Japanese poetry is how I first became interested in Japan. It pulled me away from Baudelaire’s Le Spleen de Paris and helped me discover an array of books and amazing authors, from classic reads to more contemporary ones. On many occasions, when I express my affinity towards Japanese poetry, my interlocutor immediately responds: “Haiku?” Though I’m always left a little bit disappointed by this assumption, I can’t hold it against them. Haiku is often the only image of Japanese poetry that people know so of course, it makes sense that that’s where their mind goes first.

Much like the rest of Japanese literature, the history of poetry in the country is unclear and often genre and subgenres were classified posthumously, sometimes even centuries later. This article goes more in-depth into the history of Japanese poetry, so I’ll spare the read to those who simply are curious to know about the different kinds of Japanese poetry.

Note: In Japanese, the common poetic measurement is morae. While similar, linguistically a mora is not equivalent to an English syllable. This is why haiku translations, for example, don’t follow the 5-7-5 structure.

Kanshi

Kanshi refers to works by Japanese poets written in classical Chinese following a form that reached peak popularity under the Tang Dynasty. During the Heian Era (794-1185), Chinese was the language of courts in Japan. Until then, literature was spoken or sung; poetry, like folklore, was shared and passed down through oral tradition in various forms of waka (more on waka below).

Kanshi was then often practiced and enjoyed only by aristocrats. Though Japan went through a few different political systems, the form remained popular throughout Japanese history, especially among academics and intellectuals. A few notable poets include Kukai, Sugawara no Michizane, Maresuke Nogi and uber-famous writer Natsume Soseki.

So how do you write a kanshi poem? Well, it’s actually quite technical. There are no particular restrictions when it comes to theme, meaning you could write about anything that suits your fancy. However, a good kanshi relies imperatively on the structure. Poets have to conform to the form (lüshi) and rhyming patterns. There are many variations, but the most common is composed of four or eight lines, each written with five to seven morae. In addition to a strict composition, writers had to pay close attention to rhyme scheme, which they had to achieve based on Mandarin tones.

Waka

Contemporary to the kanshi but also standing at its polar opposite is waka. This classic poetry was written in Japanese and is said to have been around considerably longer than kanshi. While the latter was thought to be of higher status due to its language restriction, waka came to be a relatively accessible art. This is not to say that it also wasn’t loved by the people of the court. Among the many forms that waka encompasses — the longer the history, the more shapes poetry takes — the two better-known forms are choka and tanka.

Choka tend to be long poems, said to have no restrictions to length and are therefore often compared to Greek epics. Its structure is pretty simple, consisting of a couple of phrases of five and seven morae (repeated as needed) and ends with the last group of three phrases respectively five, seven and seven morae.

Tanka follow similar a structure but are considerably shorter, often only consisting of five groups of words of five, seven, five, seven and, finally, seven morae respectively. When translated, tanka tend to become a single sentence.

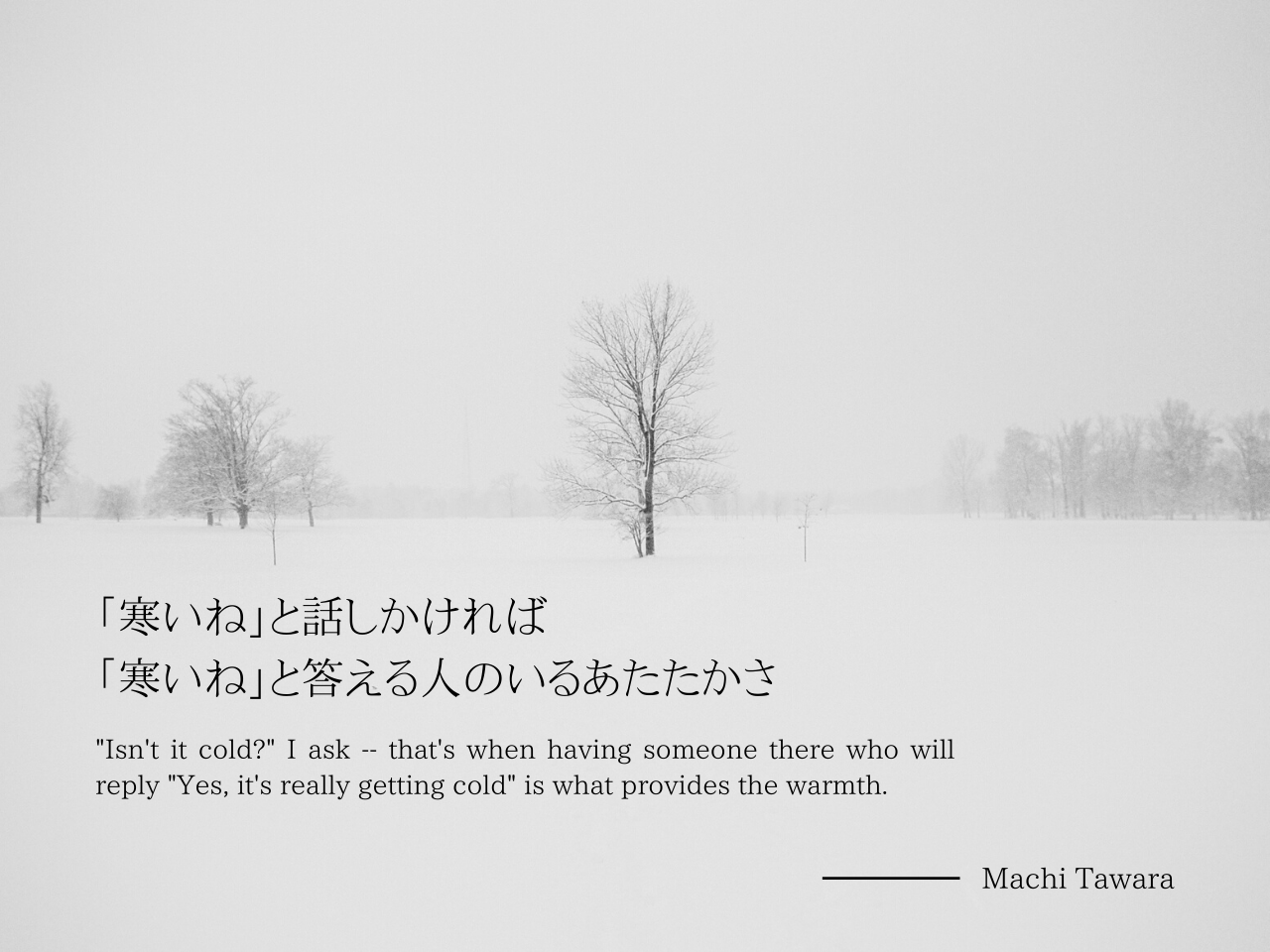

The above tanka is a spring-inspired poem by Machi Tawara, one of Japan’s most popular contemporary tanka poets. Tanka is still popular in modern Japan. You’ll notice that unlike kanshi, waka doesn’t abide by any rhyming rules, which later came to influence modern songwriting in Japan in all its forms.

As shorter poetry became the preferred form, the choka was phased out by Japanese poets and “waka” came to refer specifically to tanka.

Haiku

The haiku is the most popular form of Japanese poetry outside of Japan, and also the most accessible. It was originally a derivative of a hokku, the opening part of a range, a form of collaborative poetry, but the haiku soon became a favorite among poets. Its 5-7-5 structure has defined the Japanese literature landscape while introducing it to the world.

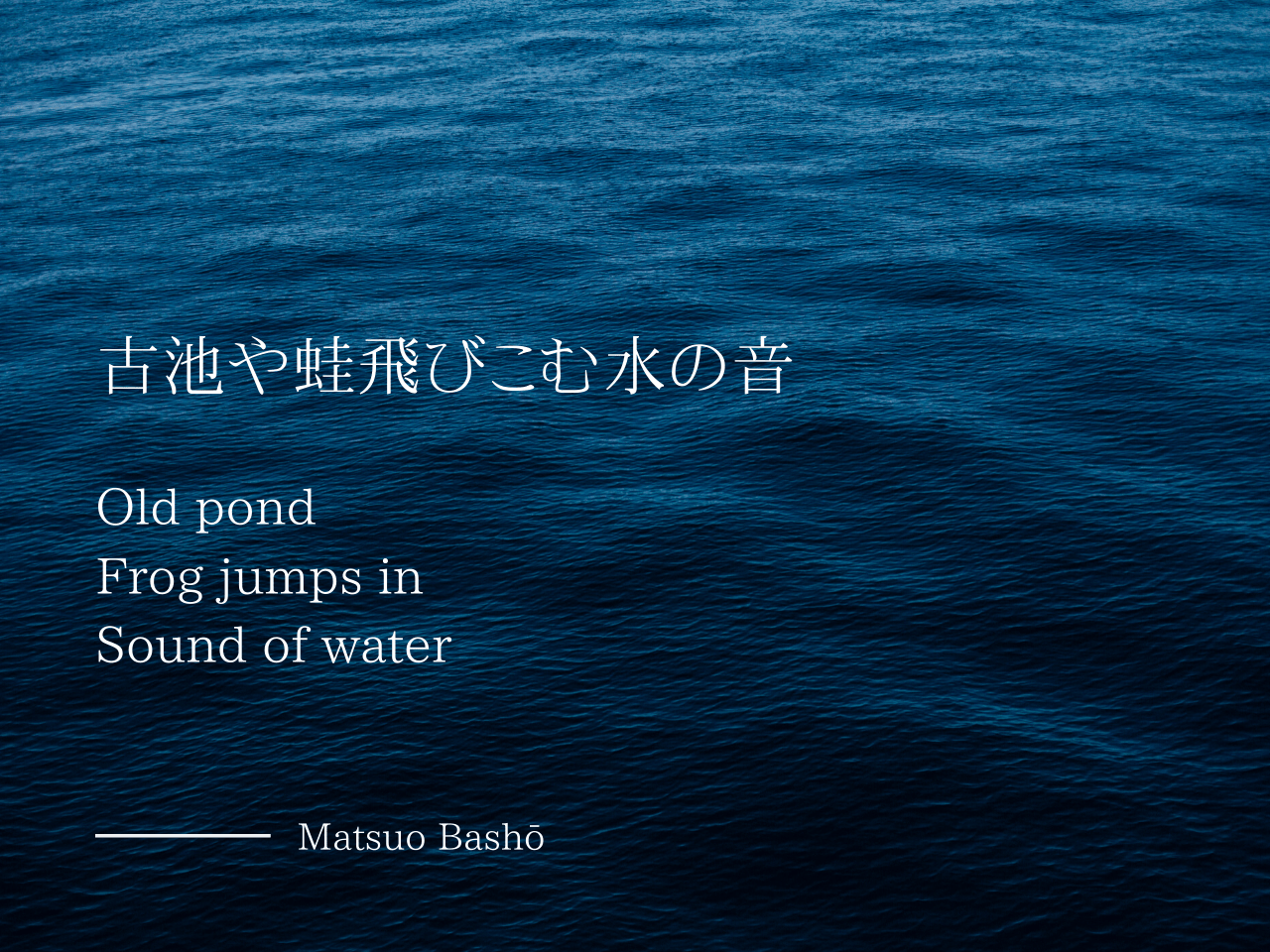

In the spring of 1686, classic poet Matsuo Basho wrote one of the world’s best-known poems:

To write a haiku means to master a strict set of rules that goes beyond its set number of morae, which has of course been broken every now and again. Each line has an assigned role to create the defining flow to the poem and reflects the philosophy behind the haiku: the beauty of a single moment. A haiku also implies a complex use of kireji. These words or expressions often referred to as “cutting words” offers either a satisfying end to the poem or a clean break between two ideas.

Haiku rely on imagery pulled from and inspired by nature. Read some of our favorite Japanese island-inspired haiku.

Today, the haiku is still a popular format often explored by writers all over the world. The constricted amount of words has for a long time been a welcoming challenge for English poets.