Do you think there is any room for more digital cameras on the market? Every gift season, it seems, has a slew of new models each claiming advantages over its predecessors. Usually, this is demonstrated by an increase in the number of megapixels the camera can capture. Great; what is a pixel and how many do you need, anyway?

A pixel is simply a dot of color (a rectangle actually), and the number you need depends on how you will show your pictures and the clarity you require.

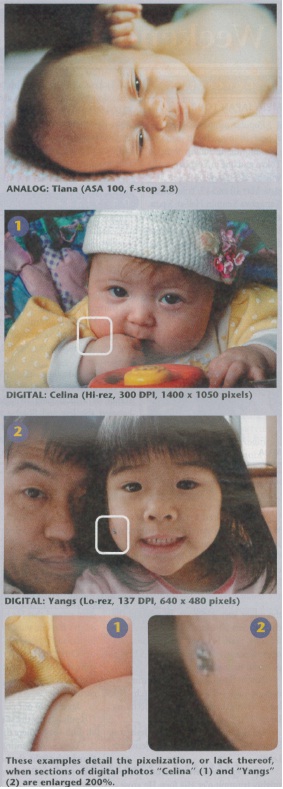

I shot the photo “Tiana” with my Nikon F800. The large aperture opening limits the area of focus to her eyes and allowed for a higher shutter speed 1/60. In terms of clarity, the photo is reasonably crisp. Compare that to the photo Dov shot of me above. Clearly, professional level equipment makes a difference and the photo is much more clear than what my camera is able to achieve. If you seek clarity at least on the level of the “Tiana” shot, then one thing you must have is lots of pixels.

PRINT: The printing world has been taking analog photos and making them digital for years. In fact nearly all of the photos in this publication (with the exception of Tiana and my photo on this page) can all be called digital photos. We take the original photos, scan them (digitize them) and use these digital files to print our publication. As a rule of thumb, the publishing world says that you need 300 DPI (dots per inch) to reproduce the photo with professional-level clarity. In this case the “dots” are pixels.

Using this rule of thumb, the number of pixels you need to print a photo at 4.667″ x 3.5″ (photo lab size) that is indistinguishable from a professional camera is 1.47 megapixels (1400 x 1050). That same picture, however, won’t be able to be enlarged. If you want to print a photo at 8″ x 6″ using the standard rule of thumb you will need a 4-megapixel camera.

In reality, 300 DPI is too strict, 250 or even 220 DPI will produce a fine photo virtually indistinguishable from all but the best photographic equipment. At 225 DPI, a 4-megapixel camera can be used to print photos up to 10″ x 8″. Some people claim that prints of 14″ x 11″ are acceptable (about 150 DPI), but upon close inspection, the pixelation is evident (see photo, Yangs (Lo-rez, 137 DPI, 640 x 480) at right). On the other hand, 35mm negatives that are enlarged to 14″x 11″ lose crispness, too.

Digital camera resolutions are measured by the total number of pixels (dots) they can capture. A 4-megapixel camera at its highest resolution captures pixels at the rate of 2400 x 1800 pixels (4,320,000 total pixels). So if you want to print your own photos and enlarge some of them, you will want to have a high resolution camera and shoot at the highest resolution possible. You can always delete pixels, but you can never add them

SCREEN: Any photo that you view on a screen (computer, television, etc.), uses a resolution of 72 DPI. If you are using your camera to create photos for web sites, e-mail or television slide shows you may not need a high resolution camera. After all, a camera with a resolution of 2400 x 1800 will produce a photo with the physical dimensions of about 33″ x 25″at 72 DPI! That requires a lot of scrolling.

Incidentally, because digital cameras are essentially video cameras (screen-based), they always capture pixels at a resolution of 72 DPI. Raising the DPI is just a matter of shrinking the photo. The number of pixels is constant That is why the resolution is measured in terms of pixels, not DPI.

The reason you would want a megapixel camera for screen work is for flexibility and, again, clarity. You may only want to send a small 4.6″ x 3.5″ (84,672 pixels) image to your folks via e-mail, but the ability to choose those pixels is important. Having lots of pixels at the beginning ensures the picture’s greatest detail and most subtle coloring. Then, it is easy to use software to reduce the number of pixels for easy screen reproduction and small file transfers.

THE PHOTOS: The photos at left were all shot in the same type of situation—using a large window as the only light source. “Celina” was taken with the digital camera set to mimic an ASA of 125 and a 2.8 f-stop; so it is very easy to compare depth of field, shadow detail, saturation and clarity with its analog counterpart. I did no additional retouching of the digital photos, which would have resulted in at least a crisper shot.

Digital photography has come a long way. There still remain areas of difference between the two mediums, but these days, it can no longer be said that digital photography does not match its analog counterpart in terms of printed photographs.