She was a pleasant looking woman. Dressed in white pants and a bright yellow blazer, she appeared slightly younger than her 82 years. She spoke with feeling and passion, and often with her hands, a trait, perhaps, more commonly associated with Italian grandmothers than elderly Japanese women. And though her words were relayed through an interpreter, her emotions did not require any translation.

By Gary Malone

Seiko Ikeda is what they call a “hibakusha,” a survivor of the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. She was just 13 years old when the Enola Gay flew its unprecedented mission over Hiroshima, but she still carries both physical and emotional scars from that day. And on this sunny August afternoon, in a conference room at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, she sits just a few feet across the table, sharing her amazing story with my wife and me, a pair of New York City public school teachers spending a part of our summer break learning things we could never get from a text book.

My wife Amber and I are teachers at Daniel Carter Beard Junior High School 189 in the Flushing section of Queens, New York. Sharing a passion for both education and travel, we hit the jackpot when we learned about Fund For Teachers, an organization that provides grants for teachers looking to travel to conduct research in order to better their classroom practices.

Once we decided that we would apply for a grant, we just needed to figure out where we would go and what we would study. It didn’t take long for us to decide on Japan. Being that Amber’s sister and her family have been living in Tokyo for the past ten years, Japan was a place we’d visited quite a few times and shared a fondness for. We decided that our trip to Japan would focus on the World War II bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As both students and teachers, we had always looked at WWII from the American viewpoint, so we wanted to explore how the war, and specifically the atomic bombings of these two cities, were taught, perceived, and remembered in Japan.

Through a connection in Tokyo, we linked up with Naoko Koizumi, who would serve as our interpreter in Hiroshima. Luckily for us, she provided much more than just her translation skills. In addition to interpreting our interview with Seiko Ikeda, Naoko also put us in touch with her friend Tomoko Watanabe, a producer of White Light/Black Rain, a documentary about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that aired on HBO. On August 6, we went to meet with her at her Hiroshima office. Ms. Watanabe had previously reached out to some of her teacher friends and arranged for them to meet with us. For two hours we spoke with a group of 10 Hiroshima teachers.

They shared with us their experiences in teaching about the war and the bombings and their focus on what is called “peace education.” They explained how in their elementary school classrooms, students learned about the bombings through children’s books and often folded paper cranes to be brought to the Peace Museum. The focus was placed on the horror of the bombings, and how that should teach us not to harm others.

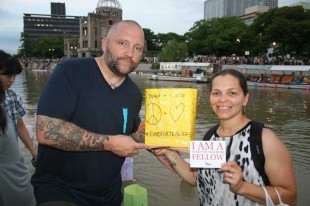

The evening of August 6 was probably one of the more memorable parts of our journey. That night, we attended the memorial festivities at Peace Park. It was an amazingly serene scene as candles created by school children covered the ground, outlining the A-Bomb Dome. It seemed to be very family-oriented, as young kids could be seen walking hand-in-hand with their parents. The highlight of the night was creating our own paper lantern and floating it down the Motoyasu River. Sitting along the riverbank with our own children and watching the hundreds of colorful lanterns float peacefully away was an experience we will always remember.

The following day, Naoko put us in touch with Yumi Kanazaki, who oversees a young writers program at a Hiroshima newspaper called Chugoku Shimbun. At the newspaper’s offices, we met with a group of these young writers and discussed their experiences learning about WWII in school. We were told that any real details about the war were not discussed until the latter part of middle school. Pearl Harbor, for example, was something they’d heard of, but not something they knew much about at all. One girl had explained to me that her perception was that Americans viewed the bombings as a major accomplishment, something we were proud of. That caught me a bit off guard. I have never thought of the bombings in that way, and I doubt many Americans do. But to be honest, I probably never gave the bombings that much thought. The WWII that I learned about in school was more about America’s defeat of Hitler and the Nazis. What happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was an afterthought. Or at least that’s the way it was presented to me.

After three non-stop days in Hiroshima, we boarded a train and headed for Nagasaki. Just as in Hiroshima, we were able to be present for the anniversary of the bombing and attended the ceremony in Nagasaki Peace Park on August 9. The ceremony was highlighted by a touching performance by the children’s choir. Afterwards, we visited the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb museum. Unfortunately, an interview we had originally set up with a survivor of the Nagasaki bombing was cancelled at the last minute. Despite that, we still enjoyed our time in Nagasaki and feel it was a valuable part of our trip.

Back in Tokyo, we spent some time visiting shrines and museums, as well as conducting interviews with various people to discuss their experiences of learning about WWII as students in Japan. One of the more interesting places we visited was the Yushukan War Memorial Museum. The museum is fairly large, and the exhibits are arranged in a sort of timeline, detailing the long history of Japan’s conflicts. The narrative put forth at the museum is one quite different than the American version of events. According to the WWII related-exhibits, the US basically starved Japan of resources in a calculated move to force Japan into throwing the first punch, so to speak, in order to justify entering the war.

With the help of my sister-in-law Mica and her husband, James, we were able to arrange some interviews with friends and colleagues of theirs who had been educated in Japan. Throughout our interviews, we discovered that each person we spoke with had a different experience in learning about the war. Yuko, one of James’s coworkers, is the product of an American father and a Japanese mother. “Many teachers had animosity towards America and presented Japan as the victim in the war,” she explained. She went on to say that she learned about much of Japan’s military aggression from her mother, and not from her school.

Ai, a friend of Mica’s, was raised mostly in Japan, but spent part of her high school years in Pennsylvania. She had this to say: “In the United States, we learned more details: kamikaze pilots, Pearl Harbor, Okinawa. I was shocked because it [the dropping of the atomic bomb] was taught like it was the last resort and it had to be done.”

One of the last people we interviewed was Mayumi, another of James’s coworkers. Mayumi explained how she attended an alternative school, where one of her teachers—a self-described communist—scoffed at the idea of Japan being a victim and would routinely discuss the atrocities committed by the Japanese military. But during our discussion, she recalled a memorable lesson she had taken part in as a middle school student. As she explained it, the teacher had divided the class into groups of four. At each group a candle was lit and the students were asked to write down a description of what they observed. As they shared their descriptions, they began to notice although they were all describing the exact same incident, their accounts were all a little bit different. “This is history,” the teacher explained. That story really resonated and basically summed up the point of our whole trip: History is not his story; it is our story. And it is up to us to tell it.

Unless noted, photos courtesy of Gary Malone.