Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein premiered in October to critical acclaim and has already found its way to Netflix, giving people around the world a chance to ponder questions first posed by Mary Shelley’s classic novel. For instance, can a pursuit of knowledge be dangerous or immoral? Maybe even evil? Hopefully not, because while watching the movie, we asked ourselves a different question: If, like Victor Frankenstein, you tried to make an artificial human — but in feudal Japan — how would you go about it? These are the potentially dangerous answers that we came up with:

The sanskrit syllable “A” as used in the Shingon buddhist Ajikan meditation

The Power of Words

In a way, Victor Frankenstein’s monster, or the Creature, was something of a flesh golem: a body crafted from corpses and infused with life. Only, in the movie, it was done via electricity instead of a golem’s shem: a slip of paper spelling the sacred names of God in Hebrew, which animate the human-made shell. The need for electricity — and fresh corpses — poses a problem when endeavoring to create a samurai-era Creature, of course. But there might be a way to get around that by going back to the original golem myth.

The Man’yoshu, an eighth-century collection of poetry, mentions the concept of kotodama, or “words as repositories of supernatural power.” This may have influenced the belief in shuji seed-syllables, which were Sanskrit characters (perceived as much more mystical than kanji) that essentially were … gods. The written letters themselves were believed to embody a powerful deity, very similarly to how the golem’s shem worked.

One of the most potent shuji was the Sanskrit letter “A” used in the Japanese a-ji kan rite meant to harness the power of living, divine energy captured in written form. We can combine this with some Buddhist beliefs, like those of the Shingon school, that see all things as physical manifestations of the Buddha. In esoteric Buddhism, there’s no real difference between the animate and inanimate. This non-duality doctrine was also used to erase the difference between Buddhas and Japanese kami, theoretically allowing for the animation of a “dead” body using the godly power of one of the Yaoyorozu no Kami (literally “8 million deities” but meaning “infinite deities”) through holy symbols.

Such a ritual was never documented. However, the building blocks for constructing a Frankenstein’s monster-equivalent golem — be it from clay, stone or maybe even sewn-together flesh if you went to the Street of Bones — and infusing it with a spark of the divine are all there in the more hidden corners of Japanese spirituality. All they need is a feudal Japan-era Victor Frankenstein to put them together the right way.

Example of a 17th century Karakuri automata

God in the Machine

Frankenstein-inspired stories with a robot Creature made from metal instead of meat are kind of old hat by now. Even Japan kind of got onto that train with Pluto, the gritty reboot of Astro Boy. But could such a story be possible in a time before electricity? Technically, every story is possible in the realm of fiction, but an “alive” robot with free will in, say, 17th-century Japan? That would actually have some historical and cultural basis.

Japan has been making robots since before the invention of gunpowder. The feudal Japanese art of robotics peaked with the karakuri automata. Spanning many different varieties, these machines moved via all sorts of means, including complicated clockwork mechanisms or simple whalebone springs. Some could perform quite sophisticated tricks like shooting a tiny arrow or serving tea. But other karakuri served much loftier purposes. Their role was to act as vessels for gods.

The dashi karakuri automata were large puppets paraded around on floats during religious festivals. Following the same principle as the omikoshi portable shrine, these purified, mystical-seal-containing robots were considered to be inhabited by specific deities during times of celebration. They were quite literally divine machines.

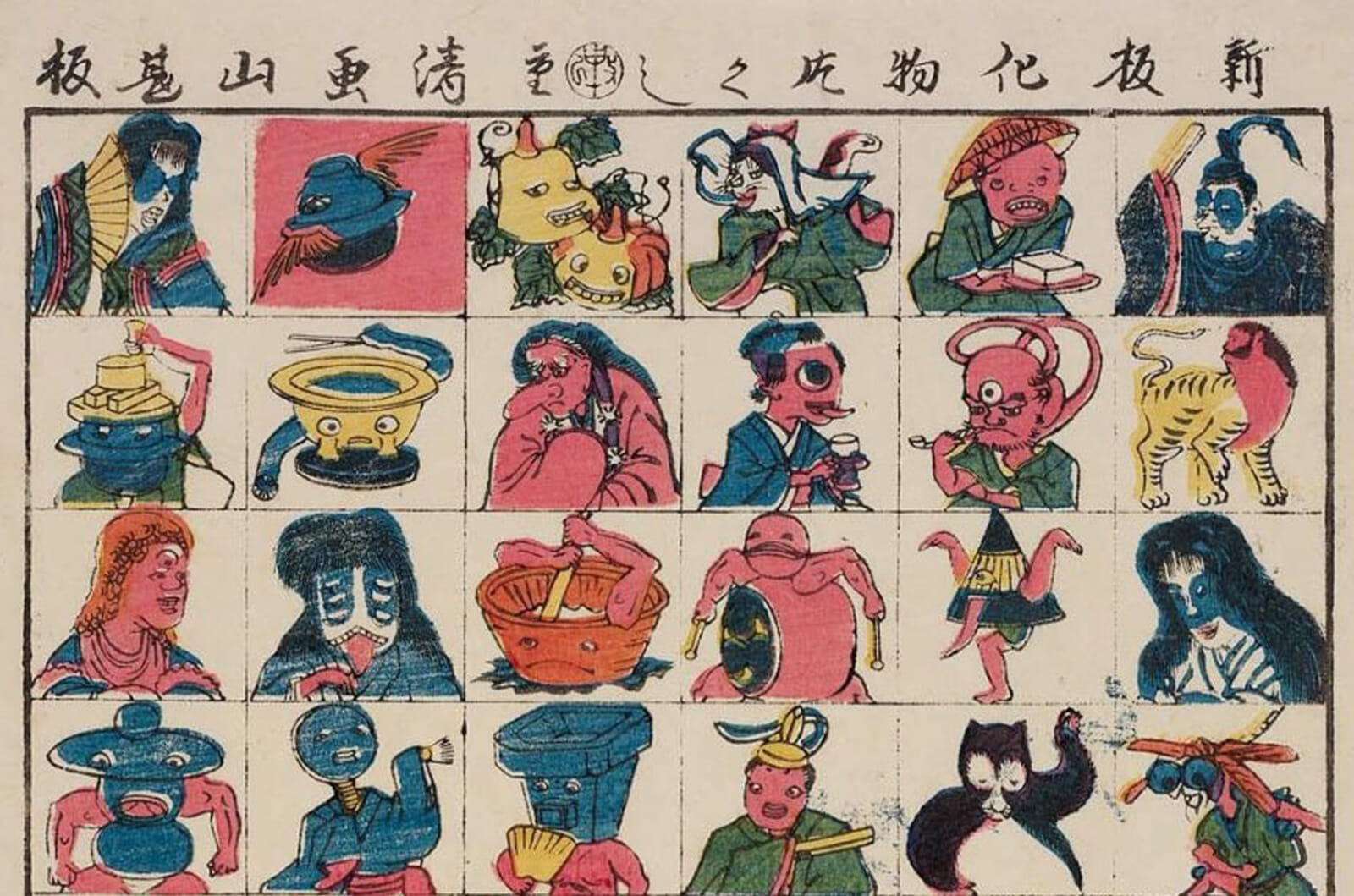

So, is the idea to treat a rogue kami-inhabited dashi karakuri as a Japanese version of Frankenstein’s monster? That’s definitely one way to go about it, but we can do better thanks to tsukumogami lore, which states that any object, even an umbrella, can achieve sentience after 100 years. It just needs to have been cherished by humans, accumulating our spirit energy that eventually brings it to life.

Japanese mythology is full of stories of collective belief being a source of great power, so if enough people truly believe that a dashi karakuri lives, and then we abandon it for a century, it could gain life and, as is sometimes the case with tsukumogami, seek revenge for being forgotten. Honestly, that’s about as Frankenstein as it can get.

Depction of an onmyōji performing divination with counting rods, from the Nara picture book “Tamamo-no-Mae,” early Edo period | Wikimedia / Kyoto University Library

The Servants of Government Tech-Wizards

The onmyoji were genuine Japanese tech-wizards employed by the government’s bureau of magic, because Japanese history is awesome. They did everything from performing exorcisms to astronomy and even engineering. Aptly, their shikigami creations also weren’t pinned down to one role.

Depending on the time period and the onmyoji himself, they could be anything from a projection of one’s will to a kind of magical curse or even a paranormal being that took physical form.

Shikigami servants weren’t confined to a human shape (in fact, they often took the form of animals), but they usually started out from an anthropomorphic position. Shikigami were conjured from magical objects like talismans, with the most common summoning item being a human-shaped doll made from paper or grass. Since in Japan’s ancient animistic beliefs, which the onmyoji incorporated into their arsenal, everything contains life energy, the inanimate shikigami talismans could either generate their own spiritual power or channel one from another source, including a human soul.

In any case, with the right combination of summoning texts, chanting and hand signs, a feudal Japanese tech-wizard could conjure up a being that could move, touch and think. There was, however, a catch to this that serves as a handy entryway to “shikigami as Japan’s equivalent of Frankenstein’s monster”: While meant to be servants of onmyoji, a shikigami could escape their control and become free (especially if the summoner was inexperienced or weak-willed, or if they lost focus), often choosing to attack the one who brought them into the material world without considering the implications of their actions.

Mary Shelley would have sued for copyright infringement if such a story came out of Japan during her lifetime. Now, though? It would make a perfect reimagining of Frankenstein set in a time of Japan’s state-appointed magic engineers. It’s frankly weird that we’re the first ones to propose this idea.

Example of tsukumogami objects, depicted in “A New Collection of Monsters” by Utagawa Shigekiyo (c. 1860)