Brian Christian reflects on how language defines who we are, and why we should encourage linguistic curiosity in our children.

When I was about 10 years old, one of my Primary School teachers chalked a saying on the blackboard (it was, after all, a very long time ago) that I have never forgotten: “Once you learn to read you will always be free.” It stuck with me because I happened to be at that wonderful stage as a young reader when I was just beginning to understand how it was possible to lose yourself entirely in the pages of a good book. Half a century later, even in the busiest periods of the school term, I still make time for a few minutes late at night or early in the morning to free myself from thoughts of work by escaping into someone else’s story.

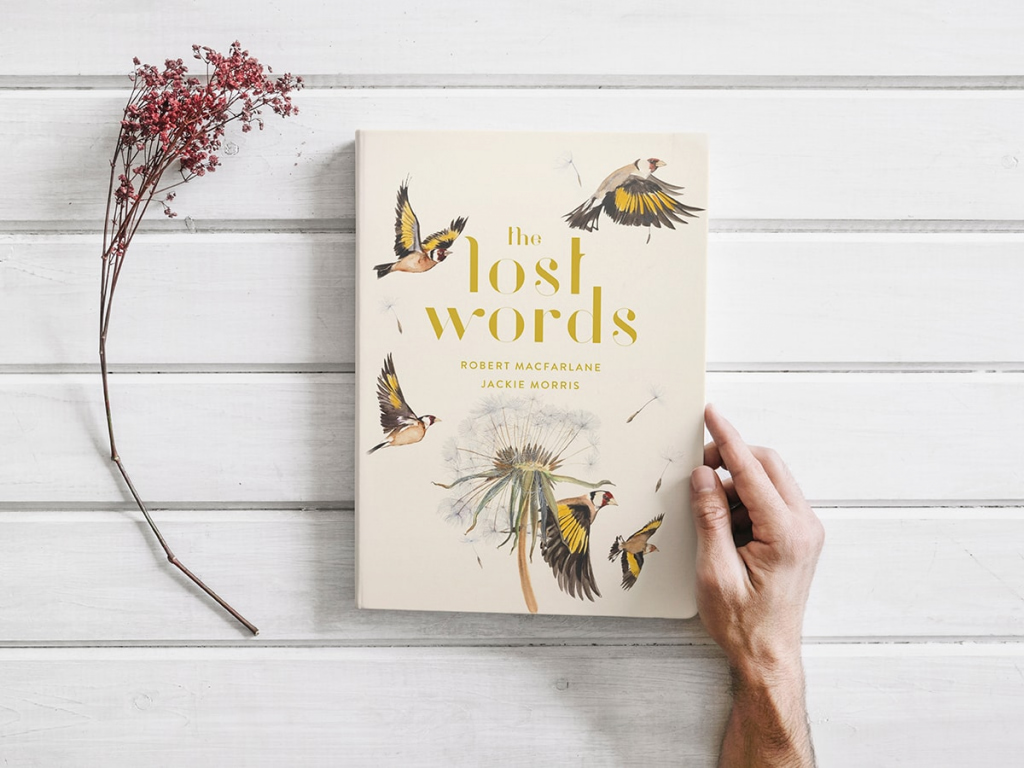

It is no wonder then that books have become the go-to option for friends and family looking to tick me off on their festive shopping lists, and over the years I have become accustomed to unwrapping packages of a fairly uniform shape and size on Christmas morning. This year, though, there was something of a surprise under the tree: the rectangular shape was familiar enough but if this was a book, it was going to be hard to find a space on my bookshelves big enough to accommodate it. Nevertheless, a book it proved to be – and bigger than most in more ways than one.

The Lost Words, written by Robert Macfarlane, with exquisitely beautiful illustrations by Jackie Morris, offers a passionate creative response to a series of contentious decisions made over a number of years by the editors of the Oxford Junior Dictionary to cull words once seen as central to the lives of young children and replace them with substitutes apparently more relevant to today’s world. Out went “acorn”, “bluebell” and “conker”, for example, and in came “attachment”, “blog” and “chatroom”.

Macfarlane’s introduction to The Lost Words is telling and heartfelt: “Once upon a time, words began to vanish from the language of children. They disappeared so quietly that at first almost no one noticed – fading away like water on stone.” In what he calls a book of spells rather than poems, he then sets out to make good the loss: “blackberry” and “kingfisher”, “otter” and “raven” are tenderly re-gifted to future generations of children.

It is a remarkable book and one that offers the clearest of insights into the complex relationship interwoven between our environment, our imagination and our vocabulary. And while its roots are firmly planted in the fertile soil of a very British landscape, it piqued my curiosity about similar riches of expression in the Japanese language. Let me share just three of the gems I unearthed.

A very loose translation of boketto might be “to gaze into the distance with an empty mind”. Not day-dreaming, because to dream is to conjure up a picture – this is a focus on a blank canvas or perhaps no focus at all. A transient moment of drifting vacancy.

Ichigo Ichie may literally be translated as “one chance, one meeting”. It’s an expression derived from Zen Buddhism closely associated with the arcane rituals of the tea ceremony but it might be more familiar to some as the Japanese subtitle to Forrest Gump. In essence it exhorts us to recognise the unique and fleeting nature of every encounter, every experience.

And then there’s wabi-sabi: the appreciation of beauty in imperfection and in the natural cycle of growth, decay, and death. It celebrates and embraces the wear and tear and the frayed edges that time, the unforgiving elements and loving use leave behind. Imagine the red rust of the fallen autumn leaf or the fading colours of a favourite family photograph, the silvery grey of weathered wooden boards or the spongy moss on an old wall.

I am firmly of the opinion that our language helps to define who we are and that it colours the way in which we perceive the world around us. This is why The Lost Words is so important and why we should encourage linguistic curiosity in our children. There is a reason why expressions such as boketto, ichigi ichie and wabi-sabi have no direct counterpart in English; they are representative of a specific cultural outlook and derived from particular aspects of a national psyche. While I recognise that languages are organic, living and growing and changing all the time, we must understand that if we allow words to be lost we risk losing a part of what we are – or who we might become.

Brian Christian is the Principal of the British School in Tokyo.