In the quiet stillness of his workshop, Kenta Watanabe crouches over a vat of liquid dye, gently submerging a handful of white threads into the inky well. As an impenetrable darkness subsumes the fabric, he gingerly massages its tendrils. His hands are stained a deep shade of indigo, and a faint blue cast remains even after the day’s work. It’s a sight at once unearthly yet strangely comforting — a physical trace of the pigment that has come to define his life.

As one of Japan’s last remaining aishi — indigo artisans who produce their own dye — Watanabe has dedicated his youth to sustaining the endangered pulse of aizome, a natural indigo dyeing technique with centuries of history. In her new documentary short, A Color I Named Blue, Emmy Award-winning filmmaker Sybilla Patrizia takes a close look at the intertwined journeys of Watanabe and Shinya Kato, who works alongside him.

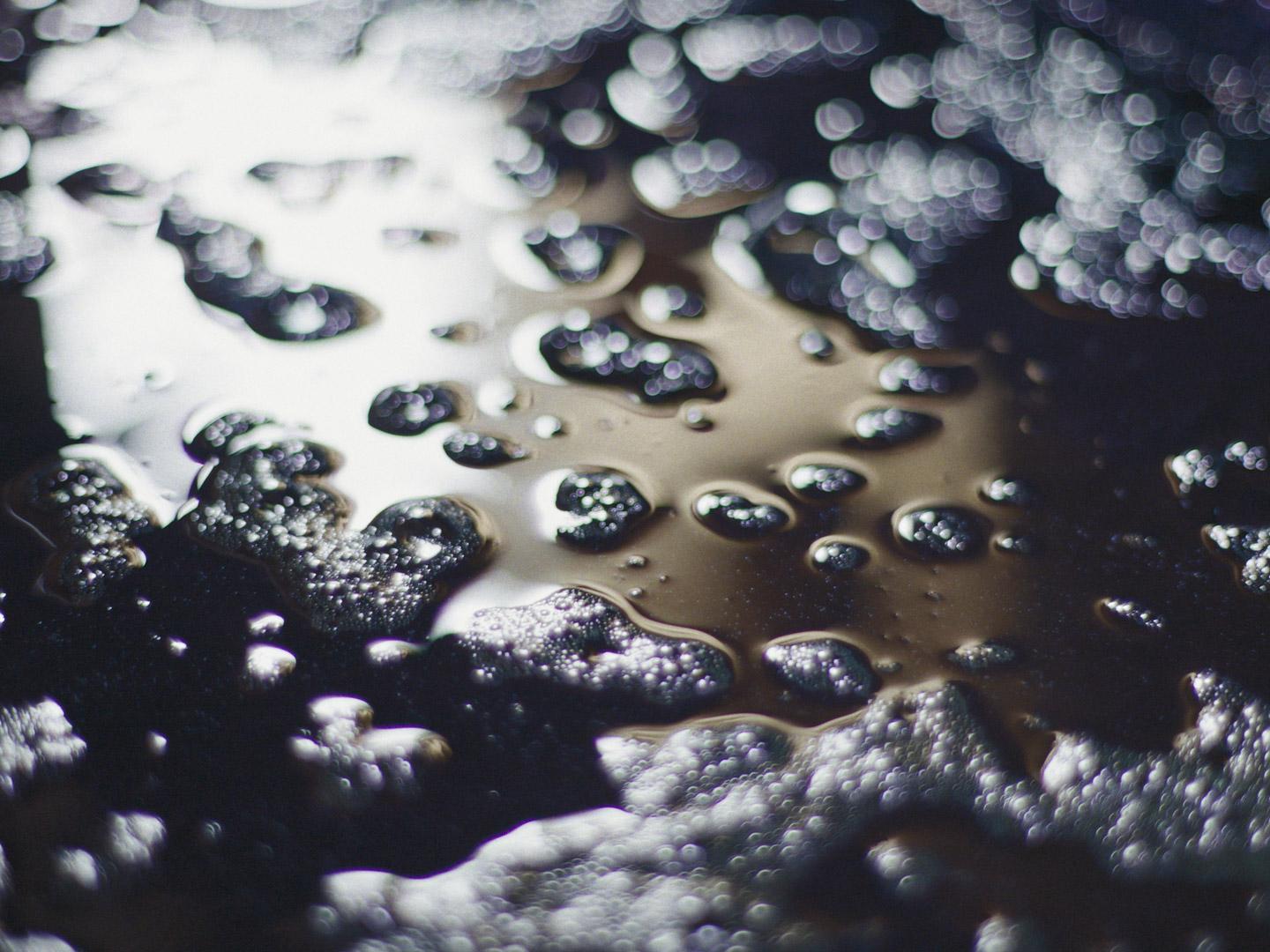

From breathtakingly intimate, richly textured glimpses of the dyeing process to sweeping views of the Japanese countryside, the documentary tells a story that’s both granular and expansive. It’s a meditation on a new generation of artisans safeguarding a generations-old craft, but also on the universal intricacies of perception — how we apprehend the world and transform it into meaning.

In Search of Indigo

Originally from Austria, Patrizia was drawn to Japanese art, design and architecture from a young age. “Japanese aesthetics really spoke to me because it was so opposite from what I was told was beautiful growing up,” Patrizia says, referencing the distinct presence of ma (negative space) in traditional woodblock prints and ikebana flower arrangements.

As a filmmaker, she often turns her lens toward Japanese culture and society; she’s tackled a wide variety of subjects, ranging from the dark side of the manga industry to the finely honed process of creating bonito flakes. When she came across videos of indigo dyeing online, she was struck by the dye’s lasting imprint on the skin. “I saw that the indigo dyers had blue hands and blue arms,” she remembers. “The blue doesn’t just wash off. [The artisans] carry it into their everyday lives — their bodies are immersed into their craft.”

Further research brought her to Watanabe and Kato, some of the precious few aishi still actively practicing the art from their workshop in Kamiita, Tokushima. Unlike many practitioners of traditional Japanese craft, who inherit their profession from family members, both men approached indigo dyeing from an outside perspective.

Watanabe first discovered the art at a workshop in Tokyo. In the documentary, he recalls the transformative encounter: “I was struck by the indescribable scent of fermenting indigo, the sensation of dipping my bare hands in the liquid,” he muses. “[The color] wasn’t just two-dimensional, but so deep that it felt like I would get pulled into it.”

Guardians of a Living Blue

Consumed by this moment of sublimity, Watanabe abruptly quit his job and relocated to Tokushima to learn the ins and outs of the craft, but he quickly realized that there were only a handful of artisans left continuing the original method of producing indigo dye from scratch.

Traditionally, the year-long process involves cultivating tadeai, the Japanese indigo plant, then fermenting its leaves for three months to form sukumo, the base material for liquid dye. After a period of rest, natural wood ash, sake and wheat bran are added to the sukumo to prompt deoxidation and activate the dye’s microorganisms. This technique, called lye fermentation, results in the natural dye’s longevity and understated yet potent shade — one that cannot be replicated with chemicals.

The labor of love has historically involved two groups of experts: those who tended to the plants and prepared the living vat of color, and those who dyed the fabric threads. Breaking with tradition, Watanabe set out to master both sides of the operation, feeling that a new, merged system was necessary to sustain the craft in its full, authentic form.

“Most people, when they think about indigo, are drawn to its beauty,” Patrizia says. For artisans, it’s different. “For them, it’s less about the simple beauty of the outcome; it’s about understanding the process necessary to reach this outcome.”

Likewise, for Patrizia, understanding the evolution and symbolic significance of color in Japanese culture was essential to faithfully capturing the spirit of aizome. “In the past, common people in Japan were forbidden from wearing colors; they were only allowed to wear grays, browns and indigo blue,” she says. “So indigo blue became a color of the common people.” The shade came to be known as “Japan Blue” among foreigners in the late Edo period.

“Fast-forward a few hundred years; you don’t see indigo blue almost anywhere anymore because we have so many different chemical-made colors,” Patrizia continues. “As times change and cultures shift, certain colors become more or less important.”

Shades of Ambiguity

What hasn’t changed, though, is the Japanese people’s rich, highly personal relationship with color. In the documentary, Watanabe discusses the country’s penchant for poeticizing everyday impressions, referencing the palest shade of indigo, named “peeking into a jar” — kamenozoki. “After opening their pot of water in the morning, [our ancestors] would see the reflection of the sky on the water’s surface and named it after that. In other words, they would name colors after scenery or emotions,” he explains.

Kato, who is partially colorblind, intimately grasps the inherent subjectivity in how we perceive color — an interplay between emotion, memory and even cultural background. The same twilight sky, for instance, can feel inexplicably menacing to some and wondrously romantic to others; the vibrant blue of a childhood beach vacation may no longer exist outside your mind. This ambiguity is precisely what endears Kato to his medium. While the aishi’s job is to formulate color, he proposes, “ultimately, color is created in the head of the person who sees it.”

As if bringing his argument to life, Patrizia suffuses the film with a quietly overwhelming spectrum of blues. It’s one thing to consider what a color means intellectually and another to see just how much is contained within the simple descriptor of “blue”: the hazy cerulean of a mountain town at blue hour; the pale surface of a still pond mirroring the sky; the midnight obi of Awa Odori dancers at a summer festival.

Through these mesmerizing vignettes, Patrizia suggests that for Watanabe and Kato, the art of indigo is not just about studying a meticulous craft. It’s about preserving a long-held devotion to rendering the colors we cherish — both in nature and in the cultural ties that bind a community. This profound sense of humility, Patrizia believes, is a fundamental aspect of heritage crafts in Japan.

“There’s always this understanding that we’re just one small part of this world — this bigger system,” she suggests. “Even though this is a story about a tiny village and a seemingly tiny craft in Japan, I would love for viewers to see how all of us are connected and the same.”

*Images courtesy of Sybilla Patrizia / A Color I Named Blue

More Information

A Color I Named Blue is currently in the process of becoming a feature film. For updates, head to Patrizia’s official website or follow her on Instagram.