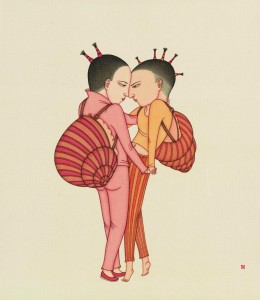

Snails, Wilson Shieh

They happen in Tokyo, too: those rare occasions when there are no shows that I can cover, because for whatever unserendipitous reason, all of the exhibitions I haven’t seen are ending in the same weekend, or are simply not something I’m interested in.

That was more or less the situation on my recent visit to Hong Kong. I consulted the ArtIt calendar, my favoured method of finding out upcoming shows in Tokyo, and found a grand total of three — count ’em, three! — shows of contemporary art going on in all of Hong Kong. “Well this can’t be right,” I said to myself, and just to test it, put in a date two weeks earlier than my trip. It came up with a page and a half of exhibitions.

So alas, it appeared that I was doomed. But then again, with only three days of time, it wasn’t like I had time to visit every gallery in the city anyway. So, I did my homework, located the galleries that seemed to have reputations and set out to explore. And two I visited proved me with a look at world-class art by local Hong Kong artists.

The show write-up on the Grotto gallery website had this to say about its group show, “The Linear Dimension”:

The exhibition concept stems from the different perceptions of line drawings in Chinese and western traditions. While the Chinese artist viewed it as an independent art form (because of its association with calligraphy), western artists perceived them as sketch or studies (because of their concerns with colors and shapes). This difference in perception became less obvious in the 20th century when the two influences, and two cultures, became more integrated, resulting in lines and forms having attained equal status.

This is something that appeals to me. While I hadn’t considered the “sketching” side of the Western argument, I’ve long been fascinated by the linear leanings of traditional Japanese art, more specifically, zen Buddhist sumi-e, which is itself directly descended from Chinese work. The Grotto show featured work ranging from the literally line-drawn to more conceptual interpretations of a “linear” idea. But the one artist that left me with the most lasting impression was most definitely Wilson Shieh.

Entering the the gallery’s main room, visitors are immediately brought face to face with a wall of bald, almost androgynous figures in a variety of sexual positions. It was like stumbling upon a sex manual drawn in a Buddhist monastery. Shieh’s work has the flavour of ancient Chinese drawing, and if often done on silk as well as paper. His subjects range from somewhat regular portraits of nameless people, to images of Hong Kong, and satiric colonial jibes. In one series, he painted iconic Hong Kong buildings with gigantic people trapped inside them. He then took this in a different direction with his later “Ladyland” series, in which the buildings ceased to be cages and instead became dresses — the people now defining the city. Yet there is an interesting ambiguity — are the people the institutions that they represent, or the other way around? Are they portraits of a city, a people, or an economy?

In other works, Shieh paints women whose clothing seems to hide children or men in its patterns or underneath dresses, almost invisible. In Mother, a pregnant woman turns out to be holding a child that is almost camouflaged against her clothes. She is at once pregnant and not pregnant, a mother and a mother-to-be.

Shieh’s human figures are already effortlessly androgynous. But in the images at the “Linear” show, Shieh’s linear drawings seem to be more about blurring lines, especially those of gender. Perhaps the most telling of these works is Snails. In this painting, a kissing couple have similar non-gendered haircuts and are dressed almost identically. Is one shorter than the other, or is it simply the way they are standing? Are both women? Both men? It is impossible to be sure. On their backs, they wear backpacks that have transformed into snail shells: the perfect image of genderless love.

Platycerus Virescens - Angela Su

And in Spring Picture, the set of eight sex positions arranged at the entrance of the show, the genders can be worked out, but only with a more than casual glance. The figures are rendered in profile, without expression, personality or passion. We are left only with a strange air: an ascetic sexuality, a calm passion. Clichés and gender roles drop away, and the images seem to be those of sex as a road to enlightenment.

If the rest of Shieh’s work were like this, one would worry he was taking himself far too seriously, trying to write a kind of modern day Kamasutra. But the rest of his work reveals wit and satire, a leaning toward the surreal, and above all, an eye for line and pattern that make him an artist to watch.

Other artists included in the show were Halley Cheng, Caroline Chiu, Kwok Ying, Lam Tung-pang, Bovey Lee, Joey Leung, Castaly Leung, Wai Pong-yu, Wong Chung-yu and the disturbingly wonderful drawings of Angela Su, who deserves her own entry on some other occasion.