Japanese female authors have only recently been gaining recognition worldwide. It’s long overdue. The rising number of translated titles have flung names such as Mieko Kawakami and Sayaka Murata into the spotlight. Aside from receiving high international acclaim, their books touch on important feminist issues. In a society where women are still pressured to meet patriarchal standards, Japanese female writers today speak openly about the female body, notions of womanhood and misogyny.

Yet these topics are not new to the Japanese literary scene. The country has had a long history of women challenging social norms through their work. Living during the turbulent late Meiji, Taisho and Showa eras, these writers, many of whom were also activists, witnessed their country undergo profound political and social transformation. In the face of changing times, the fierce language of some and the quiet but powerful writing of others spoke volumes. The work of these women not only paved the way for modern-day counterparts but continues to inspire generations of readers.

1. Raicho Hiratsuka (1886–1971)

Raicho Hiratsuka was a writer, political activist, pacifist and pioneer in the women’s liberation movement in Japan. Born Haru Okumura, she adopted the pen names “Raicho” and “Thunderbird,” reflecting her vigorous advocacy for women’s rights.

In 1911, she founded Japan’s first literary magazine written for and by women, Seito (Bluestocking in English). Her infamous opening words in the first issue read, “In the beginning, woman was the sun.” This was a reference to the Shinto goddess Amaterasu and was a call for women to reclaim the spiritual independence they had lost. The magazine received contributions from many female writers and poets and spoke on a variety of issues including poverty, arranged marriages, the legalization of abortion, female sexuality and women’s suffrage.

In her famous 1913 essay “To the Women of the World,” Hiratsuka expressed her rejection of the conventional role assigned to women as ryosai kenbo, or “good wives and wise mothers.” Publicly opposing such a traditional ideal contributed to the censorship of the magazine and other feminist publications that were a “disruption to the public order.”

Seito had a short run, being forced to shut down by the government in 1916, after much criticism from the press. At its peak, the magazine averaged 3,000 copies per month and became central to feminism efforts in Japan.

2. Akiko Yosano (1878–1942)

Akiko Yosano was a prolific poet, pioneering feminist and leading social reformer. Active from the late Meiji Period, she is best known for her controversial work Midaregami (Tangled Hair). This was her debut collection of tanka, or classical Japanese 31-syllable poems. In her poems, women are portrayed as passionate beings having agency over their love lives. They also include references to hair, lips and breasts as symbols of a woman’s sexuality and femininity.

As one would expect, the volume caused a ruckus in the nation’s literary circles when it came out in 1901. Its frank depictions of love, desire and sexuality were unprecedented for the time, particularly in poetry. Poet Nobutsuna Sasaki stated that Yosano wrote about “obscenities fit for a whore.” Unscathed by the criticism her work, Yosano went on to publish 20 volumes of poems and eleven books of prose throughout her life.

In addition to poetry, she frequently wrote for periodicals, including Seito. She advocated for shared parenting, financial independence for women and social responsibility. As a fierce proponent of women’s education, Yosano also helped to establish the Bunka Gakuin (Institute of Culture) in 1921. She was the institution’s first dean and chief lecturer.

3. Nobuko Yoshiya (1896–1973)

Nobuko Yoshiya was one of modern Japan’s most commercially successful and prolific writers active during the Taisho (1912–1926) and Showa (1926–1989) eras. A pioneer in Japanese lesbian literature, she specialized in serialized romance novels and fiction for women.

Influenced by the non-conformist ideas in the Seito magazine meetings she attended, the writer began to adopt a more androgynous style of clothing and cut her hair short. In 1916, she started the popular series Hana Monogatari (Flower Tales). Comprised of 52 stories, the collection features platonic relationships between girls and introduces motifs and symbols that became defining elements of shōjo (manga aimed at teenage females). Kibara (Yellow Rose) is the only short story out of the series that has been translated into English.

Unrequited love and hidden desire are recurring themes in Yoshiya’s work. Most of her stories have unfortunate endings — tragic death, suicide or arranged marriage — with the exception of one. Considered to be semi-autobiographical, Yaneura no nishojo (Two Virgins in the Attic) tells the story of two female dormmates who end up moving in together as a couple. The story’s ending parallels that of Yoshiya, who had a lifelong open relationship with school teacher Chiyo Monma. In her practical proposal to Monma, Yoshiya promised: “We will build a small house for the two of us.”

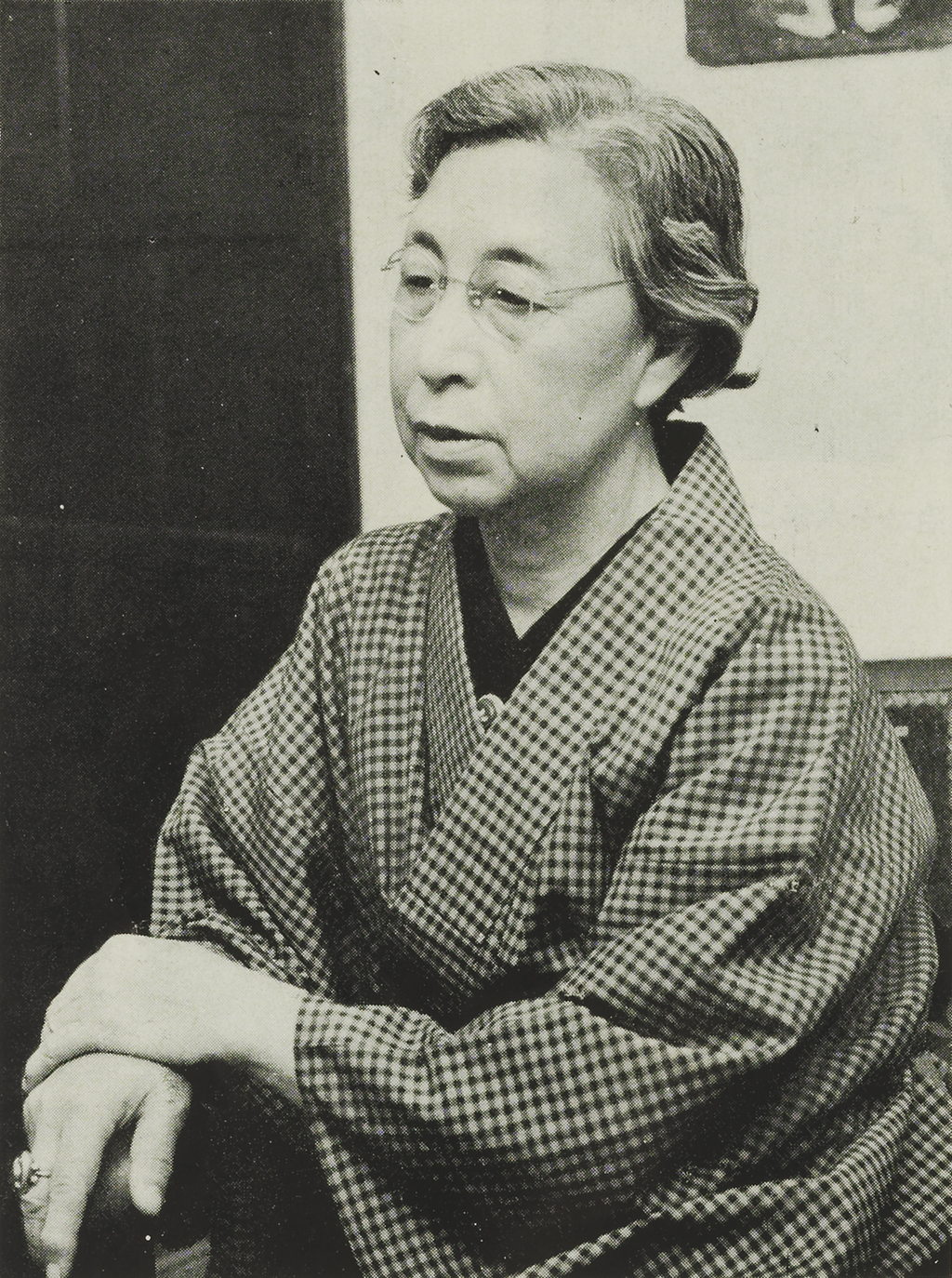

4. Yuriko Miyamoto (1899-1951)

Yuriko Miyamoto was a prominent proletarian novelist, short-story writer, literary critic and activist of the Taisho and early Showa periods. She was involved with both the proletarian and women’s liberation movements in Japan, founding several socialist and feminist publications throughout her career. Because of her activism and political views, she was imprisoned and her works censored many times.

Miyamoto’s romantic relationships inspired many of her famous novels. Nobuko, a semi-autobiographical serialized novel, was written after her divorce from her first husband. Considered a feminist work, it criticizes conventional ideas of gender and love based on male-centric narratives. After returning to Japan, Miyamoto was in a brief same-gender relationship with Russian-language scholar, Yoshiko Yuasa. This inspired another story, Ippon no hana (One Flower). Miyamoto later remarried, this time to communist literary critic Kenji Miyamoto. It was during this time that the novelist’s devotion to communist beliefs became even more fervent.

The author is also known for combining her personal experience with historical events in her works. For instance, Banshu heiya (The Banshu Plain) and Fuchiso (The Weathervane Plant), written after the war, are fictionalized accounts of her experiences in the months following Japan’s surrender. As a writer concerned with the plight of the working class, gender relations and women’s issues, her writing depicts the complexities of Japanese society through her own eyes.

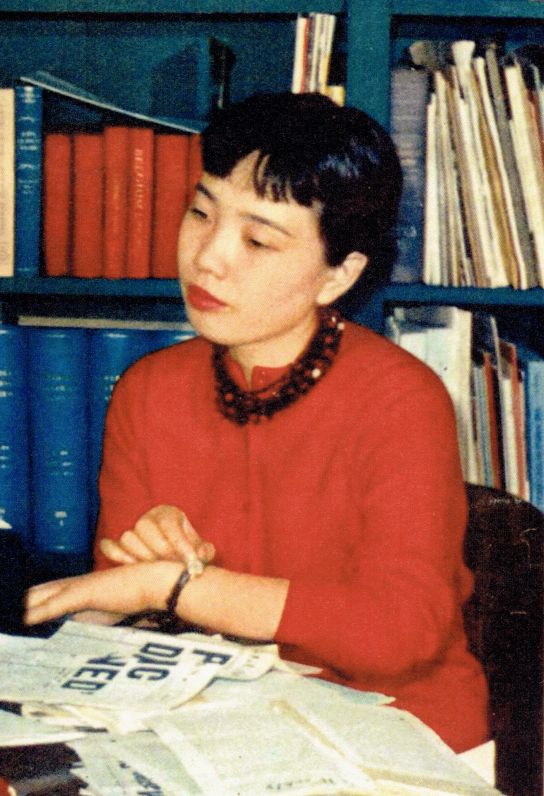

5. Sawako Ariyoshi (1931-1984)

Sawako Ariyoshi was a prolific novelist and short-story writer who authored the bestselling books The Doctor’s Wife and The River Ki. Her novels were as controversial as they were successful. Known for her advocacy of social issues, Ariyoshi examined topics that stirred up traditional Japanese norms and values. She discussed themes in her fiction ranging from the status of the elderly and women in Japanese society to environmental and racial issues.

Her first massively successful novel The River Ki (1959) follows the story of three generations of women, from the 19th century until the 1950s. An insightful portrayal of the evolving values of Japanese society, the novel depicts the inner lives of women torn between embracing tradition or modernization as their nation undergoes radical changes.

The writer reexamined the status of women in Japanese society in her historical novel, The Doctor’s Wife (1966). It chronicles the life of the women behind the pioneer doctor, Hanaoka Seishu, said to be the first surgeon in the world to use general anesthesia in surgery. In a time when women were expected to devote themselves to men, a bitter struggle arises between the doctor’s wife, Kae and his mother, Otsugi, ending in devastating results. Through her compelling writing, Ariyoshi questions the claustrophobic social customs imposed on women.