With clattering and clanking forests of scaffold and infinite convoys of machinery, Japanese cities are constructed, deconstructed and reconstructed endlessly around the ears of their mostly uncomplaining residents, who shrug off this pile-driving madness with practiced Zen-like forbearance. The round-the-clock jamboree of electronic chirrups, jingles and amplified messages — both commercial and advisory in nature — that make up the remainder of the trembling air, are for the most part accepted as being in the natural order of things. And perhaps they are.

Despite, or perhaps in direct response to this noisy climate, a select group of Japanese musicians from the 1970s and 1980s, taking their cues from Aki Takahashi’s influential performances of Erik Satie’s pre-minimalist ‘furniture music’ and the then-current ambient experiments of Brian Eno, created a new and distinctly Asian music of stark and transcendent tranquility. These serene and stylish soundscapes, temporarily forgotten at home, and until recently widely unknown elsewhere, have seen a contemporary surge of interest — in no small part thanks to that unexpected friend to musical archeologists of the non-mainstream; YouTube. This latter-day enthusiasm for kankyo ongaku (“environmental music”) has been stoked by the involvement of Spencer Doran of Visible Cloaks, who as well as overseeing a genre-defining compilation for crate-digging specialists Light in the Attic, has put out much-coveted re-releases on his own Empire of Signs label, jointly run with August Croy of Root Strata records.

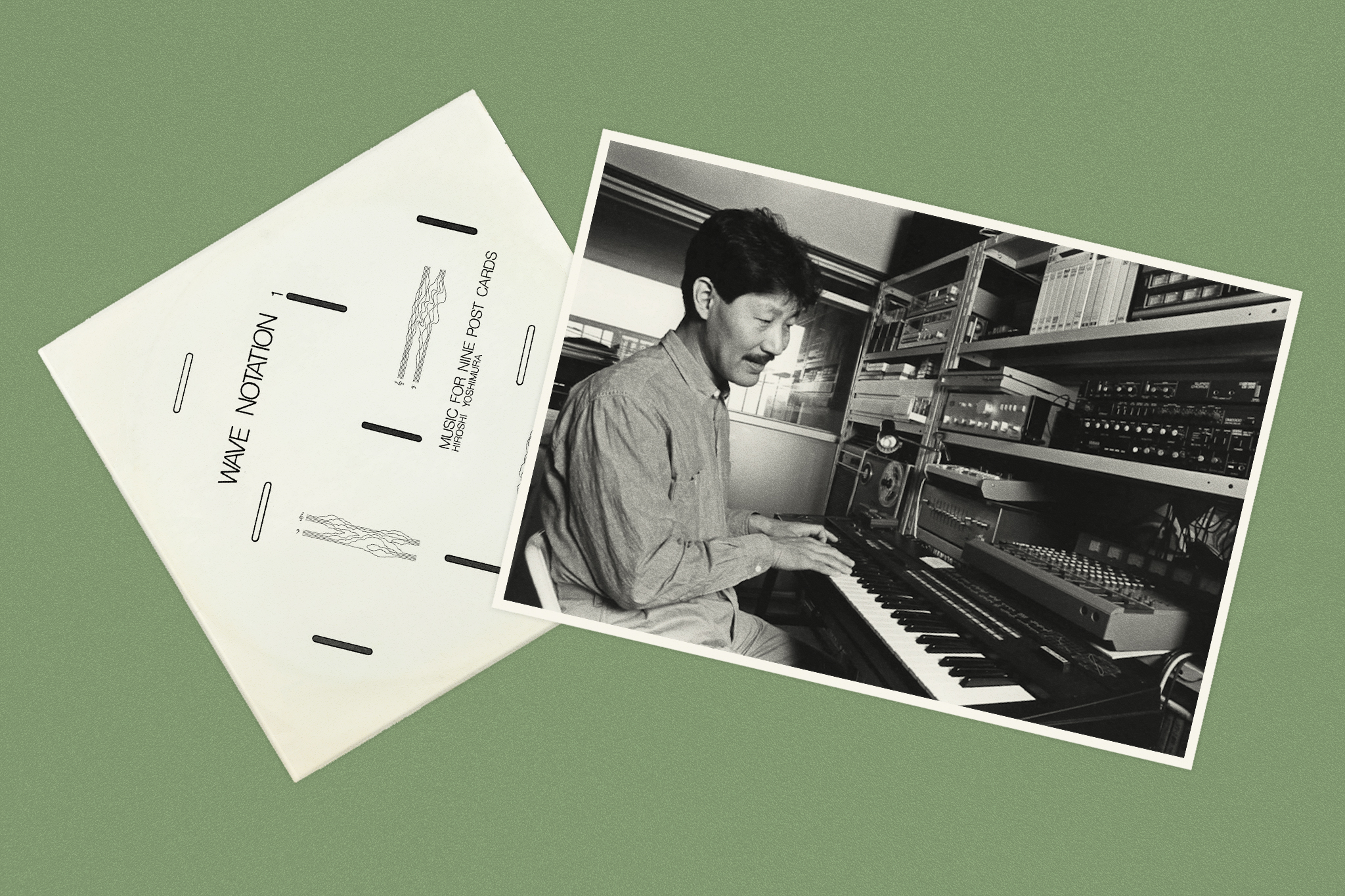

As well as contributions from YMO’s Ryuichi Sakamoto and Haruomi Hosono, those acorns and arborists of Japan’s post-60s musical family tree, this period saw important works by Yasuaki Shimizu, Satoshi Ashikawa and Inoyama Land, among others. The essential ephemerality of their often site or event-specific compositions lends them an austerely nostalgic sweetness that makes them irresistible to melancholic modern listeners. Some of the warmest glow of contemporary (re)discovery has been reserved for the blissed and boundless sonic safe-spaces of Hiroshi Yoshimura, who spent a busy lifetime making music that was anything but, before sadly dying of skin cancer in 2003. Glowingly received reissues of his official debut, Music for Nine Post Cards, and his quietly joyful classic of ambient nature worship, Green, make it likely that Yoshimura’s unassuming influence will spread wider in the 21st century than he would ever have thought possible.

Born in Yokohama in 1940, Yoshimura’s childhood was spent in wartime Japan. He was a keen musician and began his studies of piano aged 5 just as World War II was drawing to a close. Graduating from Waseda University’s Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences into the whirring cultural and economic dynamo of mid-60s Japan, he was influenced by American microtonal composer Harry Partch as well as the Yoko Ono-associated interdisciplinary art movement Fluxus. Interested in all things creative, Yoshimura busied himself with music, poetry and graphics as well as working on sound design for electronics company Toa and starting a computer music group called Anonyme. Alongside his own creative efforts, he worked on music and sound design commissions from art galleries, architects, fashion houses, television and cinema, as well as teaching at both Chiba University and the Kunitachi College of Music.

Music for Nine Postcards

Recorded at home with just a keyboard and a Fender Rhodes, Yoshimura provided the tape of Music for Nine Post Cards to the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, where it was intended to complement the clean and airy interior of Jin Watanabe’s Bauhaus-inspired building. The sublime and often sun-dappled stillness of his near-pointillist reflections on such simple but fundamental themes as “the movements of clouds, the shade of a tree in summertime, the sound of rain, the snow in a town”, received much positive attention from enchanted museum visitors, resulting in the music being given a wider release as the first of Satoshi Ashikawa’s influential three-part Wave Notation series. Yoshimura’s precise but sketch-like meditations on nature and architecture may have been intended for a place and time now gone (the Hara Museum closed its doors in 2021), but they continue to offer listeners a light filled sanctuary and a space for contemplation.

Green

Yoshimura’s fifth album was one of the artist’s own favorites and has gone on to achieve something of a cult status; original pressings of the 1986 LP reaching prices into the thousands of dollars. The restfully inviting tones that make up the immersive arcadian landscape of Green have none of the hard-edged sheen sometimes associated with the Yamaha synthesizers Yoshimura used to create them — they glimmer rather than glint, and echo with a warm and gentle clarity. Recorded over the winter of 1985, the music of Green carries a light-on-the-horizon sense of anticipation for the coming of spring. There is a joyful bubbling sound to the music that gives it an air of quiet celebration. Offering something more than just a calming respite, Yoshimura’s ambient classic provides listeners with a space for hopeful and openhearted meditation on the inevitability of life’s redeeming cycles and the timeless potency of what Dylan Thomas called, “The force that through the green fuse drives the flower.”

The Audio Ecosystem

Things have not improved in the four decades since Ashikawa, writing in the liner notes to his 1982 album Still Way, stated, “We should have a more conscious attitude toward the sounds — other than music —that we listen to.” His pleas fell on ears that if not deaf, were otherwise engaged — already surrendered to the tide of aural flotsam and became one with the urban maelstrom. Ashikawa, who died shortly after making Still Way — the second installment of his Wave Notation series and his only personal recording — would not be surprised that the sound levels of 2023 have not returned to those of a pre-industrial idyll, but would probably be disappointed by the lack of modern concern for what he called “the audio ecosystem”.

However, for sensitive souls, lost and overwhelmed by sound, there are modern solutions to a modern problem. The Walkman, Sony’s life-changing invention of 1979, as well its many descendants — ubiquitous now in the form of the smartphone — mean that changing your environment is as simple as reaching for your headphones and pressing play. Thanks to the photosynthetic sounds of people like Ashikawa and Yoshimura, for a while at least, the nerve-frazzling city can become a sunlit forest clearing and the nasty drills and sirens just the chattering of birds.