Kenta Shinohara opens a plastic case and reveals neatly arranged cutouts of mouths and eyeballs. Some mouths are tight-lipped. Some are in the shape of a toothy grin like the Cheshire cat.

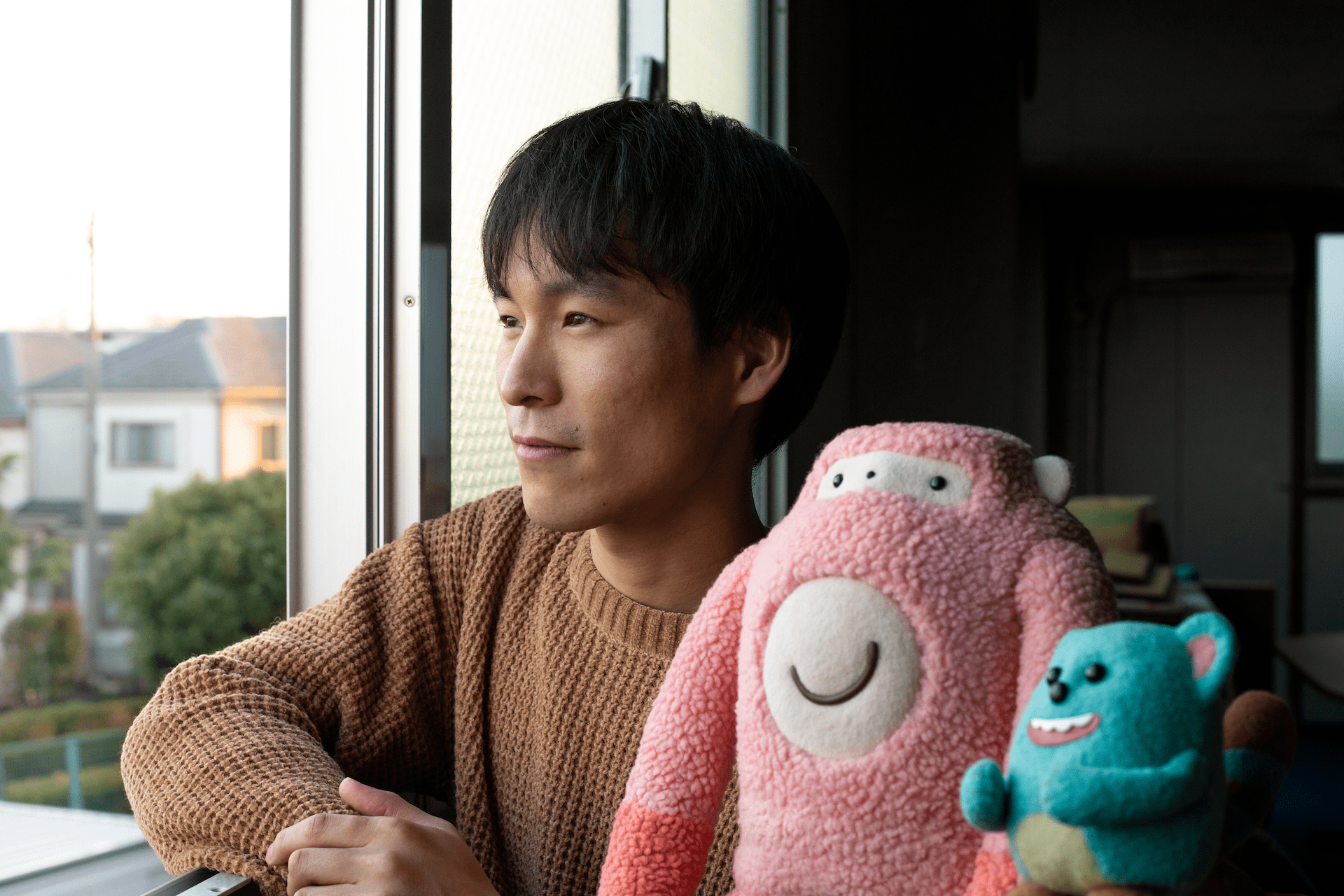

An animator with TYO Inc. and a member of dwarf studios, Shinohara pins a pair of lips to a grapefruit-sized blue figurine of the character Perol, one of the stars of the award-winning stop motion animation Mogu & Perol, written and directed by Tsuneo Goda (creator of the NHK character Domo).

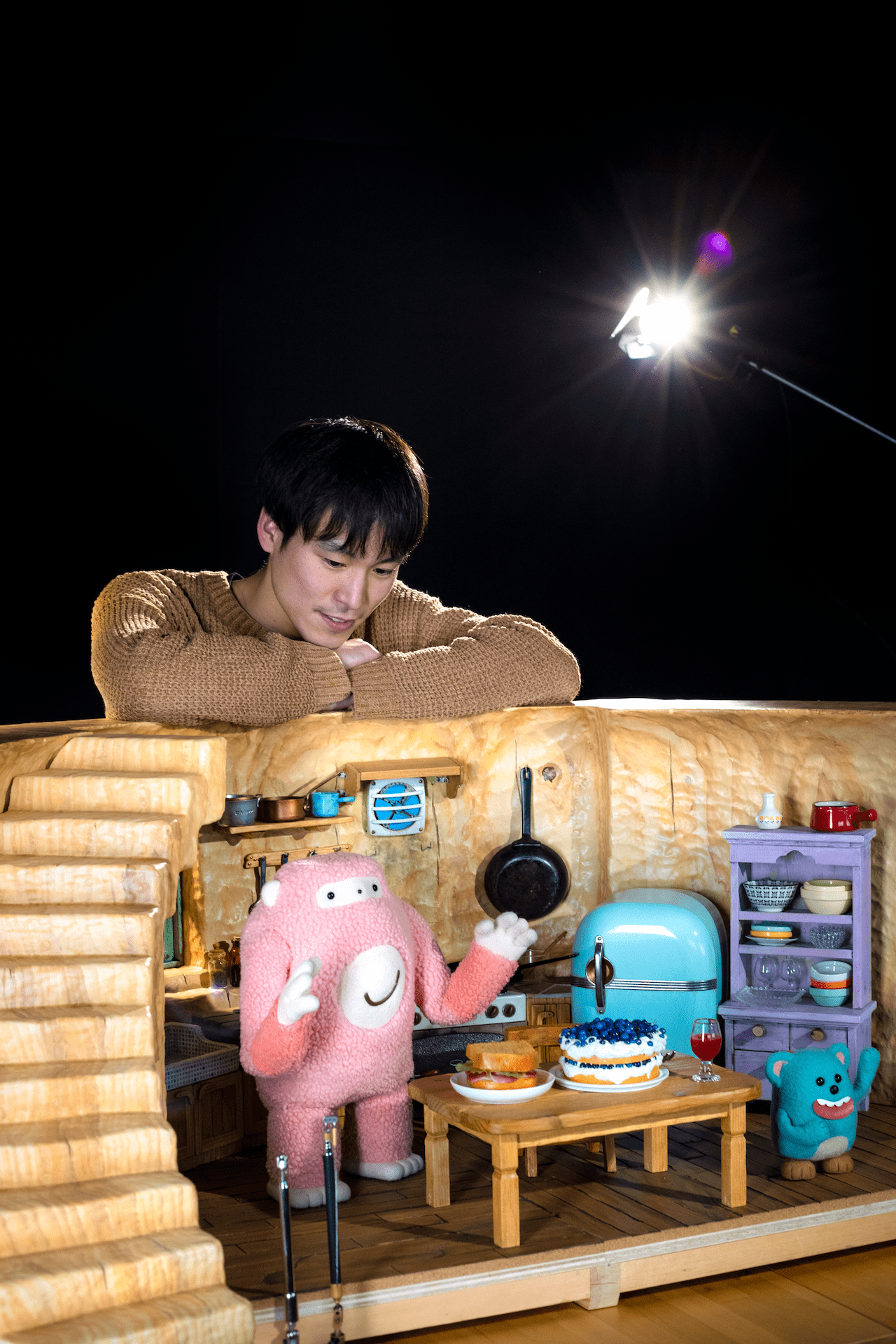

Shinohara says that since there are no mouth holes for the Mogu and Perol figurines, between each shot of filming he had to cut off bits of food – and change the facial expressions – to make it appear as if the characters are indeed eating.

Kenta Shinohara with the Mogu and Perol figurines ©dwarf

“I was in charge of the shots where the characters are cooking,” says Shinohara. “After giving it some consideration, I realized that what makes food look good is moisture, so periodically during filming I would moisten the food models. There is a shot where Mogu fries an egg in a frying pan, and we used real oil to make it look as authentic as possible.”

For his efforts on Mogu & Perol, as well as his stop motion animation work on the Netflix original series Rilakkuma and Kaoru, Shinohara was announced as winner of the Creative Choice Award at the NY ADC Young Guns awards held last November in New York City. Jurors said Shinohara’s art shows “true mastery and understanding of his field.”

Shinohara’s trip to New York City was the first time he had ever left Japan. The 30-year-old grew up playing in the mountains and forests surrounding his hometown of Shikokuchuo in Ehime Prefecture. Like most kids he was a fan of Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli films, particularly Castle in the Sky.

“With stop motion animation, you are using physical objects to create a 3D effect. Compared to CGI, which is nothing really, just data, nothing tangible, you are able to create more realistic imagery”

He discovered flip books and was intrigued that drawings can create movement. He made “probably 100” action-packed flip books depicted in the first person. His flip book of a skydiver showed the ground getting closer and closer.

Shinohara was introduced to the production of stop motion while studying animation at Osaka College of Art. He was particularly inspired by the work of Russian animator Yuri Norstein, creator of Hedgehog in the Fog. One of Shinohara’s student projects, a stop motion animation short he produced using paper cutouts, won first prize for children’s fables at an international animation festival.

“With stop motion animation, you are using physical objects to create a 3D effect. Compared to CGI, which is nothing really, just data, nothing tangible, you are able to create more realistic imagery,” says Shinohara. “The animator can inject their own energy into the figures and the scenery and make a very powerful piece.”

©dwarf

Stop motion animation has been in use since as early as 1895, gaining public attention with the 1933 production of King Kong, when pioneering animator Willis O’Brien thrilled audiences by swatting planes out of the sky with an 18-inch model of the menacing ape.

Despite the introduction of CGI, stop motion animation, often described as a painstaking process, refuses to die. Tim Burton’s 1993 stop motion animation film The Nightmare Before Christmas was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects. Nick Park’s 2005 film Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit won the Oscar for Best Animated Feature.

In an interview with The Guardian, Burton said, “There is something unique and special about stop motion: it’s more real.”

Shinohara says stop motion animation isn’t as tedious as it perhaps may seem, at least when compared to standard animation, which requires teams of animators drawing pictures repetitiously, and CGI, which requires hours in front of a computer.

“You can do quality stop motion animation with just the figures you have lying around in your bedroom”

He also likes that stop motion animation is something he can make on his own. Shorts that he creates at home in his apartment of toy action figures battling mano a mano have drawn millions of viewers to his Twitter account (@shinohara_kenta), and attracted sponsors such as Red Bull.

He started at dwarf studios, TYO’s animation studio, in 2014 as a part-time assistant, officially joining as an animator in 2016. He served as an apprentice to animator Hirokazu Minegishi.

“He taught me how to make stop motion animation from zero,” says Shinohara. “Mogu & Perol was the first time we worked on a project together, rather than me just watching the back of his head. By working together, I was able to absorb his technique and skill, which led the way for me to become a real stop motion animator.”

©dwarf

For about six weeks they worked together on a team of three to film Mogu & Perol, the Grand Prix winner at the 26th Kineko International Children’s Film Festival. The eight minute, 33 second short was shot at 12 frames per second, each scene taking about two hours to film.

Every piece of the miniature set is handmade, from the blue teapot the size of a marble to the sandwich the size of a cookie. Shinohara nimbly bends the arm of the pink, yeti-like creature Mogu a nudge forward to demonstrate how much they moved each character between takes.

Behind him are large cut-outs of the characters Domo and Rilakkuma. Shinohara says one day he hopes to produce a feature-length stop motion animation film based on characters of his own creation. In the meantime, he will continue posting short examples of his work on Twitter to inspire young people to take up stop motion animation.

“Up until now stop motion animation was made using custom-made models and it appears as if it is a difficult thing to do,” says Shinohara. “By showing that you can do quality stop motion animation with just the figures you have lying around in your bedroom, I hope that helps more people get interested in the artform. It is more fun as well.”

Photographs by David Jaskiewicz / Mogu & Perol characters ©dwarf