Talib Kweli, for instance, believes Lamar is heir apparent to L.A.’s rap legacy.

“I saw Kendrick do something I hadn’t seen in a long time,” Kweli recently said to me (in a separate interview for another publication) of seeing Lamar perform a sold out gig in L.A. two years ago, just after the young MC had signed on with Dr. Dre. Kweli (an acclaimed New York underground vet, who was once a white hot prodigy in his own right), added that it didn’t take long for Dre’s affiliates to take the stage and welcome their newest cohort.

“Snoop Dogg, Kurupt, The Game and Dre all went up and sang Kendrick’s praises. Game said ’I’m from Compton. This is the only rapper I’ll say that is better than me.’ And then all of them hugged Kendrick together, and he broke down on his knees and started crying while the crowd chanted his name. I remember turning to the people I was with and saying ‘you’re watching history right now. You’re watching the actual passing of the torch,’” Kweli says, before adding that that onstage kudos giving gave him an odd sense of déjà vu.

“On The Black Album, Jay-Z said ‘If skills sold, truth be told, I’d lyrically be Talib Kweli.’ All the accolades Kendrick’s been getting remind me of when Jay said my name on his song – at the time, it made me feel like I was doing all the right things,” Kweli, who invited Lamar to spit a guest verse on his latest LP Prisoner of Conscious, says. He adds that Lamar’s elders should be taking notes from good kid, m.A.A.d city. “I see a lot of what I love about hip hop in what Kendrick does on there. I love the fact that his album is a hip-hop opera. He’s super inspiring.”

Lamar says he was ecstatic to meet his hip-hop heroes – but becoming better acquainted with them was less glamorous, more practical, and all the more inspiring as a result.

“I’d ask Dre to tell me stories about 2Pac,” Lamar says. “All he’d talk about was ‘Pac being really hard working, how he’d just go to the studio every night and knock out all these tracks, by himself and with all these other MCs. Dre said he was impressed by how ‘Pac had all these crazy ideas, and how he constantly manifested them onto albums.”

Lamar says he aims to be just as prolific and collaborative as Sharkur in his mid 90’s heyday. The rookie rapper has already racked up an impressive number of guest verses—aside from being featured on Kweli’s latest release, he’s also contributed to songs by other vets like Lil Wayne and D-40, along with his fellow hip-hop up and comers like J. Cole and A$AP Rocky.

Lamar would like to take that collaborative spirit a step further, to other genres, and the feeling is mutual for musicians such as James Blake.

But he’d like to take that collaborative spirit a step further, to other genres. The feeling is mutual for musicians like James Blake, a beloved dubstep and electronica virtuoso who told me (in an interview that led up to his gigs at Studio Coast back in early June), that he’d not only like to work with Lamar, but also befriend him.

“If I’m going to collaborate with someone, then it’s nice to sort of hang out with them. If we get on then the music’s going to be good, and if we don’t get on I wouldn’t even start making music with them. It’s good to feel like you’re making a passable connection, not just an A&R connection, especially when it’s someone like the (The Wu-Tang Clan’s) RZA or Kendrick,” Blake says, adding that he has worked with the aforementioned MC and has high hopes to make time for the latter. “I’d love to work with Kendrick, but he’s such a busy guy. I’d really want to get to know him, because I love his music.”

Lamar is equally complimentary when asked about Blake, adding that he aims to pencil the British electronica king into his calendar once they both wrap up their current, seemingly endless world tours. Lamar goes on to say of Blake:

“He’s an incredible artist. I like his tone of voice, the abstractness of it. He makes such a sporadic sound with his beats, it drives the energy up and down. It has a lot of emotion. That’s what I can dig, and it’s the same level of emotion that I try to put on my albums.”

Sharing that emotionally tumultuous narrative may have made Lamar’s music successful beyond his wildest dreams. But the next chapter of his autobiography has an even more joyous plot twist – one that doesn’t occur in atypical rap video dance clubs, but instead at the home that Lamar grew up in.

“My family is what makes me feel most successful,” he says before elaborating on how he now lends a shoulder to his father, years after the elder Lamar hoisted him up to better see Dr. Dre. “I love giving my family things that most people were able to do, but that we wasn’t able to do. Gas money. Or grocery shopping, so that they don’t have to worry about food stamps every month. Simple stuff like that. Just the smallest things that you can probably imagine.”

Kendrick Lamar plays Fuji Rock’s White Stage at 8:40pm on Sat July 27.

Kyle Mullin is a roaming rock journalist who has contributed to music mags around the world. You can read his interviews with Iggy Pop, David Byrne and St. Vincent, Brian Wilson, Ai Weiwei and others at kylelawrence.wordpress.com. He spoke with Japandroids and James Blake for Tokyo Weekender in February and June this year.