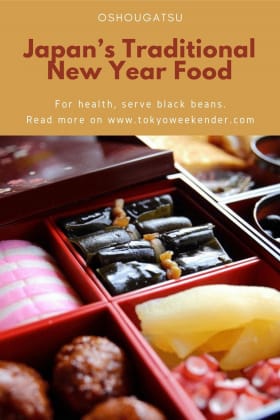

In many western countries, you’re probably likely to spend part of New Year’s Day sleeping off all the celebrating that you did the night before. But in Japan, starting off the New Year is much more about spending time with family than it is about partying. It’s a time of year when people go back to their home towns, pay their first visit to the local shrine, and sit down to some traditional food. And food doesn’t get more traditional than osechi ryori. In fact, when washoku (traditional Japanese food) was granted its status as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, the kind of food that took center stage in the description is osechi ryori.

The Story Behind Osechi

The tradition behind osechi ryori (お節料理) goes back centuries, to the Heian period (794-1185). Ritual offerings of food used to be presented to the gods on sechinichi, or days that marked the changing of the seasons according to traditional Chinese almanacs that were used during this time. The most important sechinichi, of course, was the day that marked the beginning of the New Year. On this day, special dishes were offered to various deities, and also eaten by members of courtly society.

Over the centuries, these traditions made their way to the rest of society, and by the Edo period (1603-1868), they were being practiced commonly around Japan. They combined with other beliefs, notably that on the first days of the New Year, any kind of work —including cooking — was to be avoided. There are two competing theories as to why this was the case. One was that the gods shouldn’t be disturbed by the sounds of cooking on the first days of the year, and the other is simply that the beginning of the year was meant to be a time of rest, when everyone — particularly the women of the household, who did most of the work around the home in those days — could enjoy a well deserved break.

The Hidden Meanings of Osechi Ryori’s Dishes

At the beginning, osechi was quite simple food — vegetables boiled in soy sauce and vinegar — but over the centuries, more and more types of food were added to the osechi ryori lineup, turning it into a much more elaborate affair. Almost all of these dishes have a special meaning, related either to the name of the food in Japanese or to its appearance or other special characteristics. These are some of the most commonly eaten dishes, and their associated meanings:

Kuromame (黒豆)

Black beans are meant to be a symbol of health, with the associated idea that the person will be able work hard in the year to come.

Kazunoko (数の子)

The dish is herring roe, but the symbolism is connected both the the large number of tiny eggs, and to the meaning of the Japanese words. Kazu means “number” in Japanese, and “ko” means children. The wish behind this item is that the next year will bring many children. For an extra layer of meaning, look to the name of the fish in Japanese: the word for herring is nishin, and if it’s written with an alternate set of kanji (二親), it means “two parents.”

Tazukuri (田作り)

The dish is sardines boiled in soy sauce. Historically, sardines were used to fertilize rice fields, and this word means “rice field maker” in Japanese. Symbolically, this food is eaten in the hopes that the coming year’s harvest will be plentiful.

Kohaku kamaboko (紅白かまぼこ)

Kamaboko is a kind of fish cake, and kohaku means red and white. The colors represent Japan (most easily found on the country’s flag), and are generally considered to be good luck. According to some, the red color is meant to prevent evil spirits, while white represents purity. Incidentally, Kohaku Uta Gassen is one of the most popular TV shows that people watch on New Year’s Eve, and it’s a singing competition between two teams — the white and the red.

Datemaki (top) and kurikinton (bottom)

Datemaki (伊達巻)

An omelette mixed with mashed shrimp or hanpen (fish paste). It tastes a little bit different from the tamagoyaki that you might be used to, but it’s rolled into a similar shape, which happens to look like a scroll from the side. That’s why this particular food is associated with learning and scholarship.

Kurikinton (栗きんとん)

These are sweet dumplings that are made from chestnuts. Because they’re yellow in color, they’re associated with gold, and eating them is meant to bring financial prosperity in the year to come.

Kobu(昆布)

This is a type of seaweed, and this word is closely connected to the word yorokobu, or happiness, which is what this food is meant to bring in the New Year.

Kohaku namasu (紅白なます)

A vinegared salad made with carrot and daikon. It’s pretty close to red and white in color, so it is meant to provide some of the same benefits as kohaku kamaboko.

Tai(鯛)

Sea bream; the symbolic meaning here is something of a play on words. Tai is part of the Japanese word medetai, meaning happy or joyous. This fish is often eaten on special occasions, and it’s one of the dishes that is served as okuizome, the traditional food that a baby is fed about 100 days after he or she is born. In osechi, it’s meant to bring joy and happiness in the new year.

Shrimp(海老)

The kanji for shrimp mean “old man of the sea,” playing on the sea creature’s bent back and antenna that look like whiskers. This food is meant to bring longevity.

Satoimo (里芋)

Also known as taro root, this dish is eaten in the hopes that the family will be blessed with many children — just like many small taro tubers grow off of the main tuber.

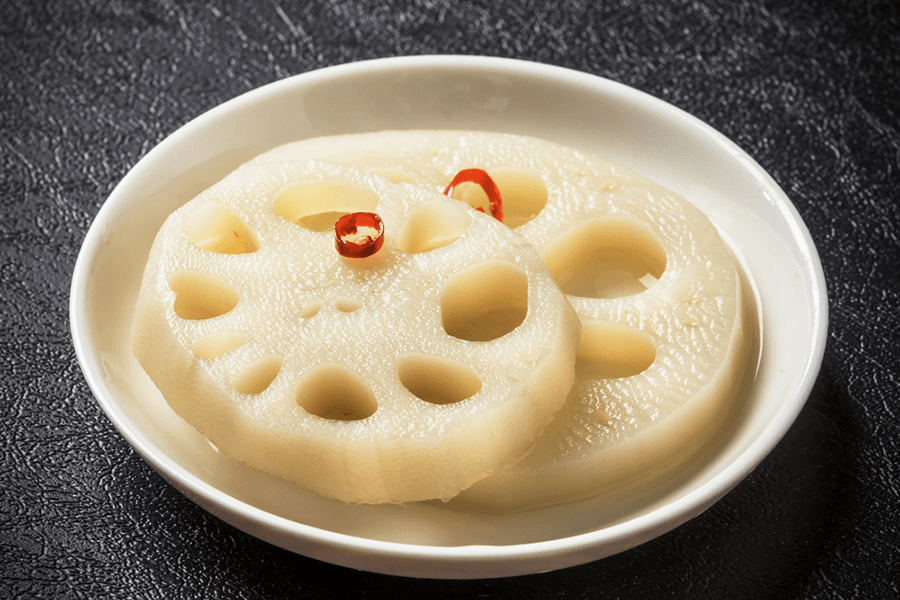

Renkon (蓮根)

Known as lotus root in English, this vegetable has very distinctive holes when it is cut in cross sections. Because you can see clearly when you look through these holes, this food is eaten in the hopes of having a future with no obstacles — or at the very least, obstacles that you can see clearly.

Kuwai (くわい)

This is an underwater plant that grows a long tuber. This long, extended shape has led to its association with having a long, steady career — no job-hopping for this delicacy!

Gobo(ごぼう)

Burdock root is a commonly eaten vegetable in Japan, and one of its characteristics is that it’s hard to cut down, and it stays firmly planted in the soil. As osechi cuisine, it’s meant to impart strength and stability.

Zoni(雑煮)

A simple soup, flavored with dashi (a stock made from bonito and/or seaweed) in eastern Japan and with miso in the Kansai area, served with chewy pieces of mochi (rice cakes).

Toshikoshi Soba (蕎麦)

When soba is eaten on New Year’s Eve, it is known as toshikoshi soba (年越し蕎麦), and it is meant to bring the eater a long, fine life – just like the shape of the soba itself.

Just as it goes with any tradition, not every dish is eaten at every household, and some dishes lose favor over time – sometimes because younger people don’t particularly enjoy eating them, or because tastes change. (One newish item that you’ll find in osechi ryori spreads, although it doesn’t have any special meaning yet, is roast beef.) The osechi dishes, aside from the zoni and the soba, are served in elegant lacquer boxes known as jubako.

Some families prepare the osechi themselves, while others choose to order theirs from department stores or convenience stores. Although it might be a little late to learn how to make the items yourself this year, these cooking classes offer students the opportunity to whip up their own osechi. For those who wish to purchase a beautifully crafted osechi for their New Year’s celebrations, department stores like Takashimaya and Keio stores offer fantastic options — though they certainly don’t come cheap!

So if you have a bit of osechi coming to you in the New Year, here’s hoping that you understand it a little better, and might even be inspired to try to make some yourself in the years to come!

This article was originally written in Alec Jordan in 2017 and updated in December 2020.