The round sword guard of a samurai sword worked as a counter balance to the weight of the weapon, served as protecion to the samurai’s knuckles and was the component where Japanese swordsmiths could leave their most decorative flourishes. When the Haitorei Edict banning possession of private swords was enacted in 1876, the sword guard – or tsuba – was the only part of the sword the samurai was allowed to keep.

Prior to the edict and the Meiji Restoration, during Japan’s 250 years of peace, the samurai sword had evolved into a decorative accessory for feudal lords, like a handkerchief to the formal outfits of today. Some sword guards were forged from gold. Some were adorned with the family crest. Many samurai families passed the sword guards down through the generations as heirlooms.

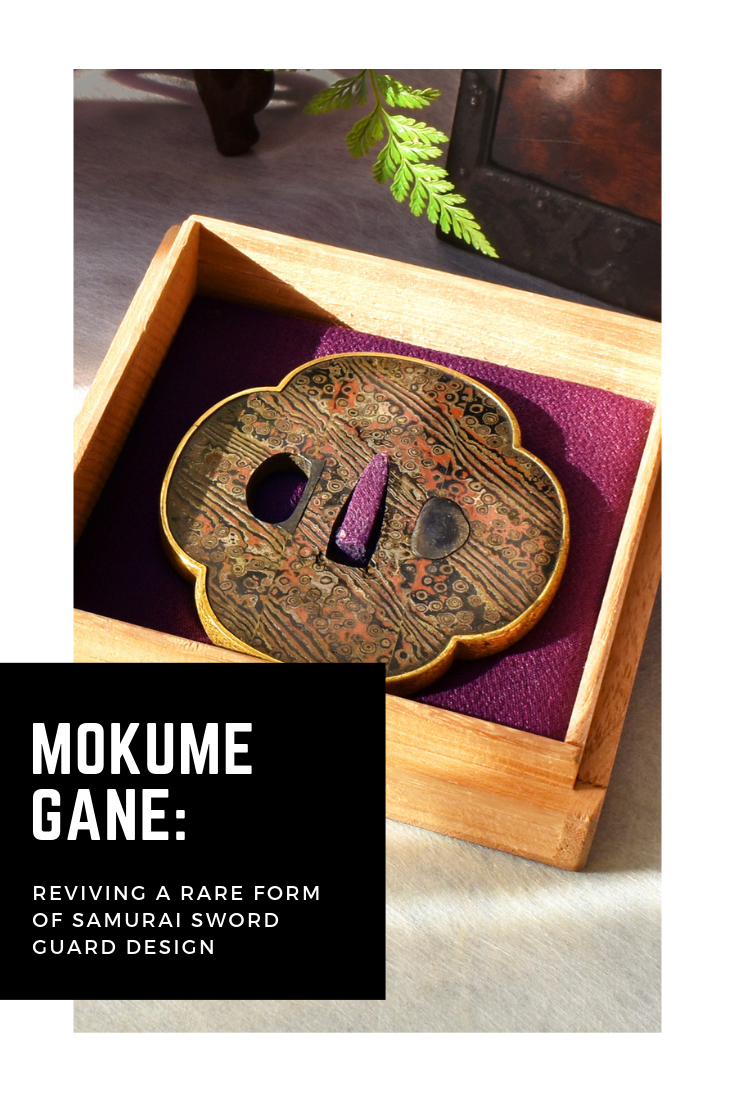

Dynasties of craftsmen dedicated themselves solely to producing sword guards. One metal-forging technique – mokume gane – set itself apart due to its intricate and unwieldly methodology and fluid and unpredictable characteristics. The originations of the artform, translated as “wood grain metal,” trace back 400 years to Akita Prefecture when the artist Denbei Shoami began experimenting with urushi lacquerware techniques, layering sheets of metal, firing them up to a nice red glow and then carving out arabesques or spiral patterns.

“You have so many different possibilities that run wild and go beyond your imagination”

The technique was perfected in Tokyo by sword guard artist Okitsugu Takahashi. Takahashi, whose skill level was a notch above his peers, layered soft metals like copper, silver and shakudo, and then painstakingly carved out otherworldly wood grain patterns.

Following the Haitorei Edict, the mokume gane technique became all but lost in Japan – a phantom artform. Meanwhile, sword guards became sought-after artifacts at museums overseas, such as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Tiffany and Co.’s mokume gane designs won grand prize at the 1878 Paris exposition.

Metalworking artist Masaki Takahashi (no relation to Okitsugu Takahashi) discovered mokume gane techniques while a student at Tokyo University of the Arts, eventually earning a doctoral degree specializing in mokume gane art. He established a research laboratory where every year he reproduces a mokume gane masterpiece to learn more about the craft and help hone his skills.

In 2003, Takahashi incorporated Mokumeganeya, a jewelry company specializing in wedding rings made using mokume gane techniques. The rings have won good design awards at home and abroad. Takahashi, who was awarded by the Society for the Preservation of Japanese Art Swords, stopped by the TW office to discuss his hopes to share this once lost artform with the world.

How is mokume gane different from other sword guard techniques?

For the other techniques, they are designing something with specific patterns for their sword guards. The artists might have poured the molten metals into a mold and then created something with a certain shape. With mokume gane, they are not bound to their plan or intentions from the beginning of the process. There is not a template or pre-determined design. They are able to create something that goes beyond their imagination and create something that is truly unique and special.

In your doctoral thesis, you say the Takahashi Okitsugu’s Yoshino River piece, which you reproduced, took mokume gane into new frontiers. How so?

The Yoshino River tsuba, depicting cherry blossoms floating on a river, and the Tatsuta River tsuba, depicting autumn leaves, made by Takahashi Okitsugu are said to be the most outstanding works among sword fittings made of mokume gane in their fusion of technique and sensibility. These are truly outstanding pieces from an art perspective, considering that they manage to capture Japan’s seasons on a surface as small as a tsuba. Takahashi Okitsugu elevated mokume gane from a simple craft of patterns to a skilled technique for displaying images. By covering the entire surface of the tsuba, he provided a prototype to match his expansive vision for mokume gane. Therefore, these two works can be seen as the culmination of the art of mokume gane as we know it today, and it is no exaggeration to say that mokume gane techniques reached their pinnacle with Takahashi Okitsugu.

What fascinated you about this artform?

When I am making mokume gane art, it is like having a dialogue with the materials. Every time you create something, it is not fixed within a certain form. You have so many different possibilities that run wild and go beyond your imagination. The sky is the limit to what you can create, and you never know how far you can go. That is what really drives me to continue creating pieces using the mokume gane style.

How did you study and master this “phantom” artform?

There are very basic techniques that all mokume gane artists know, but through reproducing the mokume gane sword guards, I am able to learn and study the different patterns, and I am also able to develop my own style.

How long does it take you to reproduce a piece?

Reproducing only takes one or two weeks. But what really takes time is studying and observing the mokume gane patterns on the sword guard. I have to determine how the artist from the past created the piece. That is the most time-consuming part, but I also enjoy the process. When you study a specific piece, you can get a feeling for how this piece was created and what method was used to produce this particular sword guard. It’s like I am creating this piece together with the original artist. And not only can I determine the method the artist used to make a successful masterpiece, but I can also see the blemishes.

Why is it important to you to keep the mokume gane craft alive?

For most people who are preserving ancient skills, they are simply trying to maintain the technique. They are not necessarily trying to improve upon it or use the technique to make something that can be used in daily life. For us, we want to take this masterful technique from the past, and bring it to the forefront of today’s industry. That’s why we continue to polish this artform and make these modern art pieces that like their mokume gane forebears, are the best in quality and beauty.

Why did you launch Mokumeganeya and start making mokume gane rings?

If you are simply preserving something, these kind of skills or techniques or technology will all disappear because they are not being put to use. You are not bringing something of new value. We want to add value to these traditional skills, so people will cherish this artform and mokume gane will not be lost again.

What projects are you working on next?

In addition to rings, I would like to also create other items that can be used in the modern household. There are a lot of possibilities. But first of all I want make the mokume gane technique more well-known. If people understand the value, there will of course be more demand or need for other mokume gane products. We want to create a bridge between these ancient skills and modern clients’ needs. There are a lot of other artists creating mokume gane crafts. I want to expand this network and make mokume gane more well-known, so people are not just interested in this field, and not only for the skill simply to continue, but to expand and blossom.

More info at www.mokumeganeya.com/e/