All of my friends know I’m a book addict. When I’m not making trips across Tokyo to visit new and exciting libraries, I’m crawling the back streets of Jimbocho looking for a quick fix. It should come as no surprise, then, that my first encounters with Japanese culture were through novels. Reading Yukio Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask as a university student was my gateway to learning about Japan’s underground queer cultures.

Japanese literature has a long history of exploring sexualities and gender identities outside of mainstream norms. Even works from the Heian period, like The Tale of Genji and The Changelings (Torikaebaya Monogatari), two of the world’s oldest pieces of literature, feature queer-coded relationships such as nanshoku (same-sex pederasty) and protagonists with fluid gender identities.

After World War II, many writers became interested in portraying same-sex relationships and gender nonconformity, challenging the growing social conservatism influenced by Western imperialism. These queer authors in particular gained notoriety for their bold voices and daringness to express themselves, blazing a trail for those who came after them.

1. Saikaku Ihara

Although Saikaku Ihara may not be a “queer” writer in the contemporary sense, his works provide an important understanding of sexuality and social norms in premodern Japan. In 1687, Ihara published The Great Mirror of Male Love, a collection of stories about nanshoku featuring monks, samurai and their adolescent lovers. He was a great proponent of the beauty and purity of these dynamics in Tokugawa society, where gender did not dictate sexual preference. Notably, he aimed his stories at the “women-haters” (onna-girai), men who were only interested in other men, rather than at the “connoisseurs of boys” (shojin-zuki) who pursued both men and women, suggesting the early emergence of an exclusively homosexual subculture.

Photo credit: Kamakura Museum of Literature archives, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

2. Nobuko Yoshiya

One of the few openly queer pre-war writers, Nobuko Yoshiya was a central figure of the Japanese lesbian fiction movement. She refused the role of “good wife, wise mother,” and instead embraced androgynous fashion and traditionally masculine pursuits such as golf and horse-racing. As an author, she pioneered the “Class S” genre, which focused on intense, often romantic friendships between young women. Her most popular series was Hana Monogatari (Flower Tales), a set of 52 stories from which Yellow Rose is the only one available in English. Although Class S was banned in 1936 by the Japanese government, it experienced a revival in the 1990s and has since inspired many popular shojo manga with its transgressive and feminist themes.

Photo credit: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

3. Mari Mori

Mari Mori made her debut at age 54 with a collection of essays about her late father, literary heavyweight Ogai Mori. In 1961, she published the novel Koibitotachi no Mori (A Lovers’ Forest), the first of many that explored passionate, tragic relationships between worldly men and their younger male lovers. Her work helped found the genre that we now call “Boys’ Love” (or BL for short), comprised of homoerotic stories about men created by and for women. Mori herself is best remembered for her dramatic plots and decadent, fairy-tale settings. Although some queer activists have criticized her for glossing over the realities of homophobia, her novels captured the imagination of women seeking refuge from heteronormative adulthood and remain popular to this day.

Photo credit: Asahi Shinbun, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

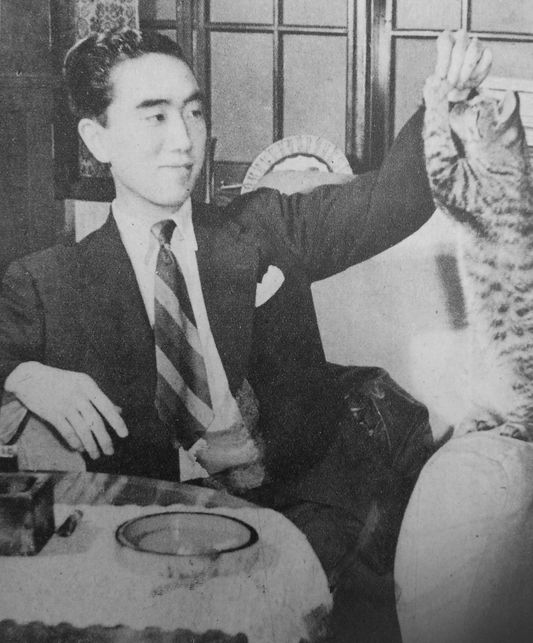

4. Yukio Mishima

Yukio Mishima was one of Japan’s most influential post-war writers, lauded for his meticulous prose and sensuality. Even so, he cuts quite a divisive figure. He’s known as much for his literary talents as he is for his hardline nationalist extremism, having died from suicide after a failed coup d’état. Although his wife and children have denied rumors of his same-sex affairs, speculation over his sexual orientation continues to this day. Many of his novels explore same-sex desire, such as Forbidden Colors and The Decay of the Angel. However, the one that has truly cemented his reputation as a queer writer is Confessions of a Mask: a thinly-veiled autobiography about a closeted young boy obsessed with death, violence and masculinity.

Photo credit: Original uploaded by Honnomushi (Transferred by ecelan), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

5. Mutsuo Takahashi

Mutsuo Takahashi is one of the most prolific and widely-translated gay writers from Japan. Although primarily known as a poet, he has also authored many novels, critical essays and plays, and continues to publish new work. He made his debut with Rose Tree, Fake Lovers, a collection of poems partially translated into English for the journal Intersections. Takahashi blurs the boundaries between high-brow literature and erotic fiction, bringing mainstream attention to the realities of underground queer cultures in Japan. He has garnered praise for his vivid, unabashed portrayals of gay eroticism both domestically and internationally and has been praised by high profile poets such as Allen Ginsberg.

6. Kaho Nakayama

Kaho Nakayama is Japan’s foremost contemporary lesbian novelist. As a young girl, she deeply admired the all-female Takarazuka Revue, which inspired her to work as a theater director and scriptwriter until her early thirties. When her acting troupe dissolved, Nakayama began writing during breaks at her office job and published her first novel in 1993. Much of her work explores the suffering and pain accompanying same-sex relationships, but her nuanced and sensitive portrayals of queer characters has won her mainstream praise and success. Her short story Sparkling Rain was published in English in 2008, as part of an anthology of queer female writers from Japan.

7. Chiya Fujino

Chiya Fujino is a critically-acclaimed author and transgender novelist who explores the lives of misfits and societal outcasts in her work. Before starting her writing career, she worked as an editor for a manga magazine until she was fired for wearing skirts to work after beginning her transition. She won the 122nd Akutagawa Prize for her novella Natsu no Yakusoku (Summer’s Promise), which is centered around a diverse group of queer characters, including a transgender hairdresser named Tamayo. English translations of her short stories have been featured in the collections Tokyo Fragments and Inside and Other Short Fiction.