In Japan, reality shows seem to swing hard in one of two directions: wholesome and mild or absolutely unhinged. Last Call, a new YouTube competition series centered on kyabajo (cabaret club hostesses), undoubtedly falls into the latter category. Marketed as Japan’s first large-scale cabaret hostess audition, the show, launched on January 4, 2026, combines celebrity judges, a conspicuously high budget and challenges that range from glossy to outright jaw-dropping.

Hosted by Roland, widely considered the most successful host in Japan, alongside celebrity entrepreneur Yuji Mizoguchi, and featuring a judging panel full of hostess heavyweights like Shingeki no Noa, Himeka and Runa, Last Call turns the neon-lit world of kyabakura into a high-stakes survival show — streaming every Sunday at 9 p.m., with episodes garnering millions of views.

The Premise of Last Call

At its core, Last Call is a competition show about finding the next breakout star of Japan’s hostess scene. Contestants — dubbed “Cinderellas” — face a series of trials designed to test what really matters in the industry: looks, charisma, sales instincts, emotional intelligence and mental toughness.

But this is no ordinary audition. The kyabakura industry is notorious for widespread exploitation and objectification, and the challenges are unapologetically blunt about the realities of the job. One segment, dubbed Kami Doctor Time (“God Doctor Time”), brings in plastic surgeons to clinically evaluate each contestant’s facial features and proportions — showing just how rigid and unforgiving standards of beauty are in the nightlife world.

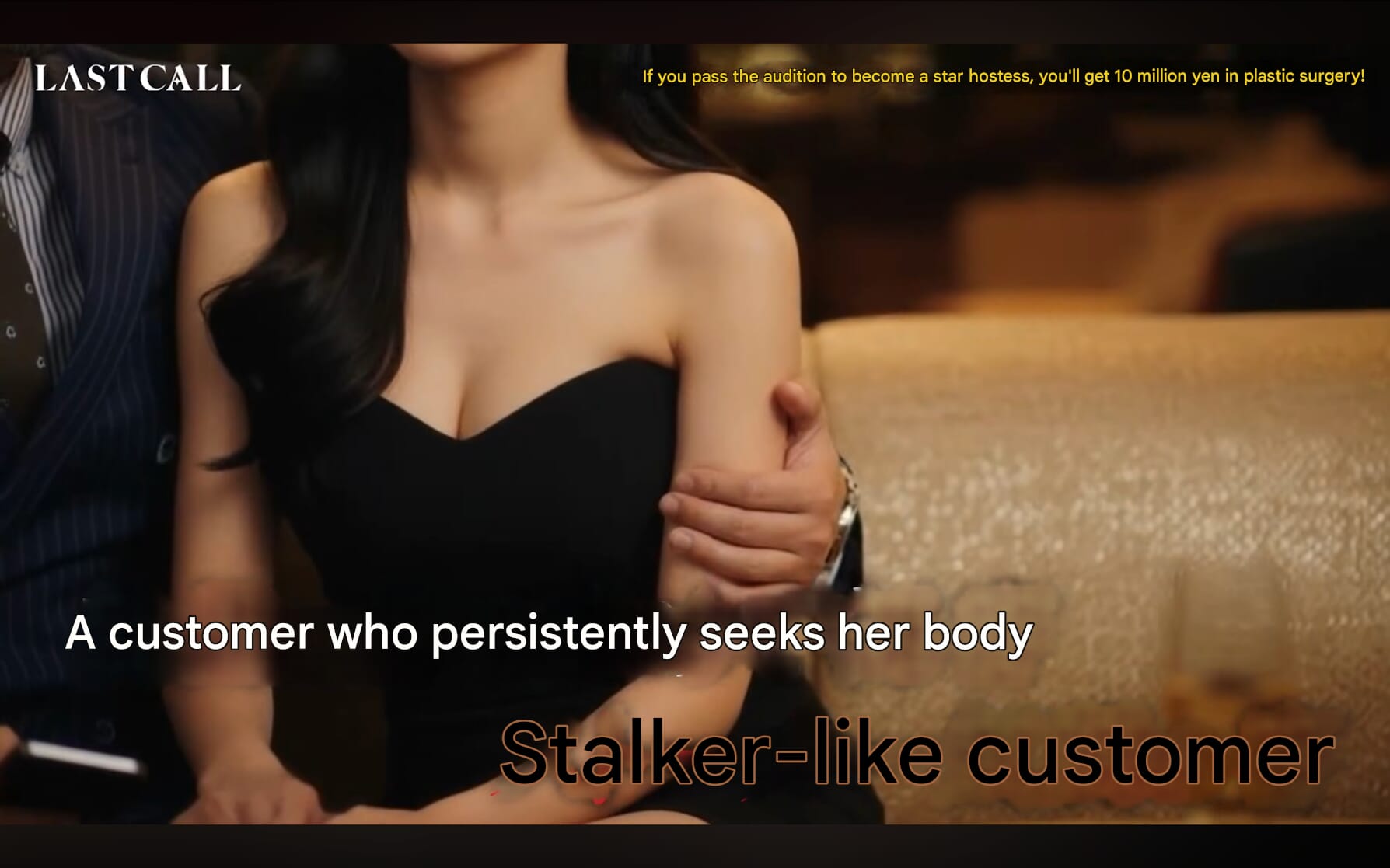

Then there’s Sekuhara Time (“Sexual Harassment Time” — yikes), a segment that’s deliberately uncomfortable. Contestants are tested on how they respond to inappropriate or creepy customer advances, a grim but realistic part of kyabakura work. The segment frames these moments as a skills test: How well can contestants maintain boundaries while keeping composure and control?

In another dystopian-feeling twist, the all-star panel of Japan’s top kyabajo delivers unfiltered feedback directly to contestants via Line, Japan’s dominant messaging and social media app. The messages are personal, merciless and read through a screen, making some of the comments feel close to bullying.

Produced by veteran TV producer Masato Ochi, the show carries a polish that sets it apart from typical YouTube reality content, while still leaning hard into the rawness of the format. By nature, it’s entertaining — deliberately shocking, with plenty of interpersonal drama and competition — but it’s also an uncomfortable and at times upsetting watch. If you watch it without thinking too hard, it’s pure absurdity, in the vein of mid-2000s American reality TV. Look a little closer, though, and it functions as a cultural case study.

On the plus side, the show positions each kyabakura hostess as someone with drive and agency, showing how they deftly navigate a system created for men. However, while it does successfully highlight the toxic aspects of the industry, it’s definitely not condemning them — something that’s best evidenced by the show’s controversial grand prize.

The Grand Prize: ¥10 Million in Plastic Surgery

The winner of Last Call receives up to ¥10 million worth of plastic surgery, fully covered by SBC Shonan Beauty Clinic. It’s a prize that’s provocative, but also deeply embedded in the kyabajo economy, where cosmetic procedures are often seen as career investments. By making surgery the ultimate prize, Last Call (perhaps unintentionally) surfaces some uncomfortable truths about beauty, labor and agency in Japan’s nightlife industry.

The show frames the prize as optional and strategic — the winner decides how (or if) to use it. Still, the message is clear: In this world, one’s physical appearance is currency.

Related Posts

- A Guide to Host Clubs in Tokyo: The Reality of Kabukicho’s Red Light District

- How Tokyo’s Host Clubs Drive Clients Into Sex Work

- I Visited a Host Club in Tokyo: Here’s What To Know Before You Go

Updated On January 30, 2026