Here’s an interesting fact: According to two independent international surveys released in May, Japan ranked sixth (out of 190) in a list of the most desirable countries to emigrate to, while landing at 54th (out of 59) in the best countries to work and live in as an expat. At face-value, the two results are wildly conflicting and present a curious dichotomy.

If you look for some quick cause-and-effect theories, you’ll likely find them. For example, anyone who’s paid even cursory attention to online hype forums and Japan travel social media pages over the last 15 months, will have seen that the desire to visit or emigrate to Japan has scarcely wavered in light of the pandemic. Moreover, a record 1.7 million foreign workers were recorded in October 2020; a 65,000 increase from the previous year.

During the same time period, however, many expatriates already living in Japan expressed concerns over the government’s ethnocentric pandemic border policies and corporate malpractices stemming from the partial shutdown of society. As I reported here last year, Japanese labor NPO Posse fielded hundreds of complaints from foreign nationals subjected to workplace discrimination in spring 2020 alone.

Yet, these feel like entirely reductive conclusions. Does Japan’s stellar global image really set expectations it can never meet? Is Japan a victim of exoticization, only for new arrivals to find something altogether unpleasant and unsettling? And is the data significant, or even relevant to individual experience?

📈Two Middle Eastern cities (#Dubai and #AbuDhabi) and two Asian cities (#Tokyo and #Singapore) now rank higher than #NewYork on the list of most desirable #work #destinations. #DecodingTalent #digital #talent #report #thenetwork #global pic.twitter.com/pdw5hvwZ4R

— The Network (@The_Network) March 17, 2021

A Work-Mobility Survey

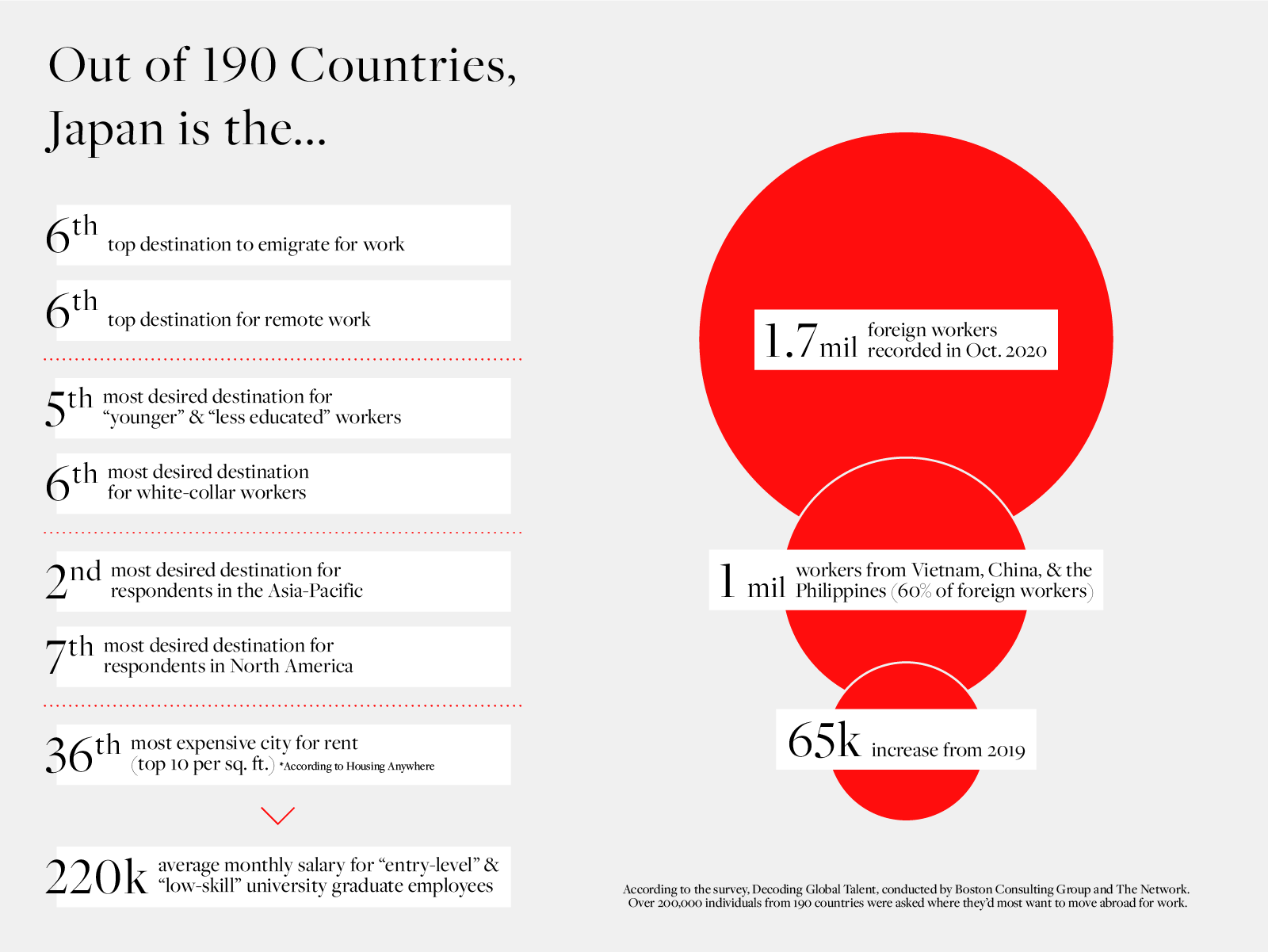

The first survey, Decoding Global Talent, conducted by Boston Consulting Group and The Network, asked over 200,000 individuals from 190 countries where they’d most want to move abroad for work. Japan has been firmly in the top 10 of the survey since 2018. Its lofty position of number six is, therefore, true to recent form.

The survey also noted an overall decline in the desire to relocate for work. This has decreased by 13 percentage points since 2014. It left space for a new emerging pattern: top destinations for remote work, in which Japan also ranks sixth. Some may find this strange given telework was still something of a pariah’s game until Covid-19 struck. Even since then, it’s hardly been ubiquitous (as many a begrudging office worker could attest).

Perhaps it’s easy to see Japan as a more viable destination for corporate bigwigs and workers in high-income brackets. According to data collated by Housing Anywhere, Tokyo is the 36th most expensive city in the world for rent. If analyzed per square foot, though, it would land somewhere around the top 10. Annual salaries for entry-level and “low-skilled” employees, meanwhile, are relatively paltry, averaging 220,000 yen per month for university graduates.

A Land of Opportunity?

Japan does, however, do well across several demographic verticals which belie the assumption it caters exclusively to the top income percentiles. Japan ranks as the sixth most desired destination for white-collar workers, yet fifth among the “younger” and “less educated”. It also scored seventh among respondents from North America and second behind only Australia for respondents in the Asia-Pacific region. People from Vietnam, China and the Philippines account for over 60% of the total number of foreigners in Japan. Collectively that adds up to well over one million, yet many work manual labor and “low-paying” jobs. This speaks to Japan as a land of potential opportunity. It also likely reflects the trend of Southeast Asians immigrating alone to send remittances back to their respective families.

As an aside, Japan does not currently offer manual labor visas. This is circumvented through the Technical Intern Training Program which offers employment and training for foreign nationals from developing economies –Vietnam, China, and the Philippines make up the top three nationalities in the program. It has come under fire in recent years, however, for sub-standard working conditions and human rights abuses. In response, the independent watchdog Organization for Technical Intern Training was established to accredit companies connected to the program, though its success has been questionable.

— InterNations (@InterNationsorg) May 9, 2021

A Quality-of-Life Survey

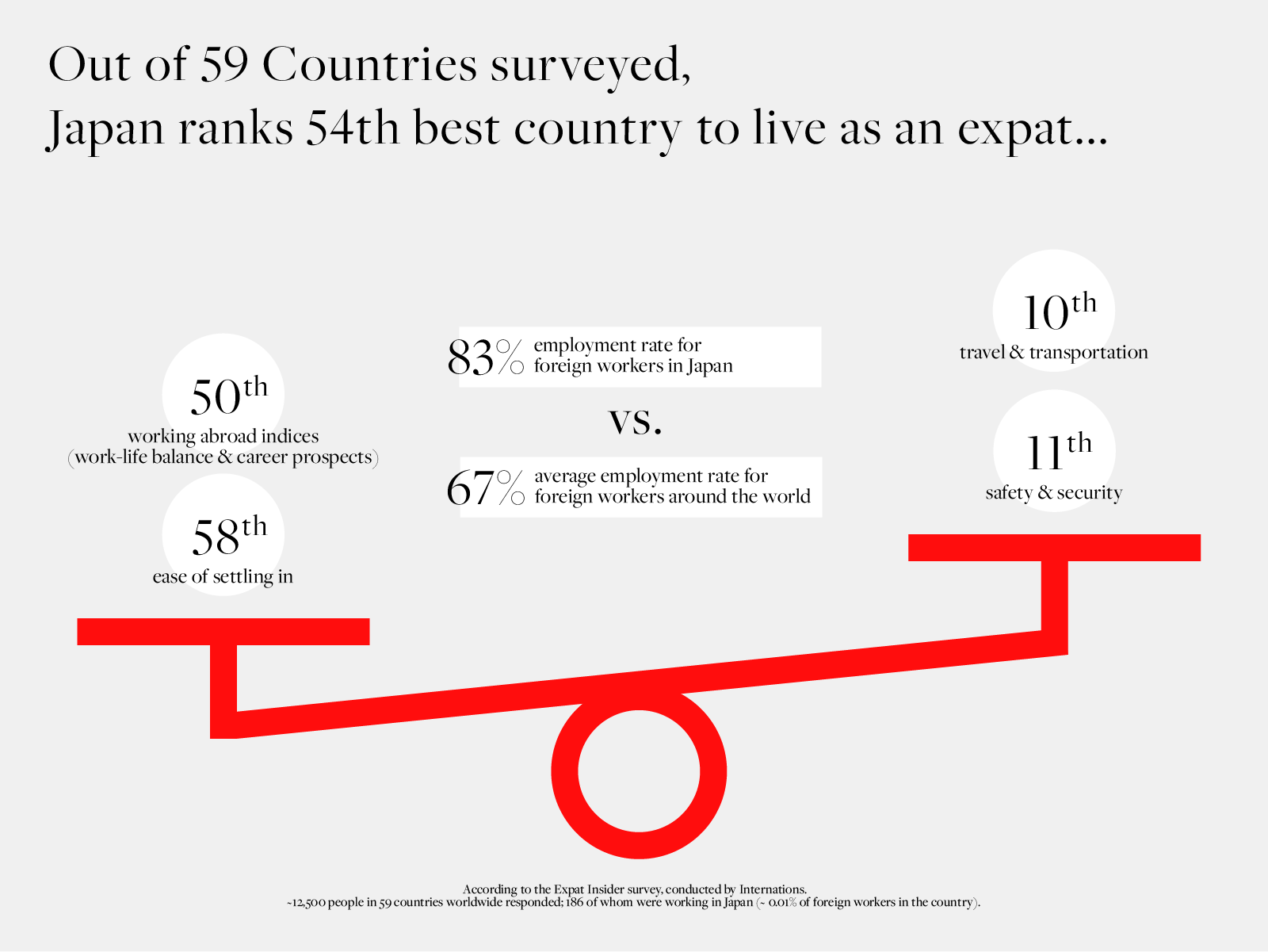

The Expat Insider survey, conducted by Internations, surveyed a considerably smaller pool of individuals. Just under 12,500 people in 59 countries worldwide responded; 186 of whom were working in Japan (around 0.01% of foreign workers in the country).

Of course, you can question the statistical significance of a survey sample size that would fit (un)comfortably onto a few carriages of the Yamanote Line, even if it covers various nationalities, job roles and income brackets. That said, some of the findings are interesting.

First, the good news: the employment rate for expats in Japan (83%) was much higher than the global average (67%), while it ranked high in Safety & Security (11th) and Travel & Transportation (10th). But Japan really struggled in the Ease of Settling In and Working Abroad indices. In the former it was 58th, topping only Kuwait. In the latter, Japan ranks 50th, due to work-life balance and career prospect issues. Japan’s overall position of 54th out of 59 is slightly anomalous, but it has yet to eclipse its middling rank of 28th (out of 64) in 2015.

It’s also worth noting some of the nations that fare better than Japan in this year’s Expat Insider survey. In 42nd place was Saudi Arabia, where women’s subservience to their male counterparts is still mandated in the national legislature. Hong Kong, in 46th place, where the locals’ much-treasured democratic values were eroded at the hands of the CCP. And Brazil (35th) and India (51st) whose combined recorded Covid-19 deaths currently outnumber Japan’s total recorded cases.

Whether or not this is an indictment of Japan or the survey, is hard to tell. So, I decided to conduct my own – rather unempirical – study on that most reliable of mediums: Facebook. Though the walls of social media tend to lend themselves better to knee-jerk vitriol than contemplative thinking, the general sentiment was largely one of balance and subjectivity: horses for courses, if you will. Interestingly, however, the truncated findings of the Expat Insider survey – “Expats feel safe in Japan but struggle with their work-life balance” – aligned with many of the responses on social media.

Why a new approach to work could save you from burnout: According to the latest research from @asana, we need a radical shift in approach to find the right work-life balance #Sponsored https://t.co/tUmOtCz6FU pic.twitter.com/Lz3pVKCNM7

— Creative Review (@CreativeReview) May 18, 2021

What Do the Surveys Tell Us?

Subjective though it all may be, there is indeed method to this survey madness. After all, humans have been diligently carrying them out since the Babylonians conducted the first census in 3,800BC. They are an interesting and hopefully representative mirror of the population’s thinking at large. Surveys can also be a nifty tool in a much bigger arsenal used to make informed decisions.

So, what, if anything, can we extrapolate from all this? That Japan’s public image paints an expat’s dream, but the reality is a little less rosy? That you’ll make a respectable wage and can walk home alone at 3 am without cause for concern, yet don’t expect to be having too many giggles on the side?

As I see it, the problem is: if you fetishize a country to the extreme – as Japan has been by hordes of foreigners (including this one writing) – you will almost certainly be disappointed in some aspects of the reality. Living in a country is more akin to a relationship; contrast and compromise; it’s a continued work in progress.

Perhaps there is also a more philosophical argument at hand: the semantic nature of the expat vs. the immigrant. The American banker and the Filipino cleaner are going to have vastly different interpretations of life anywhere. For now, however, many from both groups, and several in between, still view Japan as a desirable life-career move. Though some will struggle to acclimatize to new ways of life inside and outside the workplace, the record number of foreign workers in Japan – in spite of multiple waves of Covid-19 – suggests the storms are still worth braving.

Images by Anna Petek