Richard Lloyd Parry has had a front row seat on one of the biggest stories to jointly grip the British and Japanese press over the past 10 years: Lucie Blackman’s disappearance and the subsequent trial of her accused killer, Joji Obara. If you spent any time in Tokyo in the last decade, you would have come across newspaper and magazine accounts of the case, and quite possibly met one of the many people who were tragically swept up in its wake. Filled with drama and mystery, the story was ripe for people to put forward opinions and theories, but at its center, in the form of the serial rapist Obara, was the unknowable. Now, the Tokyo-based journalist has released his definitive take on one of the most gruesome crimes that the modern Japanese police force has ever had to tackle

by DONALD EUBANK

“Almost everything in this case, it’s almost as if it was calculated to cause maximum damage to the people left behind,” says author Richard Lloyd Parry at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan earlier this month. “Joji Obara’s character and demeanor is one of the elements of that. He never admitted a thing. It wasn’t a matter of not saying sorry, he denied consistently throughout that he had done anything wrong at all. Even with all these videos which he had in all these cases, except for Lucie’s.”

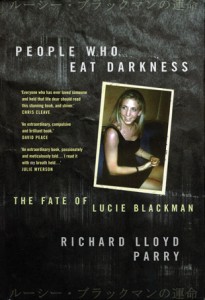

When we spoke, Parry was just about to set off to England to promote the UK launch of “People Who Eat Darkness”, his comprehensive account of all the unexpected paths that the investigation of the Lucie Blackman case took him down, and the agony that it caused all involved, save Joji Obara. In the new book, the veteran journalist presents in depth each of the elements of the case that contributed to this lingering damage, from the seven months when neither her whereabouts nor the reason for her disappearance could be determined to the police incompetence that was the reason for this delay; from the complicated relationship between her parents Jane and Tim to the host of characters and dead-end leads that were players in the tale.

Currently the Asia editor of the British newspaper The Times, Parry covered the story from the start, just after Blackman, a former British Airway flight attendant, went out for a Saturday drive on July 1, 2000 with one of her customers at a Roppongi hostess club and never returned. Her body was found nearly seven months later, dismembered and buried in a shallow seaside cave on the Miura Peninsula, after a wealthy, aimless question mark of a man who was suspected of being responsible for her disappearance was arrested in a dingy apartment near the club in October 2000.

Obara was given a life sentence for the rape of eight women and the rape and death of one more in his first trial, but acquitted of charges stemming from Blackman’s disappearance. In an appeal that that came to its conclusion in 2008, the original charges were upheld, and he was additionally convicted of the kidnapping, dismemberment and disposal of the body of Lucie Blackman, but not of her murder. With a final appeal to the Japanese Supreme, the case dragged on until lasted till December last year, and Parry continued to cover it, meeting not only all those who were immediately involved, including family and friends of the victim, but also with the few people who could tell him about the mysterious man who was accused of perpetrating the crime but had surprisingly been acquitted.

“One of the most striking thing about doing this research was how difficult it was to find out anything about Obara and his family. It was almost as if they went through life erasing the traces they left behind,” says Parry. “I went to Osaka a couple of times and … spent a lot of time looking into him and his family and his past, and I also talked to half a dozen Japanese shukan shi reporters, hard-nosed tabloid hacks who had been mobilized as soon as Joji Obara had been arrested in 2000 to dig into his past. These are guys who are extremely experienced and good at doing this kind of thing, and they all said that it was almost uniquely difficult to find anything about him.”

“They said that often when someone is arrested, the family will be reluctant to talk, which is not surprising, but you can always find someone who will talk. But here, there was no one.”

Lucie Blackman’s father Tim talks with Japanese press on April 23, 2007 after members of the family paid their respects by visiting the cave on Aburatsubo beach where her dismembered body was found. Her accused killer, Joji Obara, had just been acquitted of her death in a trial that found him guilty of the rape of eight women and the rape and death of Carita Ridgeway. JEREMY SUTTON-HIBBERT PHOTO

From the other side, Lucie Blackman’s, Parry had plenty to go on from the beginning. A week after she was reported missing by her roommate, Louise Phillips, Lucie’s sister Sophie Blackman came out to start a search effort, to be quickly followed by their father, Tim Blackman. Sophie and Tim immediately engaged with the media, providing them full access to anything that they wanted to know after their first disappointing meetings with the Japanese police, in order to make sure that the case was followed up.

“Tim made the conscious decision early on to establish close contact with journalists and to use the media to keep the case in the spotlight and to use the media as a form of pressure on the police,” says Parry. “And in doing that, he alienated the police, and his personal relations with them was poor. If he had not chosen to do that, however, if he had kept mum and done as he was told, I don’t think he would have really have learned anything more about what happened.”

One of Parry’s reoccurring themes in the book is a powerful critique of the Japanese police and their almost mind-bendingly poor response to not only the seriously suspicious circumstances surrounding Lucie Blackman’s disappearance, but to the fraught emotional state of the victim’s family members, and most damningly, to previous reports of Obara’s predatory behavior that could have prevented the whole fiasco and saved a staggering number of women from the violations that Obara perpetrated on them. When he was finally arrested, it quickly became clear that he had sexually attacked more than 200 woman after police found the rapist’s own collection of 209 home videos that he had filmed of himself having sex with drugged and senseless victims and his egocentric diary entries that detailed the dates, places and varying cocktails of drugs used on each one.

Parry believes that although the police had so many signs pointing them the right direction before the Blackman case and during it, and that they still took so long to capture such a prolific repeat offender, shows a real weakness in their ability to think creatively when presented with cases that don’t fit the norm or happened outside of proper society.

Parry believes that although the police had so many signs pointing them the right direction before the Blackman case and during it, and that they still took so long to capture such a prolific repeat offender, shows a real weakness in their ability to think creatively when presented with cases that don’t fit the norm or happened outside of proper society.

“The strongest reproach against the Japanese police was not that they had reacted slowly when she had gone missing. Because she was just a girl who had gone missing, and any police force would have given it a few days. Most of the time people show up. They have gotten drunk, or run away with someone or fallen out with their friends,” says Parry. “The biggest mistake they made was in 1992, when they didn’t cotton on to the suspicious circumstances surrounding Carita’s death. Because that was highly suspicious. And there were other reports.”

Carita Ridgway was an Australian hostess who had died almost 10 years before Lucie Blackman in 1992 after she had been admitted to a hospital by someone calling themselves Akira Nishida. The trial showed that “Mr. Nishida”, who said that Ridgway had suffered food poisoning after eating a bad oyster, was Joji Obara. When the prosecution was preparing their case against Obara, new investigations revealed that she had died from liver failure that was consistent with poisoning from an excess of chloroform. But the police had never taken her family’s pleas to look into her death seriously, and this was probably due to her occupation.

“My impression is that they deal in stereotypes, and hostesses are regarded as intrinsically unreliable and compromised, certainly in any kind of sexual crime,” Parry says when asked about the police’s complacency. “No policemen ever said that to me. I got this impression from conversations with other people, including experienced Japanese journalists. If a hostess comes forward and says, ‘I have been sexually assaulted in some way,’ the attitude is often, ‘Well, what did you expect?’“

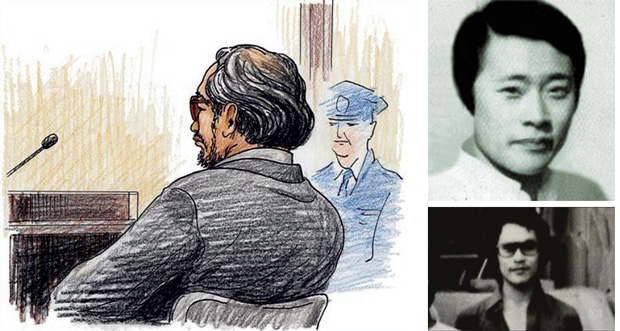

Some of the few existing photographs and court sketches of Lucie Blackman’s accused killer Joji Obara COURTESY OF RANDOM HOUSE

Obara used multiple names over the years, and the one that he was tried under was only his because he chose it when changing his nationality from South Korean to Japanese in 1971. His parents were Zainichi immigrants — “impermanent” Japanese residents from Korea — who became remarkably wealthy in Osaka after World War II through taxi companies, pachinko parlors and parking garages. He was born Kim Sung Jong, a name that was changed to Seisho Kin as the family rose in prominence in Osaka and then the more Japanized Seisho Hoshiyama before he was sent by his parents to live alone in the upscale neighborhood of Denenchofu at age 15 while attending Keio University’s prestigious high school in Tokyo.

Parry delves as deep as he can into this history, exploring the conditions of the Zainichi ethnic Koreans in Japan, who were no longer citizens of their own country and yet second-class citizens in the country that was the home of their second generation. Despite the Kim family’s wealth, there was always a glass ceiling that no Zainichi could transcend at the time, an invisible racism would keep them out of the mainstream of Japanese society.

But even this background, and whatever strange family dynamics might have existed — Parry reports that Obara’s older brother appears to have been mentally disturbed and his father died under mysterious circumstances during a trip to Hong Kong — can not explain the perverse turn his life took, shut off from other humans outside of his closely controlled interactions with woman whose time he paid for and then abused.

“I was aware that it is very easy to play Doctor Freud. There are suggestive things about his background and past that we know about him: the immigrant parents, the sudden rise from poverty to wealth and the dislocation that brings, the physical dislocation when he left his home as a child in Osaka, living as a rich teen with no adult supervision,” says Parry. “You could look at all of those things and say ‘Ah ha, this is why his personality became distorted.’” But lots of people suffer these dislocations and don’t become serial rapists.”

The most telling thing about his personality was his seeming isolation from the society around him.

“For me, the question that I never answered to my satisfaction was whether Obara had any friends,” says Parry. “I talked to a number of people who knew him from his school in Osaka and Keio School, and from university, but none of them unambiguously described him as a friend. And one of his lawyers said to me that he thought that he lacked friends.”

Though Parry is thorough in tracking down whatever leads he can find, in the end Obara and his wiped-out history are beyond his reach. The killer appears in only a handful of known photos and even when he appeared in court on trial, he made great efforts to sit such that people who attended would never get a full look at his face. There is no one who appears to know him after his time in school, and how he filled his days when he wasn’t assaulting his victims is impossible to determine. The man responsible for so much unhappiness is a void in time.

“When I started out, I was expecting to crack Joji Obara like a nut, and I guess I imagined it like a puzzle, like if I succeeded that I would find a solution for it. There would be a secret,” says Parry. “But I don’t think there is. And perhaps for people like that, the secret is that there is nothing there, that what explains his behavior is not any kind of positive evil, to use that problematic word, but a lack of capacity to make any kind of human relationships.”

In the convenient yet gory tales of Hollywood and pulp serial killers, we are typically given some clue, some way in to understanding the gruesome acts of their central characters. But Parry found with a case like Obara’s — a real world case — that maybe there never is a real world explanation. Given the standard storyline, this could be a source of infinite frustration, but as presented in “People Who Eat Darkness”, it feels like a corrective to all the narratives that have been fed to the public saying that we can find the answer. That Parry refuses to contort himself and the narrative out of shape in the service of finding one — that wouldn’t necessarily be a true one — is the real strength of the book, and suggests a new way forward, perhaps, for nonfiction and fiction alike: That there are some things, despite all our studies of psychology, history, morality, philosophy, that are unknowable and cannot be neatly summed up.

In the end, Parry describes Obara in the book as being all surface, saying that we can only know him by the misery that he has caused. This lack of depth become his definition.

“There is a whole literature about serial killers and psychopaths. I hesitate to use that word, and no psychiatric evaluation has ever been made of him, so I don’t know whether the word psychopath means anything very much or whether it applies to him,” says Parry. “But one of the things that is often said of people who are labeled as a psychopath is that they are very boring. There is very little to say about them except to describe their actions, they lack personality really, because they don’t have empathy and they don’t form relationships.”

“And if you strip relations away from human beings, then what is there left really, except for just biological drives? So in the end, I stopped worrying that he didn’t seem very interesting, and thought that might be the most interesting thing about him.”

An altar in front of the cave near Tokyo on Miura Peninsula where the remains of Lucy Blackman were found on Feb. 8, 2001 JEREMY SUTTON-HIBBERT PHOTO

The depth of Parry’s account of the Blackman case is due to the refusal of Obara to admit any kind of guilt, giving prosecutors years to dredge up information. As well, over the case’s 10-year duration, a host of other people introduced themselves into the narrative, including conman Mike Hills, who could have been sent from Central Casting for a role in a Guy Ritchie movie; the bickering Tokyo sadomasochists; and the racist club owner Kai Miyazaki. Parry himself goes undercover as a barman (“I discovered by that time, 2007, there were fewer of those bars. [Tokyo Governor Shintaro] Ishihara had done his sweep of Roppongi.”), was unsuccessfully sued for libel by Obara (“We have published “People Who Eat Darkness” under the assumption that he would sue us.”) and mistakenly received a package intended for Tokyo’s noisy rightwingers, inciting them to “deal with” him for “insulting the Imperial family”. Whether it was directed by Obara, he never found out.

The Blackman family, who cooperated completely with Parry in his writing of the book, are given a full and fair treatment. Unwilling to play the typical beaten-down victim, Tim, who is divorced from Jane, was lambasted by the British press when he accepted an offer of “consolation money” totaling almost half a million pounds from Obara’s lawyers. Parry tries to cut through all the name calling.

“What I wanted to convey was the extent which they all suffered, and that they are victims of a terrible crime. That seems like stating the obvious, but it really was forgotten in a lot of the vituperation against Tim when he took the money,” Parry says. “It was almost as if he was a criminal in some of the things you read, and he’s not. He is a human being who found himself in a terrible situation and made a judgement.”

After all, the criminal was Obara, the man-shaped hole in a story that blighted everyone left behind, a story that Parry tells with sensitivity and intelligence, giving Lucie Blackman’s life at least some semblance of meaning and peace in the end.

External Link:

Richard Lloyd Parry, Wikipedia