Konami’s latest title in its Silent Hill horror series, Silent Hill F, sold over a million copies in a single day. Renowned for its psychological nightmares and grotesque monsters, the franchise has been tormenting players since its first installment in 1999.

During a Silent Hill Transmission presentation, lead producer Motoi Okamoto stated that, originally, the games were “born out of blending the essence of Japanese horror with the essence of Western horror.” But now, with the 18th iteration of the series, the studio has shifted its focus, with its signature eerie fog enveloping Japan for the very first time. As Okamoto continued, Silent Hill F is “100% Japanese horror.”

Source image © Konami Digital Entertainment

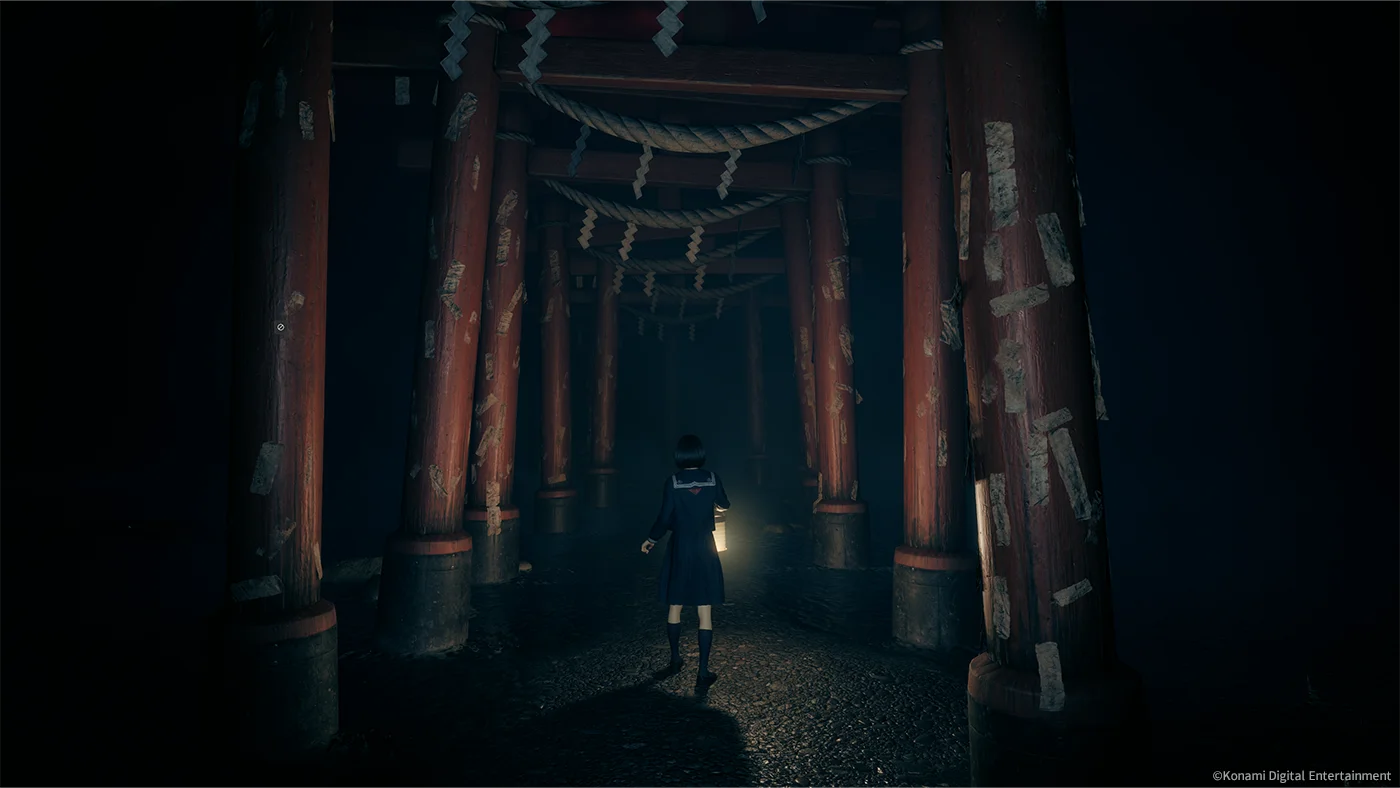

Set in 1960s rural Japan, in the heyday of the Showa era, the game has Japanese culture, particularly Shintoism, at the core of its identity and embedded into the thematic messaging of matrimony and autonomy. From the towering torii gate that draws players into the opening credits less than two minutes into the game, to “faith” being one of Hinako’s health metrics, religious motifs and traditions are masterfully woven through the storyline as players navigate the flower- and flesh-infested village of Ebisugaoka and the Dark Shrine plane.

Recognizing and understanding these many references adds an extra layer of appreciation to the game, but before we dive into specifics, a quick note: Prospective players and parents should keep in mind that the game has a CERO Z (18+) rating in Japan and an M (17+) rating from the US-based Entertainment Software Rating Board. Mature content includes depictions of sexism, child abuse, bullying, drug-induced hallucinations, torture and strong violence.

That said, here’s a selection of the abundant references to Japanese culture and Shintoism that are packed into the game. Be wary of spoilers ahead.

Gameplay screengrab (right) © Konami Digital Entertainment

Oinari-sama and Foxes

Shinto is a religion with no single founder or fixed dogmas. It does, however, have countless kami, or deities, a concept expressed in the phrase “yaoyorozu no kami” (literally “8 million gods”). Translating to the “way of kami,” Shinto focuses on the worship of divine spirits, illustrious ancestors, inanimate relics and natural phenomena.

Inari Okami, or Oinari-sama, one of the fundamental Shinto deities, represents prosperity, business, agriculture, rice and fertility. The Inari faith is widespread, with over 30,000 shrines devoted to the deity across Japan. The most prestigious is certainly Fushimi Inari Taisha in Kyoto. Boasting an extensive history of more than 1,300 years, it’s been featured in multiple films and pop culture iconography.

Kitsune, or foxes, are seen in mythology as both shapeshifting tricksters and benevolent beings, identified as messengers or familiars of Oinari-sama. Fox statues exist in multitudes at Inari shrines, where they’re often dressed in red bibs or holding the keys to the rice granary, where the harvest — essentially, life itself — was stored.

Oinari-sama makes textual appearances in Silent Hill F right away, with uncovered articles detailing rumors of “Inari-sama’s curse” infecting Ebisugaoka. And of course, foxes are prominent figures in the game, from the character Fox Mask (whose human surname, Tsuneki, is a clever scrambling of “kitsune”) to the fox statues guarding the shrine and the fox-form final boss monsters, Shichibi and Kyubi.

Gameplay screengrab (right) © Konami Digital Entertainment

Hokora

Hokora are small wayside shrines dedicated to minor kami that are not enshrined at the main grounds. In Silent Hill F, hokora serve as progress checkpoints and spots to trade offerings for faith and improved stats.

In real life, food-based offerings, like rice, mochi and sake, are left out for the deities to enjoy. As it’s believed that a fox’s favorite food is fried tofu, at Inari shrines, aburaage and inarizushi are a common sight. You’ll find this reflected in Silent Hill F’s in-game offerings.

Gameplay screengrab (right) © Konami Digital Entertainment

Kegare and Temizu

After expelling her spirit, Fox Mask calls Sakuko — Hinako’s childhood friend and a daughter of the family that runs Ebisugaoka’s shrine — a kegare, and tells Hinako that Sakuko was an “impurity that haunts you no more.” “Kegare” is the Shinto term for pollution and evil corruption, including both physical, mental and spiritual uncleanliness. It’s believed that impurities that cling to a person can bring great calamity to society, as they sever connections with the kami. The concept, mentioned in the Kojiki chronicle of ancient myths written in the year 712, is thought to have developed during the Yayoi period (900 BCE–300 CE).

Purity is one of the central principles of the Shinto faith and can be achieved by partaking in purification practices such as temizu. With temizu, one purifies oneself before entering the shrine’s main sanctuary, using a dipper to pour water onto the left hand, followed by the right hand. Then, water is used to rinse the mouth before being carefully spit out. Finally, the dipper is tilted vertically so that any remaining water trickles down the handle to purify it for the next user. This ritual is recreated step-by-step in the game by Fox Mask, as Hinako hallucinates that the water is bubbling lava.

Character image (right) from SHf Costume Design booklet © Konami Digital Entertainment

Miko Shozoku and Chihaya

Miko, or shrine maidens, are primarily young, unmarried women who serve as intermediaries between the mortal sphere and the divine realm. Miko date all the way back to the Jomon era (14,500–900 BCE), when they worked as shamans performing religious services and transmitting messages to the deities.

Though their role has evolved over the years, particularly after shamanism was prohibited in the late 19th century, they still perform duties at Shinto shrines today, aiding the head priest and overseeing the general upkeep of the shrine grounds.

Shozoku are traditional vestments, and for miko, they consist of a hakui — a white, kimono-like robe symbolic of purity — and hibakama, a red, pleated hakama (loose trousers) representing vitality. During special ceremonies and dance rites, miko don a chihaya — a white haori overcoat with flower designs or other emblems significant to the shrine — draped over top of their usual attire.

The “kegare” Sakuko and the shrine maidens who assist Hinako’s transformation rituals wear the miko vestments, complete with the chihaya. During battle, Sakuko wields a spike-covered weapon reminiscent of a miko’s kagura suzu bell staff. The usual colorful ribbons attached to the staff are replaced with a gnarly kusarigama chained sickle. The kagura suzu is used by miko to perform the kagura dance known as miko mai, a ritual to invite the sun goddess Amaterasu to spread her light. In a twisted inversion, the monstrous Sakuko’s combat choreography is directly inspired by the kagura dance, with her attacks mimicking the ringing of the bell staff.

Gameplay screengrab (right) © Konami Digital Entertainment

Shiromuku and Montsuki

The game’s Shiromuku monster gets its name from the white kimono of the same name that is worn at Shinto weddings. Shiromuku, considered first-class formal wear, are pure white so that brides may “absorb the colors” of the groom and his family.

Though simple in color, shiromuku are adorned with meticulous embroidery and woven details to create a sophisticated garment consisting of many layers. Tucked into the shiromuku is a hakoseko brocade pouch, designed to hold small cosmetic essentials such as a comb, rouge and a mirror, and a kaiken decorative dagger — a symbol of strength and the bride’s dedication to defending her new family.

In the game, the Shiromuku monster also wears a wataboshi headdress. The tall hood was originally worn by the elite to shield the skin from sunlight and mosquitoes, but it was incorporated into wedding traditions and acts somewhat like a Western bridal veil, shielding the bride’s face. Metaphorically, the headdress also serves to hide the bride’s “horns of jealousy,” a display of virtue and devotion.

Character image (right) from SHf Costume Design booklet © Konami Digital Entertainment

Matching his betrothed, Fox Mask wears a montsuki, an item of clothing adorned with kamon (family crests) and reserved for special occasions such as weddings. His montsuki has five kamon — on the chest, center back and sleeves — which evokes high formality. The kamon is also seen throughout the Dark Shrine and in the second transformation ritual, when Hinako is physically branded with the family crest to signal her position as a subservient possession. The montsuki ensemble includes a kimono, haori and striped hakama pants. Fox Mask’s haori is a bit stylized, extending into a train.

Gameplay screengrab (right) © Konami Digital Entertainment

Ema and Omamori

Shrines often offer visitors protective amulets and charms to pray for blessings and carry the faith outside of the shrine grounds.

One of the first puzzles that players face at the Dark Shrine utilizes ema, wooden votive plaques hung at shrines to ask the kami to grant wishes. The kanji characters for ema translate to “picture horse,” alluding to the original practice of using real horses as offerings.

Gameplay screengrab (right) © Konami Digital Entertainment

Visitors can also purchase omamori at shrines — small pouches that have been blessed by priests. The word “omamori” comes from mamoru, to protect. Omamori come in many varieties, with different designs, shapes and specific blessings, including health, good fortune, romance, academic or business success and wealth. The charms are popular items to hang on backpacks and handbags, a practice that brings a sense of spiritual security to everyday routines. Throughout the game, players earn various omamori that have effects such as restoring Hinako’s sanity and health points.

Related Posts

- Japanese Mythology: The Shinto Creation Myth

- 6 Japanese and Japan-inspired Indie Horror Games to Spook Out To By Samantha Low

- 3 Classic Ghost Stories That Helped Shape Modern Japanese Horror

Updated On November 4, 2025