If you want to terrify yourself, read Matthew Walker’s Why We Sleep. Granted, this is not really the book’s objective, but if you’ve ever disregarded sleep or considered it an unnecessary barrier to productivity, it will make for uncomfortable reading.

Before becoming arguably the world’s foremost public expert on sleep, Walker was an unassuming English scholar conducting research in the labs at the University of California, Berkeley. Then, in 2017, when he published one of the most influential pieces of popular science writing in recent memory — a New York Times best-seller that has been translated into more than 30 languages (including Japanese) — his public profile exploded. He has since appeared on popular podcasts, like The Joe Rogan Experience and The Diary of a CEO with Steven Bartlett, as well as conducting a TED Talk titled “Sleep is your superpower” and teaching a Masterclass on the “Science of Better Sleep.”

In Why We Sleep, Walker writes with passion and eloquence, detailing in layman’s terms the latest data in sleep research and “the good, the bad, and the deathly of sleep and sleep loss.” Here’s how he sets the tone:

“Two-thirds of adults throughout all developed nations fail to obtain the recommended eight hours of nightly sleep.

“I doubt you are surprised by this fact, but you may be surprised by the consequences. Routinely sleeping less than six or seven hours a night demolishes your immune system, more than doubling your risk of cancer. Insufficient sleep is a key lifestyle factor determining whether or not you will develop Alzheimer’s disease. Inadequate sleep — even moderate reductions for just one week — disrupts blood sugar levels so profoundly that you would be classified as pre-diabetic. Short sleeping increases the likelihood of your coronary arteries becoming blocked and brittle, setting you on a path toward cardiovascular disease, stroke, and congestive heart failure. Fitting Charlotte Brontë’s prophetic wisdom that ‘a ruffled mind makes a restless pillow’, sleep disruption further contributes to all major psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety, and suicidality.”

This is just a short excerpt from the first of 300-plus pages that expound upon this message in similarly matter-of-fact prose. And you’ve likely guessed what this has to do with Japan.

The World’s Most Sleep-deprived Nation

There are various studies on the world’s most sleep-deprived nations — from the World Sleep Society, the Sleep Medicine journal, or apps like Sleep Cycle and Fitbit — and when Japan is included, it sits dazed and delirious at the top of the list. With an average nightly sleep time of just over six hours per night, Japanese adults fall nearly two hours short of the recommended amount. And remember, that’s just the average, meaning a significant proportion of the population is sleeping considerably less.

Walker argues that every major organ within the body and process within the brain is optimally enhanced by sleep, and therefore detrimentally impaired when we don’t get enough. Let’s take testicles as an example.

Men who regularly sleep five hours a night have significantly smaller testicles than those who sleep seven hours or more. Sleep-deprived men also have a level of testosterone that matches that of someone 10 years their senior. This leads to erectile dysfunction, depleted libido and other reproductive issues.

As Japan faces a population crisis — the number of annual births has dipped below 800,000 for the first time since statistics were first compiled in 1899 — Fumio Kishida is entreating his electorate to go home and reproduce. Perhaps the prime minister ought to be telling them to “go home and sleep, and you’ll reproduce of your own volition.”

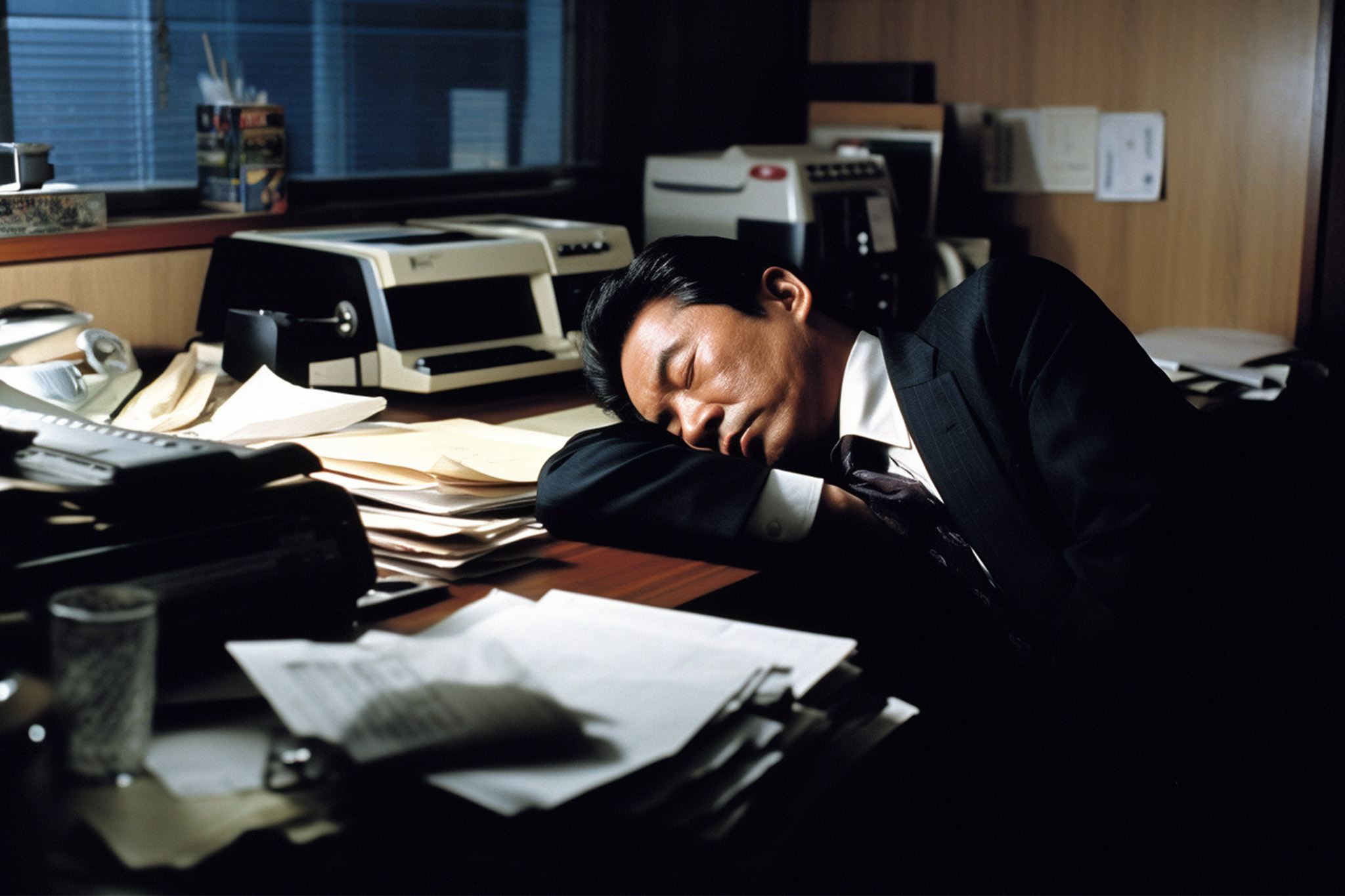

Corporations vs. Sleep

A sleepless society is also a financially hindered one. The Rand Corporation found that Japan loses on average 600,000 working days per year due to lack of sleep, hemorrhaging up to $138 billion in the process.

But the typical Japanese workplace ignores this fact. The term karoshi, premature death from overwork, exists for a reason. This stems from a company-first lifestyle that was encapsulated by a recent cause célèbre. Let’s call it The Tale of the Severed Finger:

In Maizuru, a provincial city on the Sea of Japan coast, a young boy is walking home from school. Just another care-free, spring afternoon in a town where not many incidents occur, just as the locals prefer it.

The boy’s wanton gaze then locks onto something unfamiliar: blood is splattered and pooled by the roadside. His curiosity gets the better of him and he goes to inspect the scene. A severed fingertip, nail still attached, lies abandoned amid the gore.

He rushes home to tell his mother of his discovery. Distressed, she calls the police.

The authorities determine the source of the fingertip fairly quickly. An aging courier had parted ways with it when it got caught in the sliding door of his delivery van. He then faced an ultimatum: plow on with his rounds to avoid bringing the company name into disrepute or seek immediate medical attention.

Some things, as the Japanese maxim intones, cannot be helped. But at least the driver’s rounds were completed.

The point is not that the delivery driver’s accident was a result of sleep deprivation, although, given how it affects brain functionality, that also is a possibility. But rather to highlight the default condition of corporate Japan: one where employees are subservient to the company at the expense of their physical and mental well-being. Whether that’s working through a serious injury, or prioritizing time spent in the office (or in the van) over time spent asleep.

When society is waging a war on sleep, it becomes harder to embrace it. To give in to what is essentially a coma, often interrupted by surreal and worrying visions of seemingly symbolic importance. Sleep will consume approximately a third of your life, resigning you to inactivity, while your to-do lists grow longer.

But, of course, that is missing the point. The emerging sleep narrative is that of a potent tonic, a wellness elixir, that, when applied effectively and for the correct duration, improves the quality of your waking hours on earth.

“To sleep,” writes Walker in simpler terms, “perchance to heal.”