by Rick Kennedy

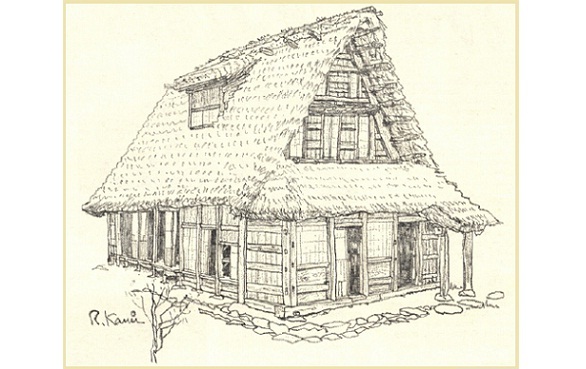

A glimpse of what it must have been like to live serenely in the Japanese country side 200 years ago.

Some people dream of living in a sleek penthouse ringed by a wide terrace from which every evening they could look out on a twinkling city. Others imagine that they could find contentment in a small Queen Anne country house of perfect proportions. Still others would like nothing better than to live out their days in a simple Polynesian hideaway set back from a silken beach.

Me, if I had my choice, I would make my home in an old Japanese farmhouse.

This is not a personal quirk. Many people, Japanese as well as foreigners, have been struck by the quiet harmonies of traditional Japanese rural architecture. Some have gone so far as to buy one of the magnificent old farmhouses called minka and have it disassembled and reconstructed on their plot of land in Kamakura or Kauai or Rio. City people’s fantasies about living this way are in fact now so commonplace that if you should approach a real estate agent in rural Japan and tell him that you are looking for a house, he will begin drawing up a list of abandoned minka for you to inspect.

Minka of classic design in reasonably good condition are difficult to come across, however. They have been recognized as the treasures they are: the most beautiful dwellings ever produced by a rustic agrarian society. Assuming you could find one. it might well cost as much as you would pay for a modern house, and if you wanted to move your minka (which is entirely feasible as these old farmhouses were constructed without nails), you would need to hire a crew of expert Japanese carpenters as well as a heavy crane, because a minka’s structural beams are massive, weighing a ton. These house were built as Stonehenge was built, to last forever.

Although you might not be in a position just at the moment to think seriously about buying your own minka, you can prepare yourself for that eventuality by inspecting at your leisure a collection of 20 superb examples of minka gathered from all over Japan—most of them solemnly designated “Important Cultural Properties” by the Japanese government — in a tranquil, garden-like setting just a half hour from Shinjuku. It makes for a pleasant half-day outing and offers the best possible insight into the genius of Japan’s traditional architecture.

At Shinjuku Station, buy a ¥140 [now ¥250] ticket for Mukogaoka-yuen on the Odakyu Line. Leave Mukogaoka-yuen by the South Exit. You’ll see a map posted showing how to get to Nihon Minka-en, It’s a 15-20 minute walk straight through town out into the surrounding hills. Just follow the monorail tracks until they bear off to the left. You keep going straight. It’s ¥300 [now ¥500] to enter.

At the top of a short slope you encounter the first minka, a 150-year-old inn with built-in stable. Walk right in. It is cool and dark inside, as open as open as a forum. The inn of Suzuki could put up perhaps 20 guests and their horses. Here, as in all houses in Minka-en, a plaque explains in Japanese and English the provenance of the structure, and you can inspect a faded photograph showing it in its original setting.

Next is the house of Ioka, the dwelling of a merchant who sold lamp oil and incense in Nara 260 years ago.

As you leave Ioka’s house, you will hear the muffled thumping of the 120-year-old mill and the water wheel groan.

Then the house of Sasaki, who was chief of his village in Nagano. This is perhaps the most beautiful minka of them all, with an utterly unadorned facade 25 meters across and delicate beams and pillars. The pillars. The house is open to nature, and off to one side is a sophisticated little garden.

The route from house to house is well marked. You wind along the path through the woods, and when you emerge into a clearing there will be a minka like Emukai’s 250-year-old gassho zukuri-style house from Toyama Prefecture, with its great cathedral-like roof pitched very steeply in order to prevent snow from accumulating, or the elegant house of Yamada with its brass door fittings, tatami-edged with brocade, and a thatched roof two feet thick which serves to keep the house warm in winter and cool in summer.

Yamashita’s house is majestic, with a roof soaring as high as a modern four or five story building. Why not stop here for lunch? A bowl of sansai soba (noodles with various mountain ferns) is ¥500 and a glass of sweet amaake is ¥250. In the cold weather you sit on cushions around a wood fire set into the middle of the floor, just as did the Yamashitas.

The minka are arranged as if in a mountain village. A fine balance is struck between the need to protect and preserve the houses and the desirability of maintaining the illusion they remain in the original setting.

Here is a storehouse from Okinawa, built like a little temple, and here the house of Hirose, with thick walls and small windows and straw mats strewn around like area rugs, and a tiny altar tucked away in the eaves. (Minka, as the houses of the peasantry, were not allowed to have tokonoma in which to hang a scroll, and decoration for decoration’s sake is in minka virtually non-existent.)

The house, which are pervaded by the lingering aroma of wood smoke, are held together by prodigies of tying—split bamboo and hempen ropes. A small room in a minka is 16 mats, twice the size of a large room in a posh modern Tokyo apartment. But minka had to be large: some of them sheltered extended families of 50.

Up a steep path to an antique Kabuki theater brought here from a fishing village in Mie Prefecture, then down to a valley containing a cluster of houses from the Tohoku area and a tiny boatman’s hut (circa 1939), evocative of Mr. Thoreau’s hut on Walen Pond. You think: yes, I could live like this.

When you leave by the rear exist of Minka-en, keep bearing left past the fountain, past the planetarium, and you will come out where you entered.

Minka-en is closed Mondays and some holidays. Call (044) 922-2181 to check.

External Link:

Nihon Minka-en, Wikipedia

Main Image: Wikimedia Commons