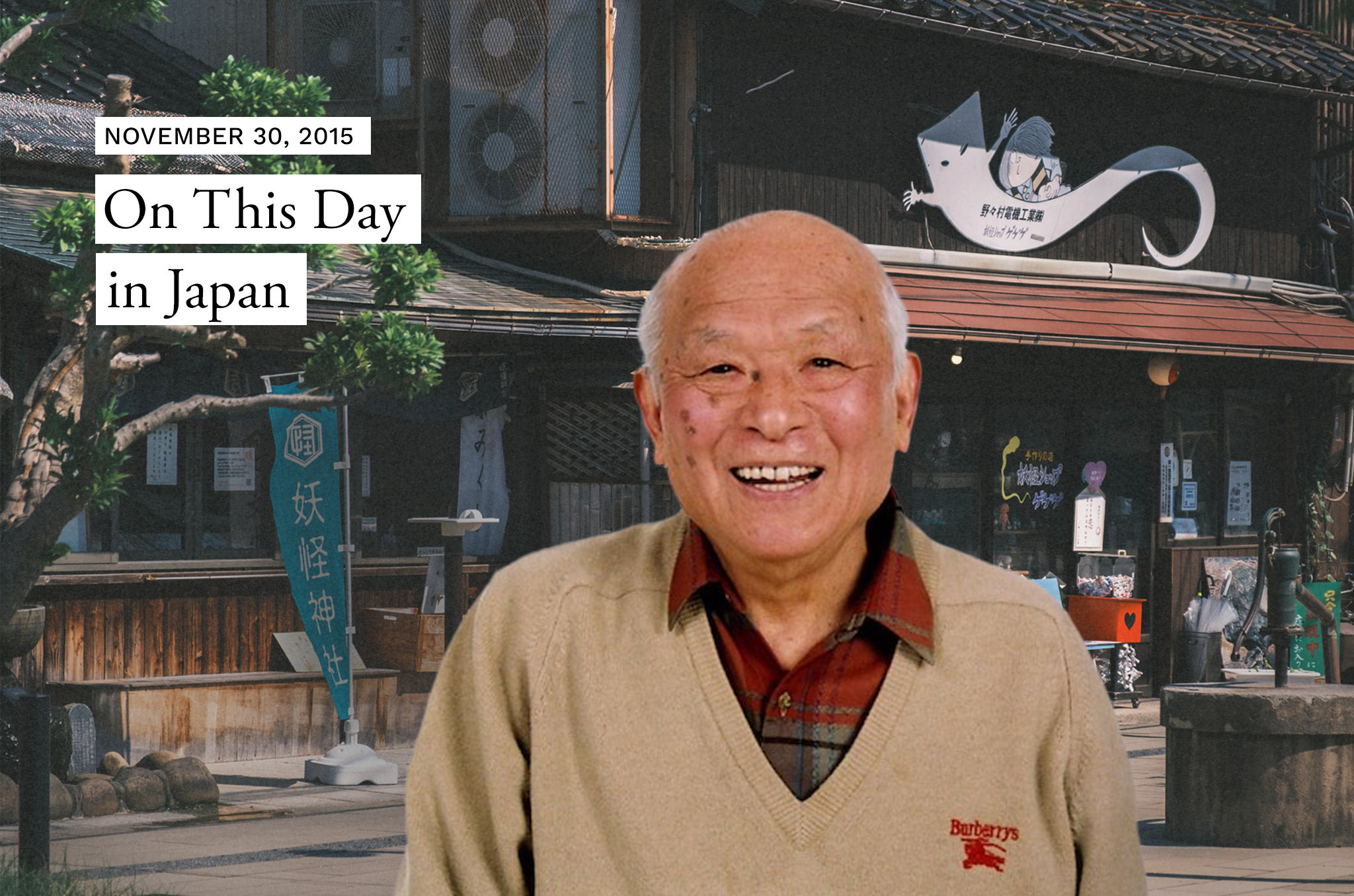

On this day 10 years ago, Japan lost one of its most beloved manga artists. Shigeru Mizuki, who in 2025 was posthumously inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Awards Hall of Fame, is best remembered for reviving interest in yokai — supernatural creatures from Japanese folklore — which he often used to depict the horrors of war. His most well-known manga was GeGeGe no Kitaro, a series about a one-eyed boy ghost. For our latest Spotlight article, we are taking a look back at the life and times of the mangaka legend.

Mizuki aged 3 (left) and 18 (right) | Wikimedia

The Early Life of Shigeru Mizuki

Born Shigeru Mura in Osaka on March 8, 1922, Mizuki grew up in the coastal city of Sakaiminato, Tottori Prefecture. As a toddler, he mispronounced his name, Shigeru, as “Gegeru,” leading to the nickname “Gege” that was later used as the inspiration for his most famous manga. From a young age, he showed an aptitude for illustration and became fascinated by regional monsters he learned about from Fusa Kageyama, an old woman who sometimes worked at his home and shared ghost tales with him. He called her NonNonBa.

He was also known as a brawler who led a children’s gang. “On his first day of elementary school, he looked for the toughest-looking kid in his class and beat him up to make sure everybody understood who was the boss,” his daughter Naoko Haraguchi told Zoom Japan. “He was big and strong and quickly became the leader of a gang of similar troublesome children. They often fought with other gangs to gain control of the area. They thought nothing of using sticks and throwing stones, and he often came home covered in blood.”

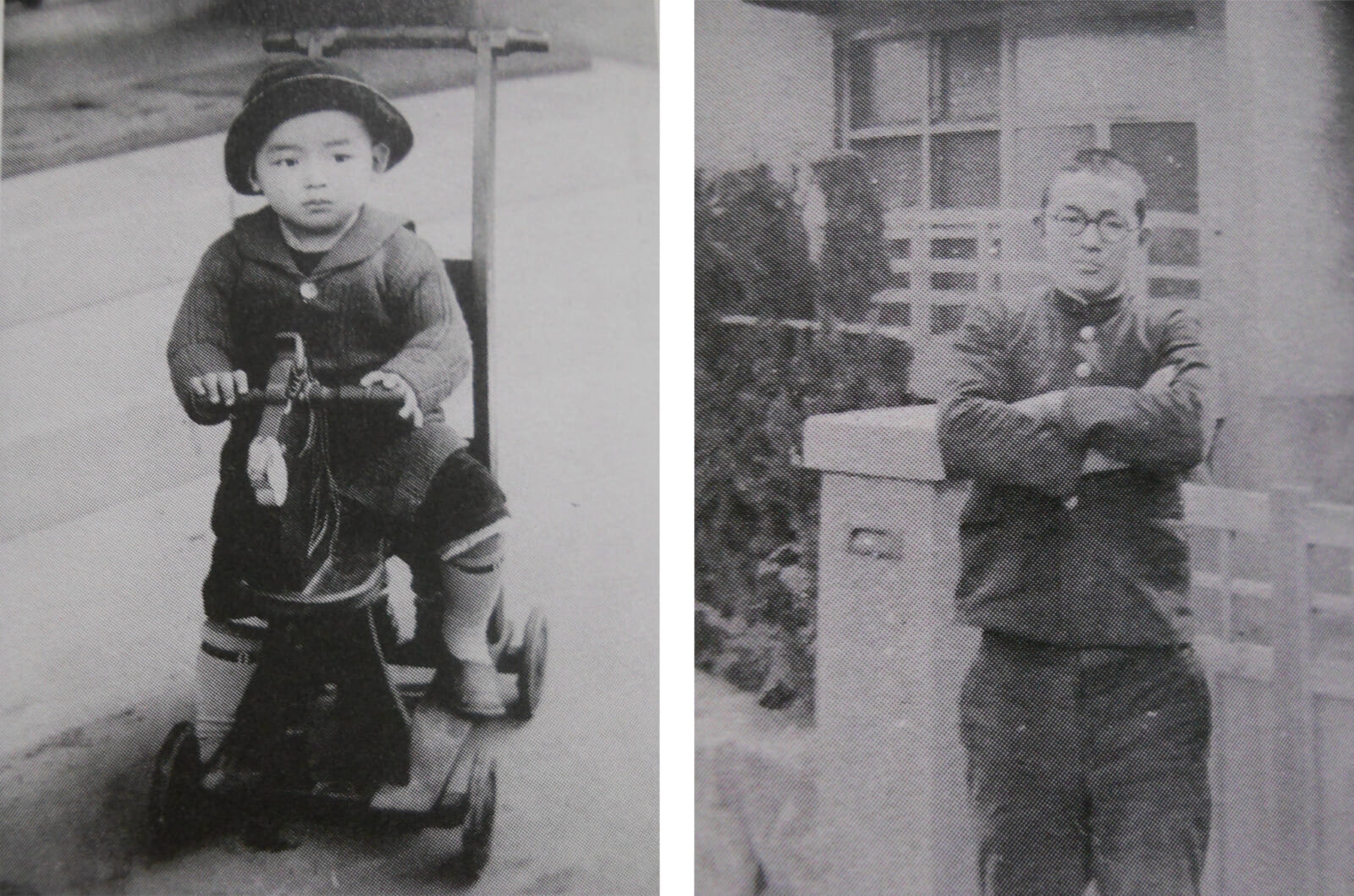

Mizuki (right) with his father, taken 1943 | Wikimedia

The Horrors of War

In 1942, Mizuki, aged 21 at the time, was drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army. Initially assigned to a bugle corps, he soon requested a transfer. Sent to Rabaul, a city on New Britain Island — now part of Papua New Guinea — he had a profoundly traumatic wartime experience. He lost many of his comrades due to bombs and disease, while some others chose to take their own lives. Mizuki himself was on the brink of death after contracting malaria. Despite doctors recommending stopping his food and medicine because his chances of survival appeared to have gone, he made a miraculous recovery.

While recuperating in hospital, however, Mizuki was struck by a bomb and lost his arm. Speaking to The Japan Times in 2005 about the incident, he said, “The moment I was hit, the pain was so fierce that I shrieked — but then the next moment, I forgot everything. People say that, when you are bombed, time becomes frozen, and the place turns into a vacuum. Your memory is temporarily lost, and you go into a different world when the bombing takes place right by you.”

Relationship With the Tolai People

After losing his arm, Mizuki befriended the local Tolai people, communicating with them using a Pidgin language. Unlike other soldiers, he treated them with respect and, as a result, they welcomed him into their community. They reportedly offered him food and helped restore his health in exchange for army goods, such as cigarettes and blankets. One Tolai person he developed a particularly close bond with was a man named Topetoro. Mizuki later honored their friendship with the comic Fifty Years With Topetoro, released in 1995.

According to Mizuki, he was offered a farm, a house and even a bride during his time in Papua New Guinea. He seriously considered staying there after the war, but a military doctor persuaded him to return to Japan to face his parents first. The Occupation in his homeland ended any thoughts about going back to Papua New Guinea soon after the war. However, he did return for a visit more than a quarter of a century later, when he was reunited with Topetoro and others who made him welcome during the conflict. In 2003, the people of New Guinea honored Mizuki’s long relationship with the Tolai by naming a road after him in Rabaul.

An illustration from Mizuki’s version of the Kitaro kamishibai play | Lost Media Wiki

The Birth of Kitaro

Back in Japan, Mizuki did several odd jobs, such as selling fish and driving pedicabs. He later worked as a landlord at Mizuki Manor, the inspiration for his pen name. One of his tenants there introduced him to the world of kamishibai — a traditional form of Japanese street theater using picture cards — and Mizuki began producing illustrations for the medium. In 1954, he was asked by his boss to create some stories based on Kitaro of the Graveyard, a 1930s kamishibai written by Masami Ito about the supernatural adventures of a one-eyed yokai.

With televisions on the rise in Japan and the kamishibai industry on the decline, Mizuki decided to try his hand as a kashihon (rental manga) creator, releasing his debut work, Rocketman, in 1957. Three years later, Kitaro of the Graveyard was published as a series of rental books before eventually being serialized in Weekly Shonen Magazine. It was renamed GeGeGe no Kitaro in 1967 because sponsors for the prospective anime series were concerned about the negative implications of having “graveyard” in the title. The tone of the series was also intentionally adjusted to be less dark and more action-oriented. Both the manga and anime series proved a massive and enduring success.

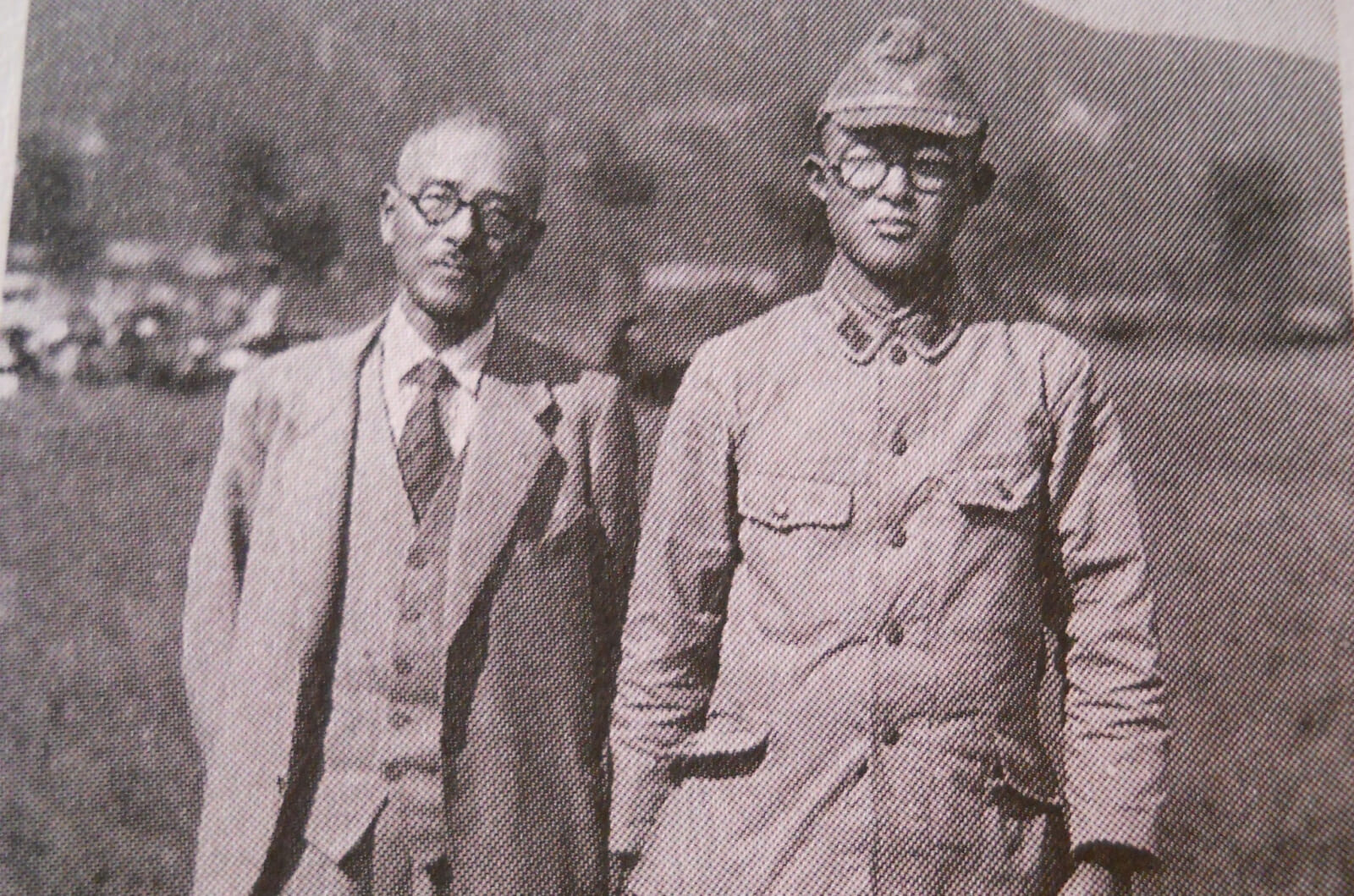

Cover and inside image of “Onward Towards our Noble Deaths” (2022 reissue) | Drawn & Quarterly Publications

War Stories

In 1971, a year after the original series of GeGeGe no Kitaro concluded, Mizuki released a critically acclaimed biographical manga about Adolf Hitler, telling the story from his early life in Austria to his downfall toward the end of World War II. Another war-related manga that was lauded by critics was Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths, which describes Mizuki’s experiences as a soldier in the New Guinea campaign. His comrades were instructed to die for their country to avoid the dishonor of survival. “No one is looking at me,” reflects one soldier facing death on the battlefield. “Nobody will remember my words … I’m just going to be forgotten …”

The war is also covered extensively in Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan, a manga series combining Mizuki’s personal experiences with historical events. Narrated by Nezumi Otoko, a half-human, half-yokai character from GeGeGe no Kitaro, it presents readers with a candid perspective on 20th-century Japanese history, particularly the buildup to, the conflict itself and the aftermath of World War II. It’s a powerful condemnation of a period in history that left a deep, unresolved legacy on its people. The message from Mizuki is clear: “Never forget the price that was paid for the world you live in now. Never forget the lessons of history.”

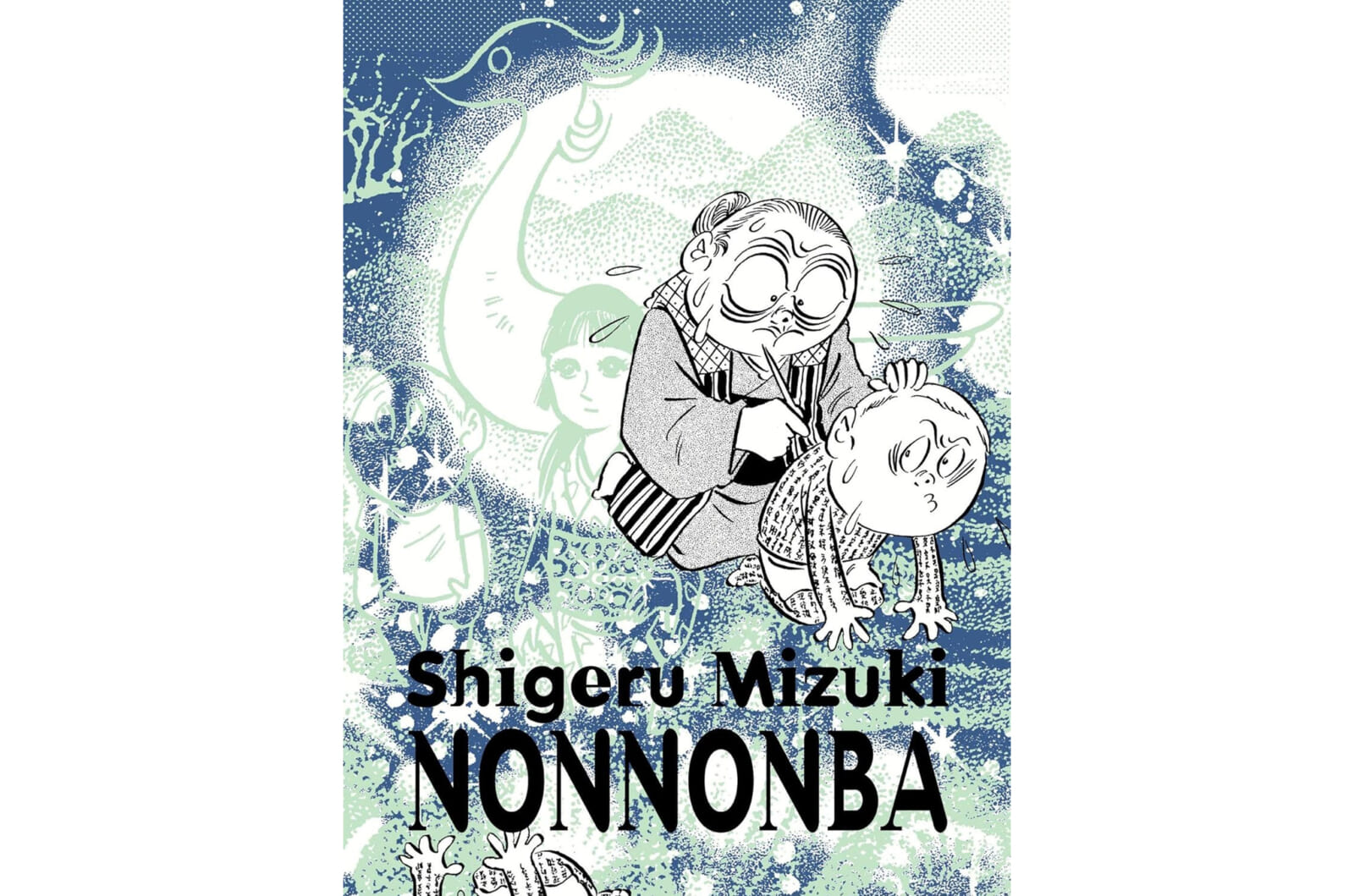

Cover of “Nonnonba” | Drawn & Quarterly Publications

International Success

In the 2010s, Mizuki’s popularity spread overseas thanks to many of his stories being translated, often by Jocelyne Allen, including Kitaro, Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths and NonNonBa, a charming memoir of Mizuki growing up in Japan and the grandmother-like figure who fed him stories of yokai. NonNonBa was the first manga to win the Fauve d’Or award for best comic book at the Angoulême International Comics Festival. It was one of several awards Mizuki picked up during his lifetime. Other notable honors included the Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize and the Person of Cultural Merit Award.

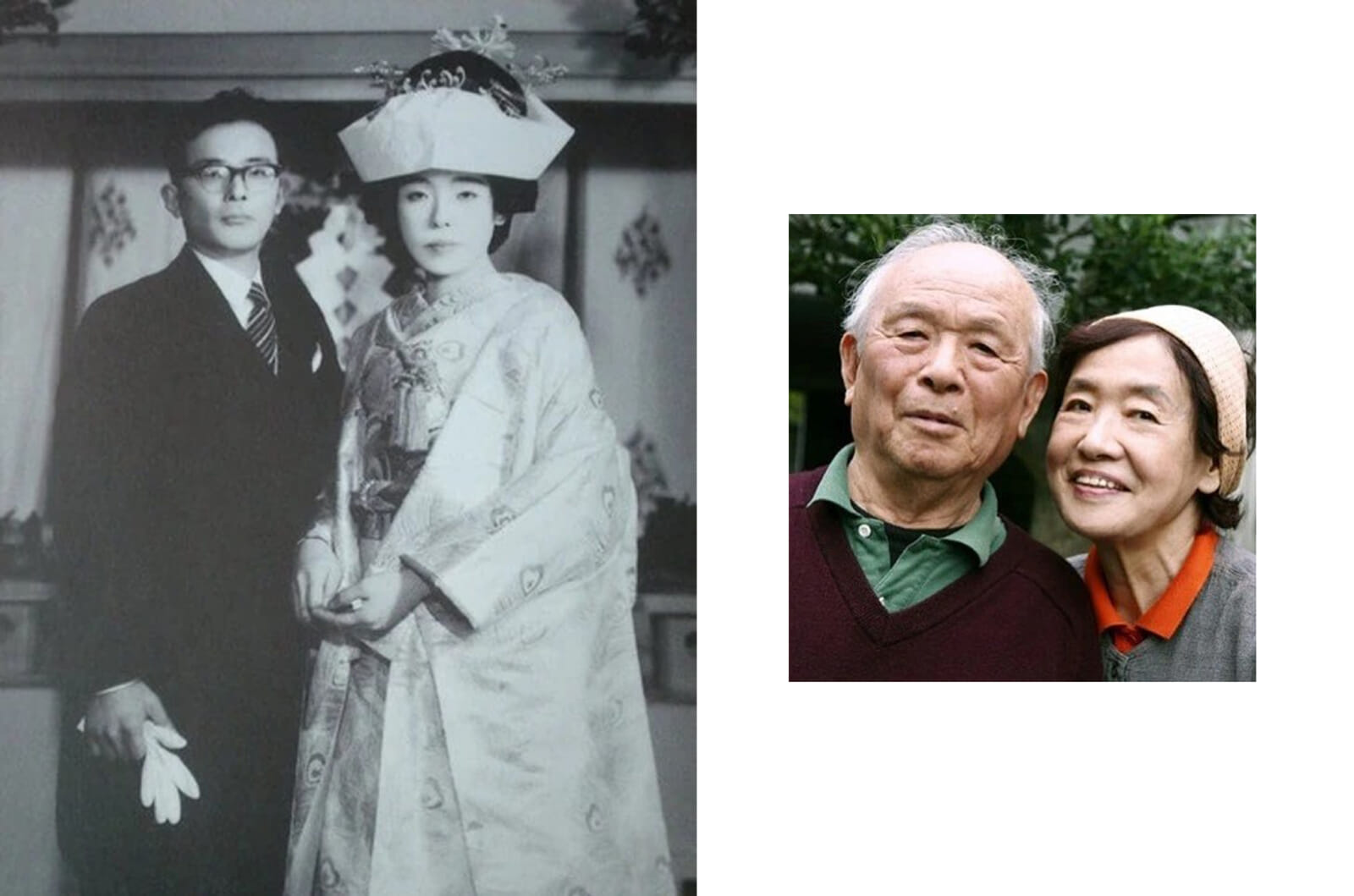

Mizuki’s biggest supporter throughout his career was his wife, Nunoe Mura. The pair tied the knot in 1961, having only met five days earlier. She managed the household through extreme poverty and later directly assisted her husband with his work. In 2008, she published The Wife of GeGeGe, detailing her life with Mizuki, particularly their financial struggles before he became successful. It sold over 500,000 copies and was adapted into an NHK asadora series starring Nao Matsushita and Osamu Mukai in 2010.

Mizuki and wife Nunoe Mura’s wedding photo (left) and later in life (right) | GeGeGe no Kitaro Wiki

‘Being Alive at This Time Is the Only Thing Worse Than Death’

On November 30, 2015, Mura lost her life partner. Mizuki died of multiple organ failure at the age of 93. He had undergone emergency surgery a few weeks prior following a fall at his home that resulted in a head injury. His daughter, Haraguchi, described him as a “workaholic at heart,” who “kept drawing and giving interviews almost until the very end.” She added, “He never succeeded in becoming lazy.” This was a reference to his “seven rules to be happy,” which included “Be lazy.” Shortly before his death, Haraguchi discovered notes written by Mizuki while going through some old papers in his office. “Reading it,” she said, “was like reading my father’s mind, as he screamed against his fate.”

The notebook was written in 1942, just before he was shipped off to fight in the war. “50–100,000 men are dying in this war every day,” he wrote. “Of what point are the arts? Of what point is religion? We aren’t even permitted to contemplate these things. To be a painter or a philosopher or a scholar of letters; all that is needed are laborers. This is an age painted with the earth tones of graveyards. An age of buried humanity, where people are just lumps under the earth. I sometimes think being alive at this time is the only thing worse than death.”