by Gary Cooper

“THE TREES?” RESPONDS KINZO Murata. “You want to know about the trees?” He ponders the question and peers from one of the windows of his three-bedroom penthouse apartment. Maybe all he sees is the concrete and steel that grows faster than the fastest bamboo. Maybe not.

“The last tree was over in that direction,” he says ruefully, pointing generally toward the American Embassy.

“It was a 600-year-old ginko and it was destroyed in an air raid during the war, along with most of Roppongi.”

There was a time when everyone knew of the six trees that gave Roppongi (literally “Six Trees”) its name. It was a fabled time. Like a dream. Hard, maybe impossible, to imagine.

Farmers from the sleepy village of Shibuya would make their way along the ridges of rice paddies, through emerald stalks of bamboo, across a grassy plain.

Foxes and badgers could hear them approaching and scatter to their hiding places. The farmers came to gather wood. Roppongi was a good place to find it. It was a pine forest.

The resettlement of the military government to the village of Edo along the bay meant little, in the early 1590s, to the wood collectors.

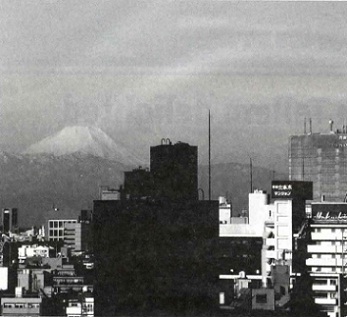

The days were clear then. And they could see from the height offered by the hills specks of fishermen working in the great body of water now known as Tokyo Bay. They could also see the mountain called Fuji, named by the ancient Ainu aborigines for their fire deity. Later, they could watch the building of the Castle of Edo.

Kinzo Murata turns his leathery face from the glare of the glass. His memory spans only 69 years. He has little information about the five other trees. He doesn’t think they were all ginko; at least one was a giant keyaki (zelkova).

And it would seem likely all the trees were approximately the same age, and that they graced the rolling hills, embracing the intersection that today has become one of the most international crossroads in the world.

There are other theories of how the name originated. Through the feudal Tokugawa Era, Daimyo, or governors, were required by the military regime in Tokyo to be present in the city as much as half of their time. Their families, moreover, often had to reside in Edo permanently, as sort of in-the-flesh political collateral.

A number of these Daimyo maintained estates for their families in the lush hills of Roppongi. Six of these families are said to have had last names ending with the word for tree, according to one version, hence the appellation “Six Trees.”

It wasn’t until 1660, however, that the name is considered to have taken hold. That was the same year the Aoyama Waterway was extended to the area, and thirsty Roppongi-ites could quench their dry throats with the crystal waters of the Tamagawa River. The place was called Ryudo-mura Roppongi.

Roppongi had made an early mark in history about 30 years before; one that, as much as anything else, signaled commercial development as well as eventual botanical doom.

The occasion was the death of Shogun Hidetada’s wife in the autumn of 1626, the same year Peter Minuit “bought” the island of Manhattan for 24 dollars worth of trinkets from a bewildered bunch of Indians in North America.

Roppongi was chosen as the site for her cremation, and the funeral procession that carried her remains reportedly marched on a carpet of pure white cotton (considerably more valuable then) that extended from Roppongi to Zozoji Temple in Shiba. It was a spectacular affair involving the cream of upper class society and samurai, decked out in full regalia like knights in shining armor.

The funeral, in other words, was a tremendous success. In appreciation for their services, the four Buddhist priests who handled the arrangements were rewarded with 1,000 tsubo each.

Until then they had lived ascetic lives in simple forest huts between Zozoji and the Imai-cho valley, where the U.S. diplomatic corps’ Grew House is now located.

Inspired by their newfound wealth, the four priests resolved to develop the hillsides. They built new temples and in front of the temples erected more than 30 shops and houses to entice new settlers. They came and Roppongi began to prosper.

Disaster seems always near at hand, then as now. In those days its most frequent form was fire. Flames destroyed Roppongi, and much of Tokyo, so regularly it would be pointless and possibly impossible to note each tragedy. The more significant fires occurred in 1668,1716,1760,1845, 1900, and more recently, the napalm-kindled destruction of World War II.

Roppongi was very much a country village in the 1790s when it officially became one of the 808 towns under the administration of the Edo municipality. The center of metropolitan activity swirled around Asakusa and Nihonbashi. Roppongi was a good place for catching fireflies and listening to cicadas.

In the mid-18th century, the population of Roppongi stood at 454. Mikawadai, current site of the Hamburger Inn, housed 51 people. There was no “Roppongi Crossing” in those days; in fact, there was no road from Tameike to Kasumiyacho. The main thoroughfare was the road that today runs behind the Azabu Police Station. It was known as Onari Kaido, and Shogun often used it on their way hawk hunting.

The pages of Roppongi’s history are not without their tales of romance. During Edo it happened that a young samurai from Fukui drew the duty of accompanying his lord on one of his one-year stints in the big city. He became enraptured with the charms of a nubile maiden who worked for his lord.

When his year of temporary duty expired, he received orders to pack up and return to Fukui. But he couldn’t do it. In flagrant regard of the supposedly unshakable Bushido spirit—but like the legendary romantic hero of so many cultures—he hung up his samurai swords and walked into the sunset with his maiden.

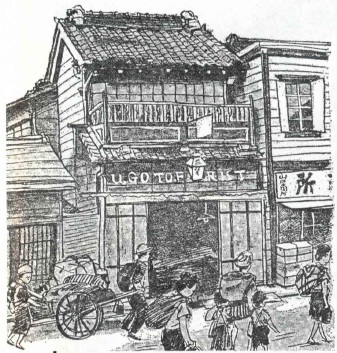

In this case, the setting sun apparently caught them in Roppongi, for it was here that they settled, opening a vegetable shop that stood until just before the Pacific War.

It may have been that Roppongi was blessed with an L. Mendel Rivers-like representative lobbying for the constituency within the central government, but at any rate, in 1890 it was determined that the Imperial Guard’s Third Division will be moved from Marunouchi to Ryudo-cho, where Pacific Stars and Stripes, the U.S. military newspaper, and part of Tokyo University are now.

The soldiers brought money. And Roppongi was good to the military, with many shops catering especially to the soldiers. A night life blossomed.

Perhaps it’s merely coincidence, but the first police box was inaugurated in Six Trees about the same time. Until then, the townspeople had policed their own neighborhood.

Streets still were unpaved and were filled only with horses and jinrikisha.

It may have gotten a little noisy down in Mikawadai, though, from the sounds of cows being milked at the sprawling dairy farm there.

During and after the Japan-China War of 1894, Roppongi grew famous as a heitai machi, or soldier town. Many troops shared rooms rented to them above local shops. The Russo-Japanese War in 1905 brought an even greater influx of military, and the little country town no doubt began to garner a reputation that stands today of catering to military men enjoying R&R.

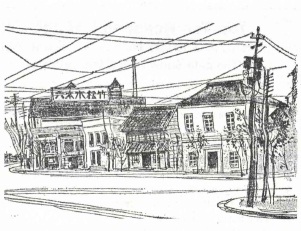

In 1911 and 1912 the jinrikisha were nosed to the roadsides by the coming of the first streetcars, stretching from Aoyama 1-chome, through Roppongi, to Mikawadai and, of course, linking with the rest of Tokyo.

It was about this time that 13-year-old Kinzo Murata made his way from his family’s Ginza tailor shop, through the fields and woods, that still sprinkled the suburbs, to begin his life’s work stitching clothing.

As he sewed in his shop a few yards from the main crossroads, he watched the continuing transformation of Roppongi.

The first official foreign embassies opened in Roppongi during the early Taisho period, some 10 years before the Great Kanto Earthquake leveled nearly everything from Mt. Fuji to Tokyo.

It was then, in September 1923, after the earth trembled and 143,000 died, that Murata began to notice a change come over Roppongi and, indeed, much of the eastern and uptown portions of Tokyo’s outskirts that had been spared devastating damage.

The homeless sought refuge in parts of the city untouched by fire, and Roppongi, for a change, had been left relatively unscorched.

Murata figures the earthquake was the turning point, so to speak, of his quiet little neighborhood. The homeless stayed. Commerce prospered.

The 600-year-old ginko tree got a few years older and life was tolerable. In 1925, the government railway’s Yamanote belt line fastened, putting Murata’s tailor shop and Roppongi permanently within the steel rail circumference of the city.

World War II was not to be as lenient with Roppongi as the Great Hanshin Earthquake had been. Napalm bombs blanketed the city, converting it within a few months before the end of the war into a Dresden-like inferno. More men, women and children were killed in the fire bombing of Tokyo than in the American atomic bombings of both Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Roppongi was gone. Rubble. Standing in ruins that were once pine forest, then city, then nothing, a person could once again see clear to the sea. But there was little life between.

Ironically, the same GIs who brought the bombs landed with the bread, and it was the Allied Occupation, with its high concentration of conquerors in Roppongi, that helped in post-war rehabilitation and internationalization of the area. The U.S. Army’s 1st Cavalry Division and Signal Corps sprinkled the area and the Sanno military billeting facility (literally officer’s hotel) is still located only a figurative stone’s throw from Roppongi.

Along with, and perhaps because of, the number of international soldiers who roamed Roppongi, this Roppongi Zoku (Roppongi Crowd) as it was nicknamed, featured the latest fashions, hip slang and a tendency for keeping late hours. As the foreign troop presence dwindled, the late-night shops, bistros and boutiques found willing clientele among the Zoku and entertainers who favored Roppongi with their off-hours.

Today, Roppongi rages like a gastronomic United Nations flaunting the culinary arts of at least 20 nations. Square foot per square foot, few districts anywhere can boast its awesome potential for killing such a myriad breadth of epicurean hunger.

Murata has turned his tailor shop into a boutique, featuring the latest styles, denims, bell-bottoms and corduroys.

“Most of the old-timers, like me,” he says, “have had to do something. We couldn’t stay the way we were. The competition was just too tough.” Many have torn down their old wooden frame structures, mortgaged their property and put up office buildings.

It’s a lucrative move. The rent for 3.3 square meters of floor space in Roppongi is $6,000. Any kind of office needs at least 66 square meters, and the deposit alone could be $120,000. (According to Alistair Machray, Senior Manager Corporate Services at IKOMA/CB Richard Ellis, today’s prices for all class buildings average $29,000 per month with a deposit of $348,000 for the same space.)

Kinzo Murata and his Roppongi have come a long way. The trees are gone, but Roppongi has turned into a gold mine. Murata, in addition to owning the boutique, is vice chairman and chief of the business department of the Roppongi Shopkeepers Association, as well as active politically as vice chairman of the Roppongi Town Council.

But where does Murata—a man who has been intimately intertwined in the growth and greening of Roppongi, a man who knows its back alleys and secrets like few others—where does a man like Murata go when he steps out to dine?

“I don’t,” he says. “I never eat out. Always eat home. I can’t afford to eat out in Roppongi. It’s just too expensive.”

Roppongi Timeline

1598 – Tokugawa leyasu moves Zozo-ji Temple to current site under Tokyo Tower.

1626 – Shogun Hidetada’s wife dies – Rop-pongi is chosen as the site for her cremation.

1660 – Roppongi name takes hold.

1668 – The first of five fires in the next 250 years that destroy the area.

1750 – Population stands at 454.

1890 – First police box is opened.

1894 – Japan-China War. Roppongi becomes a soldier town.

1905 – Russo-Japan War. More soldiers arrive and bring the nightlife with them.

1911/1912 – Linked to the rest of Tokyo by the first trolleys.

1913 – First Foreign Embassies are opened in Roppongi.

1923 – Great Kanto Earthquake. Roppongi is spared from devastation.

1925 – Yamanote Line is completed.

1945 – Reduced to rubble by American fire bombing.

Post war – Regains reputation as international entertainment district during the Allied Occupation.

1958 – Tokyo Tower is opened.

1964 – Tokyo Olympics. The opening of the Hibiya Subway Line helps make Roppongi the top nightspot.

1986 – Ark Hills complex is completed.

Mid-1980s – Mori Building starts to buy properties in the Roppongi 6-chome section in preparation for the Roppongi Hills development.

2002 – The Soccer World Cup comes to Japan. Roppongi is the focal point of international fans’ celebrations.

2003 – Roppongi Hills complex due to open for business.