When the first section of Yamanote Line was built in 1885 it served as a freight line that connected Shinagawa and Akabane stations, completing the route that led all the way from Yokohama to Aomori in the far north. The new C-shaped route ran through Tokyo’s western foothills (yama-no-te) where there was less populous to disturb.

The ever-expanding city soon encroached into the sleepy villas of Meguro, Shibuya and Shinjuku and in 1925 the 35-kilometer Yamanote loop was completed, transitioning into one of the most important passenger lines in Tokyo, if not the world. More than four million people ride the line daily. Residences along the Yamanote Line come at a premium price due to the convenience. People run ultramarathons along the entire route.

“What’s really funny about the Yamanote Line is that people take it from home to another place for work, but it’s not often they really visit”

Thus when Tokyo-based Swiss graphic designers Julien Mercier and Julien Wulff sought a chance to break away from the creative constraints of their day jobs, they were lured to the green-striped trains of the Yamanote Line.

“In Switzerland we have a strong image of trains. Public transportation is quite popular [there], so it’s probably what influenced us to follow a train line,” says Wulff. “What’s really funny about the Yamanote Line is that people take it from home to another place for work, but it’s not often they really visit.”

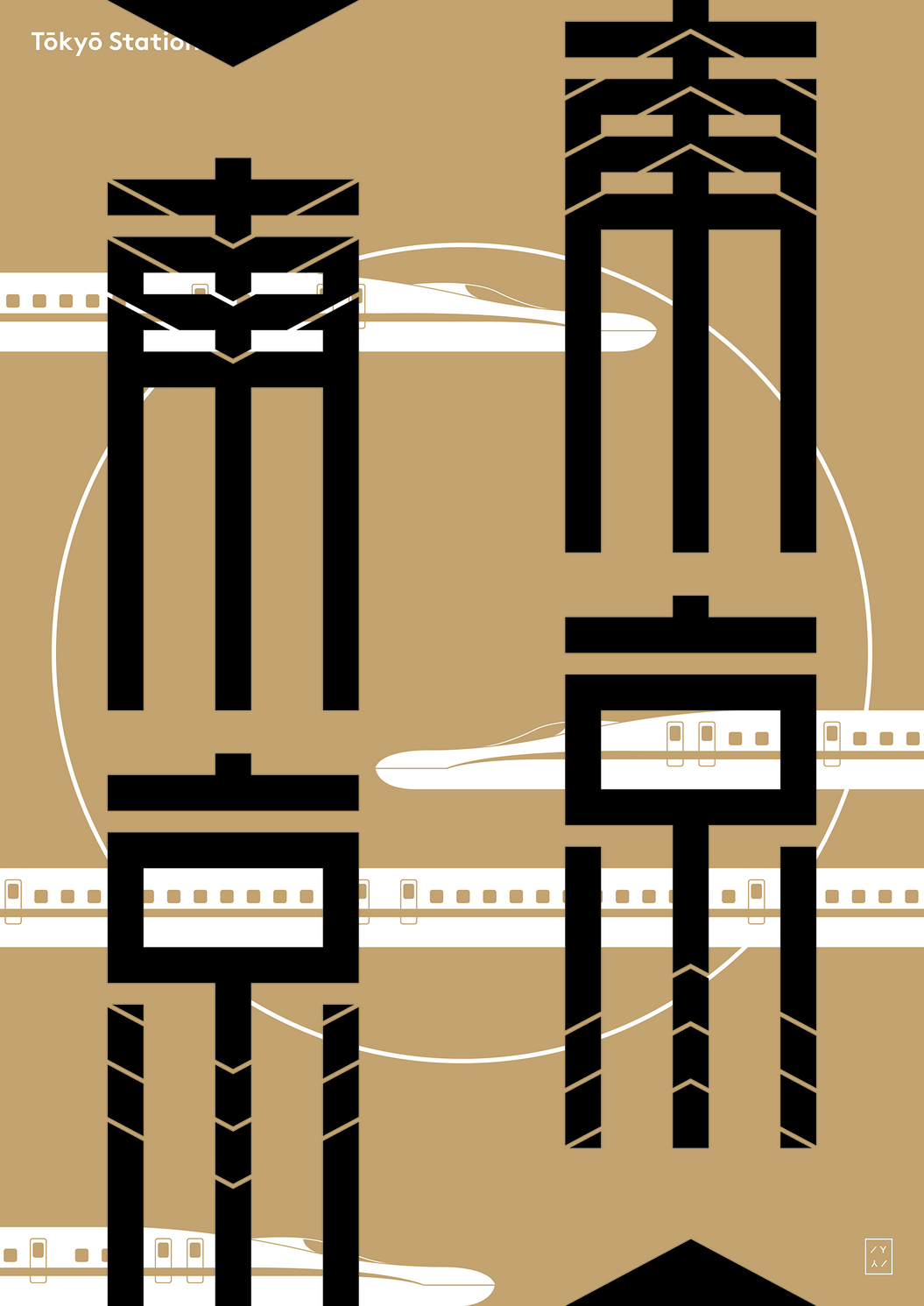

Four years ago the two began to work on what eventually evolved into the YamanoteYamanote exhibition series. Each designer creates a poster for each station on the train line that represents their parallel perspective, and then they organize local pop-up exhibitions at carefully selected venues near that station.

With the concept “one station, two posters,” the dazzling designs draw on everything from pop culture to typography in order to break apart and rearrange what makes each stop special. Even though they walk the same streets, Mercier and Wulff create their own interpretation of the stations in their minds, ready to be brought to life.

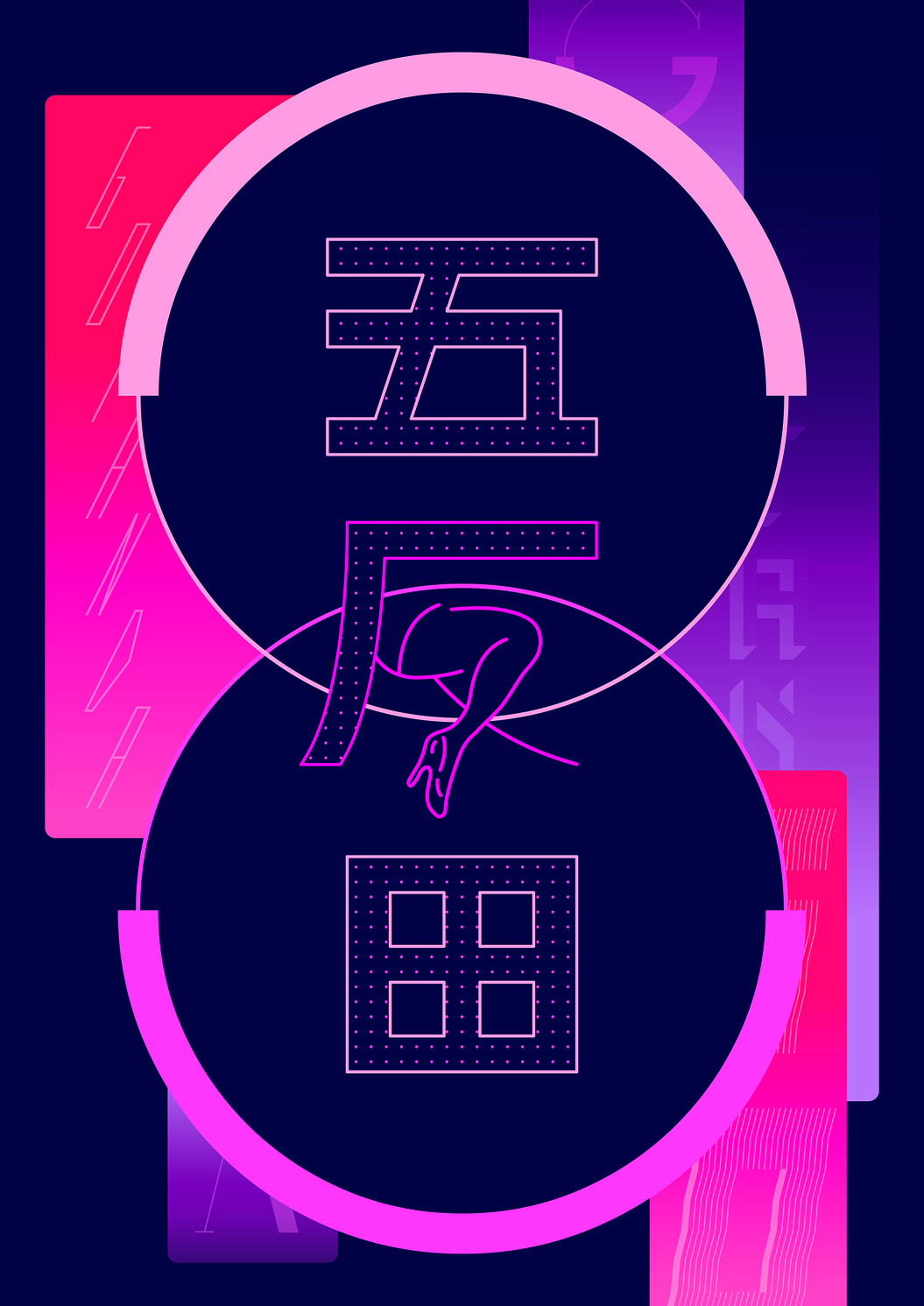

Mercier’s posters showcase his signature blend of Swiss typography and Japanese kanji.

“I think there is always something interesting to play around with, from the name of the station and the meaning of its kanji,” he says

While he also likes to use typography in his work, Wulff’s pieces are representative of his multidisciplinary design background, particularly in illustration and print design, with character and color forming the brunt of his creative backbone.

“It’s a very free project. We’re not trying to meet some guideline”

The parallels in visions are distinct, as the concept for Mercier’s Shibuya poster is a futuristic evocation of the vivid cityscape at night as depicted through kanji made with acrylic plates. Meanwhile Wulff’s Shibuya poster is stark black and white pair of shoes, showing the treadmarks of one to represent the famed Shibuya crossing.

“We create the poster in the function of our creativity,” Wulff says. “It’s a very free project. We’re not trying to meet some guideline.”

As such, each exhibition is a practice in improvisational planning, starting with the duo traveling to the respective station and exploring around. They may have a few venue recommendations from friends, but it’s just as likely that they’re left to their own devices.

The first exhibition was held at Akihabara at Game Bar A-Button on July 1, 2016. In late February they completed their 29th exhibition at Okachimachi Station. The final YamanoteYamanote exhibition will be held at the new Takanawa Gateway Station.

Built to help meet the demands of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, the station is scheduled to open on March 14, 2020. The date and location for YamanoteYamanote’s final show has yet to be announced.

While their Ikebukuro Station exhibition led to a night of bowling, the duo have found nice surprises at lesser-known destinations. They contacted a local family-run theatre ahead of their July exhibition near Tabata Station and seized the opportunity to set up a small crew to film a mini-documentary about the poster production process. The documentary then aired during the exhibition.

At another exhibition the two were able to book a printing shop where they were able to print posters and T-shirts fresh on the spot, allowing some of their more dedicated followers to take home a memento of the journey.

“The visitors at each of the minor stations are very surprised and happy,” says Wulff. “Even some Japanese people come to us at exhibitions and thank us for showing them an area they wouldn’t have visited otherwise.”

Throughout the process, the project grew bigger, as did their following. As they’ve run through the various parts of town, locals have tended to follow the two throughout their stations and Mercier notes that they have been able to get to know quite a few people along the way.

Even if people might trail off after three or four stations, new eyes are always coming to form connections, and the locals they meet have even helped the duo find unique venues that show off the distinct character of each neighborhood.

At the Nishi-Nippori exhibition in September, the Sampota Cafe welcomed them in for the local Yanaka Hatsune festival, during which they got to share both food and cultural festivities with guests. This followed another successful pop-up event during which the project returned to Shibuya to announce its online store, as well as new T-shirt and poster designs.

Fast-approaching their final stop, Mercier and Wulff want to put on one last showcase for all the stations.

“Sometimes as a joke we say ‘how about another round of the Yamanote line,’” says Wulff. “We’ll see what’s next on the horizon when we’re finished.”

Find Mercier and Wulff at yamanoteyamanote.com and on Instagram at @yamanoteyamanote

Words by Carter Diggs and Nick Narigon