When I was growing up in the early 2000s, we expressed our identities through carefully selected knickknacks — dress-up dolls, trading cards, obscure band posters — and through allegiance to specific brands. Abercrombie & Fitch polos had a generation of preppies in its grip; everyone knew what it meant to shop at Hot Topic. Fast-forward two decades, and consumption-as-expression has reached astonishing new heights. We are collectively drowning in a sea of grinning Labubus — temporarily, of course, soon to be washed away by whatever microtrend is served up next on an algorithmic platter.

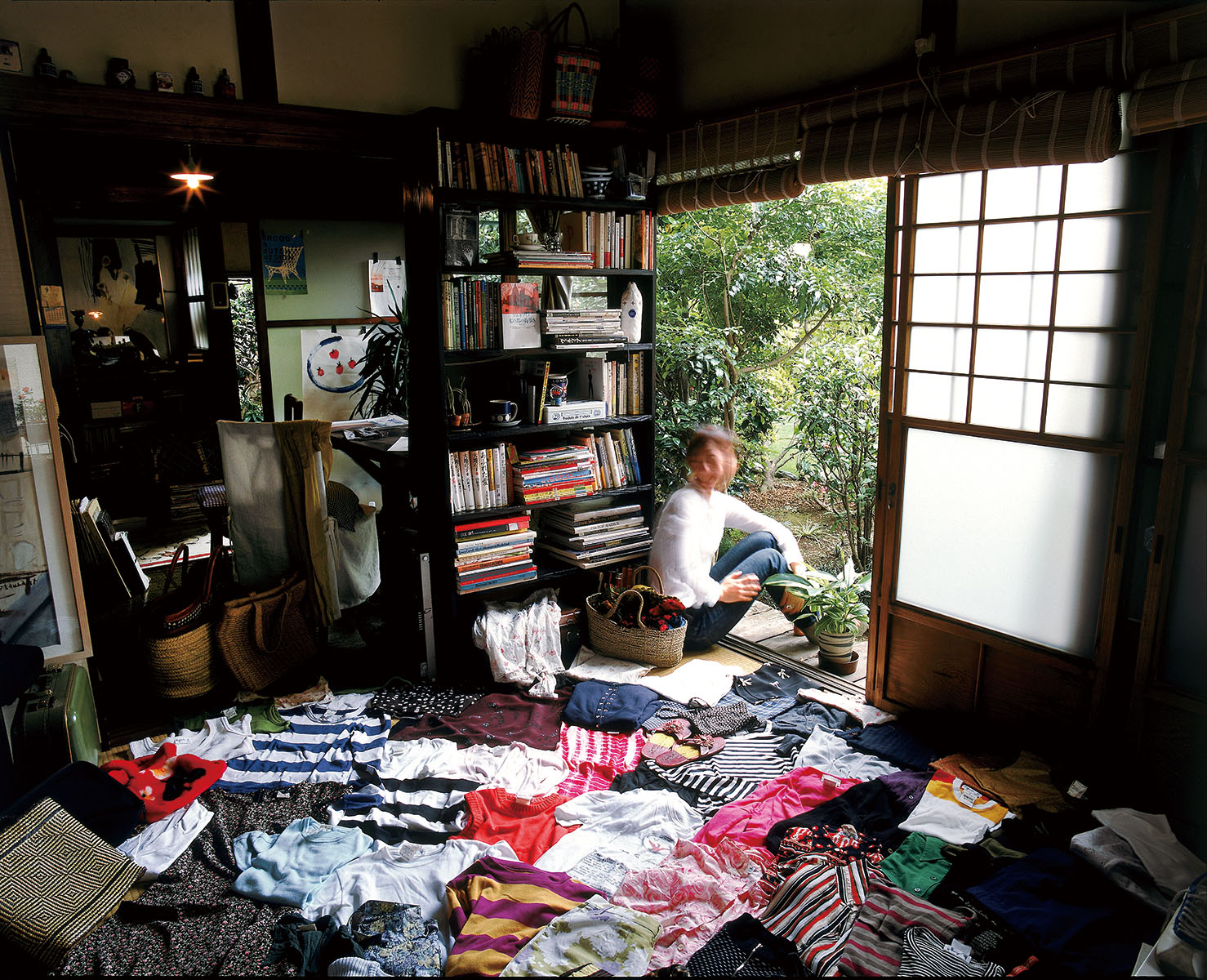

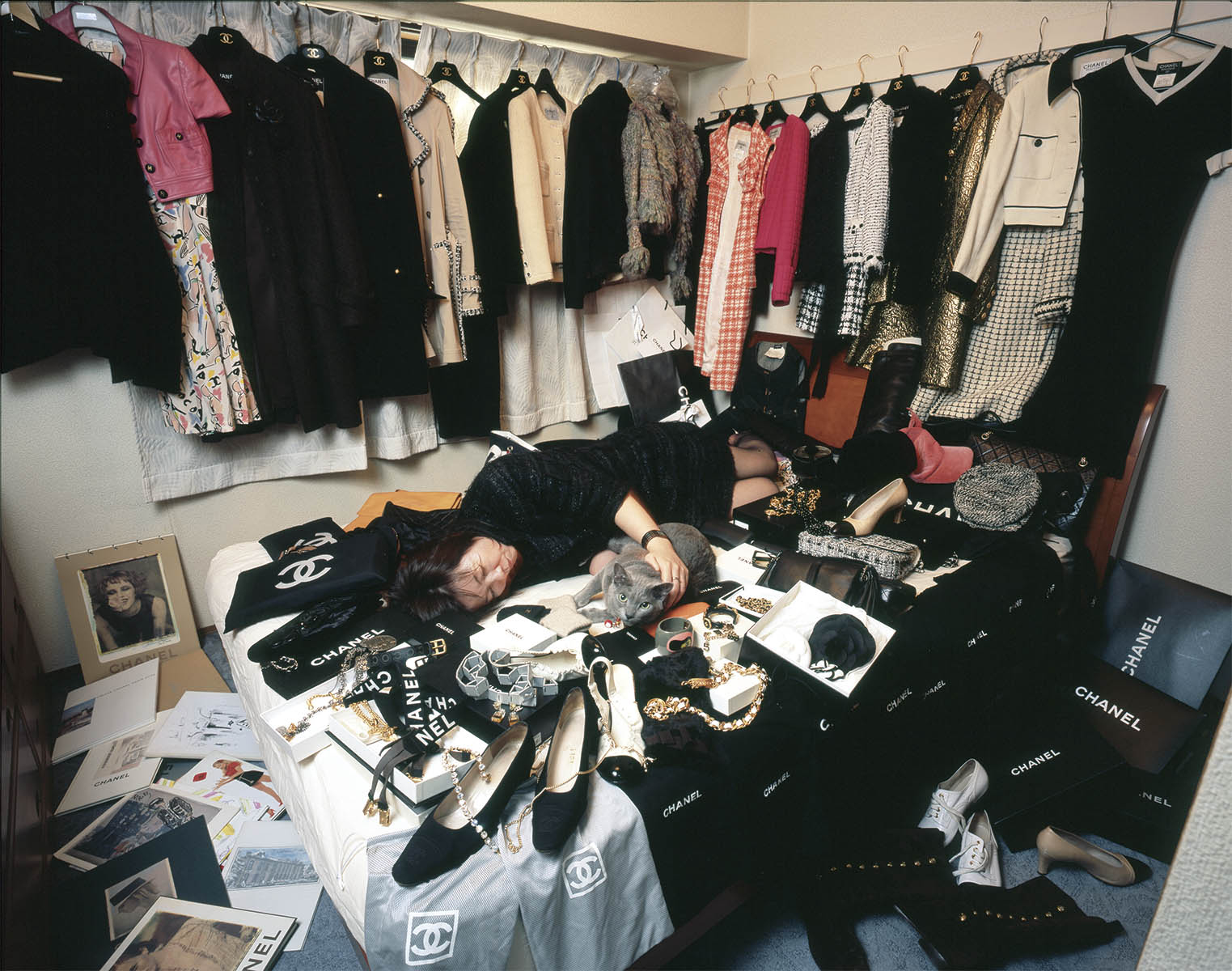

Happy Victims comes before all that. The cult classic photo series by celebrated Japanese photographer Kyoichi Tsuzuki originally appeared in the now-defunct fashion magazine Ryuko Tsushin between 1999 and 2006, and was immortalized in book form in 2008. The series depicts ordinary Tokyoites with extraordinary collections of revered fashion designers, colorfully draped over every nook and cranny of their cramped apartments.

This July, 17 years after its original publication, Barcelona-based publisher Apartamento reissued the legendary photo book, with an updated foreword by Tsuzuki and an introduction by Isabella Burley of Climax Books. Looking at these portraits now — at once documentarian and theatrical, claustrophobic yet enchanting — you’re struck by a strange sense of authenticity, a purity of intent. In an age where social media has turned consumption into a daily performance, this kind of private obsession is almost unthinkable.

In a series of statements provided to TW, Tsuzuki delved into the context and inspiration behind the surreal archive, reflecting on how much has changed since he first created these images — and why they still hold such fascination.

A Modern Religion

The series was originally titled Kidaore Hojoki, which doesn’t easily translate to English. The term “kidaore” refers to a fashion fanatic who spends excessively on clothes, combining the kanji characters for “to wear” and “to collapse.” Hojoki, often translated as An Account of My Hut, is the title of a classic Japanese essay about finding enlightenment in a 10-foot-square hermitage.

It’s a fitting title, combining the near-religious reverence each collector feels for their designer of choice with the tiny, austere homes in which they keep their extravagant wardrobes. The subjects he found were hesitant to be featured, fearing that the world would judge them for being frivolous, and some hid their faces in the photos. “But at the same time, they couldn’t bear the thought of someone else appearing in the magazine as the collector of their favorite brand,” Tsuzuki says. And so they agreed to be photographed.

A suburban, condo-dwelling salarywoman lies peacefully amid a room completely covered in vivid Anna Sui clothing, shoes and cosmetics. An Alexander McQueen devotee entering her fourth month of unemployment describes residing in an old apartment with walls so thin that she can hear her neighbor’s every move. A shy college student with hundreds of Fötus outfits in a bargain-rent Shinjuku apartment says he struggles to fund the dry-cleaning bill of his treasures.

It was crucial for Tsuzuki that these fashion disciples were not wealthy, but “rather, closer to poor,” storing their hard-earned troves of Chanel, Versace and Thierry Mugler in Tokyo’s notoriously tight living quarters. “A large house with lots of storage makes capturing the owner’s lifestyle difficult,” Tsuzuki explains. “In a small room, their everyday life — what they wear, what they eat, what books they read, what music they listen to — is inevitably exposed.”

Pursuits of Happiness

Tsuzuki approached the subjects of Happy Victims with compassion, not just from an anthropological or artistic distance. While the subjects’ unremarkable yet luxurious lifestyles were inherently compelling to unveil and to capture, he also recognized their feverish curations as an intentional art and valid pursuit.

After all, he reasons, “the world does not mock a poor bibliophile who dents their floors with a lifetime’s worth of unreadable books, or an aspiring DJ who survives on convenience store bread and packaged snacks to buy records. The depth and intensity of the passion are the same; only the object of that passion differs.”

When Happy Victims first came out in Japan, it received mixed reactions. Tsuzuki struggled to find a gallery that would exhibit the photos, and brands refused to be associated with the project, seemingly embarrassed by their most loyal customers. Overseas, though, the series was widely embraced, with museums across Paris, London and Luxembourg City eagerly exhibiting and even purchasing the prints for their permanent collections. The portraits had become coveted collectibles themselves, in a full-circle way.

Tsuzuki says that he initially expected a cynical response from overseas audiences at gallery talks. “Walking through the venue, describing [my photos] in clumsy English to participants, I felt nervous about how the Japanese youth, buried in a shocking mass of designer labels they couldn’t afford, would be perceived by stylish art fans in, say, Paris,” he expresses. “Yet, the most common reaction I got was not a contemptuous ‘I don’t understand,’ but rather ‘I have friends like that, too!’ with a burst of laughter.”

The Gates of High Fashion

The Happy Victims reissue arrives into a world Tsuzuki could likely never have imagined. The fashion industry — and perhaps more broadly, the culture industry — has dramatically transformed in the past 17 years. When these photos were first serialized, the fashion world operated in a largely hierarchical, top-down model; established brands, runway collections and publications acted as the arbiters of trends cyclically dictated to the masses, à la Miranda Priestly’s iconic “cerulean” monologue in The Devil Wears Prada.

But now that distinction is much more ambiguous. High-fashion brands are inspired by the everyday world — take, for instance, the infamous Balenciaga Ikea bag. At the same time, fast-fashion companies mimic high-fashion trends the instant they appear on the catwalk, democratizing the glittering garments that average people could once only dream of owning — albeit at a far lower quality.

“Happy Victims was created right before fast fashion achieved global conquest,” says Tsuzuki. “I also believe it was the last era in which high fashion and street fashion were strictly segregated.”

Now, trends and aesthetics zigzag in all directions, no longer gatekept by a select few authorities with influence. Highly specific aesthetic “cores” — normcore, balletcore, gorpcore — can explode on TikTok, influencing product sales and fashion editors’ decisions; something as simple as a resurfaced film or song from a past decade can sway mass taste. And of course, streetwear, too, can spawn fashion moments in a trickle-up stream. As Tsuzuki puts it, “Over the past quarter-century, fashion design has evolved into a cultural phenomenon that diffuses endlessly without a single center.”

Collecting culture is as powerful as ever today, fueled by analog nostalgia and Gen Z’s love for thrifting. But something about it has changed. It’s hard to imagine that Happy Victims would have the same resonance if it were shot now. These days, collections are flaunted, not stashed away, and too many have morphed into nearly identical piles of clutter. In a postdigital world, cultivating individual taste — a blend of fixations, preferences and aesthetic instincts supposedly unique to your eye — can feel oddly choiceless; Tsuzuki’s unvarnished portraits take us back to a time when our obsessions were, at the very least, self-inflicted.

More Info

The reissued volume of Happy Victims is available for purchase online, at Tsutaya Books and at various bookstores around the world.

Follow Tsuzuki on Instagram for updates.

Related Posts

- Tsuguya Inoue: The Father of Japanese Cool

- Tokyo’s Arimasuton Building: A Concrete Masterpiece Made Entirely by Hand

- Sashiko Gals: The Touching Story Behind Japan’s Most Unexpected Fashion Icons

- Photographing Koenji’s Vibrant Fashion Scene by Night

Updated On November 28, 2025