Weekender movie man Jim Bailey on how the Japanese have been going star crazy since the ‘50s

ALTHOUGH IT was past midnight when he disembarked at Haneda International Airport, the actor undoubtedly best known for his memorable portrayal of Jess Harper was met by 2,000 cheering fans. The late hour likely didn’t matter to the enthusiasts, for it wasn’t every day that Tokyo played host to none other than Robert Fuller.

Jess Who? Robert Say What?

Fuller was the second-billed lead on Laramie, a Western series that never broke into the Nielsen top 30 during its four seasons on NBC (1959–63).

When shown on Japan’s NET, however, the program acquired a devoted following. And on Apr. 7, 1961, the man who played Jess Harper better than he’d ever been played before became the latest overseas star to experience the all-embracing enthusiasm that awaits gaijin actors and actresses who visit these shores.

That enthusiasm has engulfed visiting performers big and barely remembered, from silent screen A-listers to cathode ray tube also-rans, whether here for business or tourism. Fans have outwitted security guards, defied the local police and even had to be restrained by foreign troops.

Following a visit to Japan in December 1929, Douglas Fairbanks and wife Mary Pickford required five days “to recover from the strain of hospitality” they experienced, as the Japan Times put it. When the two stepped down from their train at Tokyo Station, reported the Dec. 21, 1929, edition of the aforementioned newspaper, “five thousand ordinarilly (sic) sensible people completely lost their sense of propriety … and broke through police cordons, swept aside the officers of the law in a pandemonium, and broke into a mob.”

One of Fairbanks and Pickford’s partners in United Artists received no less hearty a greeting when he visited three years later. Following a tour through England and France that saw the constabulary regularly called out to restore order, Charlie Chaplin and his brother Sydney arrived in Tokyo in May 1932. Here, they were treated “to crowds and a welcome as spectacular as they were accustomed to encounter in Europe,” according to the comedian’s biographer, David Robinson.

As is demonstrated by Fuller’s promotional jaunt, in Japan, even actors and actresses outside fame’s highest tier have managed to excite the masses. Their days as top-liners long behind them, Joseph Cotten and wife Patricia Medina were contracted to appear in a 1969 sci-fi feature directed by Ishiro Honda, director of the original Godzilla feature. Stepping off the plane, the Cottens were greeted, as Medina described it in her autobiography, “by 5,000 camera bulbs” and a “permanent wall of photographers.”

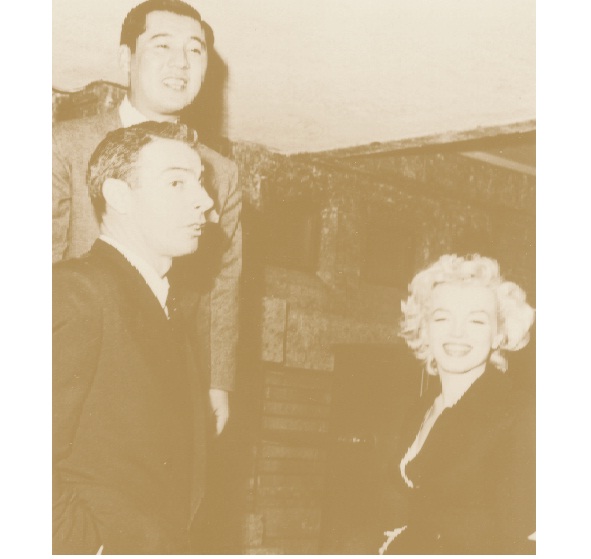

But perhaps the most memorable display of enthusiasm to take place at Haneda occurred in 1954. Newlyweds Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio leave their Pan American Stratoclipper through the rear baggage hatch in order to avoid getting mauled by some 5,000 fans. As Richard Ben Cramer relates in Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life, the fans “blew past the cops, stormed the tarmac” and necessitated the calling in of U.S. Air Force MPs to help restore order. “‘If she had tried to go through that mob,” said a Japanese police official of Mrs. Yankee Clipper, “they would probably have torn all her clothes off.’”

Hoping to avoid any similar scenes on the way from the airport to the Imperial Hotel, DiMaggio told his driver to bypass a predetermined route through the Ginza, where hundreds of thousands had lined up on a cold February day, eager for a glimpse. Cheated, thousands headed for the Imperial. Undeterred by the presence of 200 policemen on guard duty, Joe and Marilyn’s enthusiasts first laid siege to the hotel’s revolving doors, plate glass windows and koi ponds. They then set up a periodically keening vigil that quieted only when Monroe appeared on a balcony to wave and blow kisses.

Inside the hotel, at a televised press conference to which she arrived two hours late, the lust-crazed pushiness continued. One Japanese newsman asked: “We are told you do not wear anything under your dress. Is that true?” Curiously, in his otherwise thorough and entertaining retelling of DiMaggio and Monroe’s Far East honeymoon, Cramer neglects to mention the one Q&A that virtually every vernacular Japanese account, contemporaneous and otherwise, cites as perhaps the most memorable verbal highlight of the celebrity couple’s entire stay.

Asked at the conference what she wore in bed, Monroe replied, “Chanel No. 5.” An excellent rejoinder in English, in which language both clothes and perfume can be “worn,” but slightly less effective in Japanese, which uses different verbs for the two actions. Monroe’s translator, with an intuitive understanding of what sounded most evocative to Japanese ears, refashioned the actress’s response as follows: “Watkushi no negurije wa shaneru go-ban” (My negligee is Chanel. No. 5).

“In a single night,” according to a history of the first 40 years of Japanese television compiled by Terebi Gaido (TV Guide) magazine, “the men of Japan were bewitched.” Given the familiar effects of curvaceous blondes on male minds, it is somehow appropriate that “bewitched” is written with the ideograms for “brain” and “kill.”

But even by the frenzied, brain-killing standard set during the brief run of the DiMaggio–Monroe circus extravaganza, the reaction of fans and media to Sean Connery six weeks location shooting for You Only Live Twice in 1966 was decidedly over-the-big-top.

Although it may strain the credulity of cinemagoers of today’s whippersnapper vintage, the Bond series was the Star Wars series of its day, each installment eagerly awaited by a coterie of never-been-kissed cineastes.

The most successful imported films in Japan for three years in a row, in 1965, 1966 and 1967, were Bond adventures — respectively, Goldfinger, Thunderball and You Only Live Twice. Indeed, by the time Connery strolled into a press conference at a Tokyo hotel in the summer of ‘66, Thunderball had already become the first foreign film ever to earn over ¥1 billion at the Japanese box office.

Having been mobbed in Bangkok and Manila en route to Tokyo, Connery met the press in an understandable state of bleary-eyed exhaustion. His toupee nowhere in sight, the actor was clad in shower sandals, baggy trousers and a blue shirt opened to his chest. A reporter who asked why “James Bond” had dressed in this manner was politely told, according to Stephen Jay Rubin in The Complete James Bond Movie Encyclopedia, “I’m not James Bond. I’m Sean Connery and I like to dress comfortably, except for formal occasions.” Author Bob McCabe, in Sean Connery: A Biography, maintains the actor offered a more curt response: “I’m here for your bloody convenience and I can dress any way I damn well want.”

Whether Connery was conciliatory or combative, there’s little doubt that the actor’s uncovered-head-to-bare-toe version of casual Friday had served to alienate Japanese reporters.

Perhaps even more so than their counterparts elsewhere, the main job of journalists in Japan is to satisfy the preconceptions of their readers. Connery, as a publicity campaign tag line stressed, was James Bond. Further, James Bond was on Her Majesty’s Secret Service, and Her Majesty, to employ a formulaic description known to virtually all Japanese, reigned over what was, is and always will be “shinshi no kuni” — a country of gentlemen, otherwise known as England. Connery not only didn’t look like a gentleman; as reporters were soon to discover, he didn’t talk like a gentleman, either.

Celebrity press conferences, especially those for first-time visitors to Japan, are fairly predictable affairs. To be sure, there’s always the possibility of a left-field query — for example when the members of the Go-Go’s, the all-female 1980s rock quintet, were asked if being constantly in each other’s company while on the road had resulted in their monthly periods becoming synchronized. But most conferences are largely surprise-free: male celebrities, for example, can almost invariably expect to be asked their first impression of Japan and what they think of Japanese women.

In each instance, the best answer is the one which satisfies preconceived notions of foreigners’ attitudes towards Japan. The wise celebrity will declare that his first impression of Japan is favorable and that he thinks Japanese women quite possibly the most attractive on the planet. (Unless the celebrity is rock star Alice Cooper, who answered that he couldn’t offer an informed opinion about Japanese women since he hadn’t “f****d any of them yet”).

Asked his honest opinion about distaff Japanese, Connery stupidly gave it: “Japanese women are just not sexy. This is even more so when they hide their figures by wearing those roomy kimonos.” If the self-descriptively “secretive” actor had hoped that such an undiplomatic remark would render him a pariah, causing press and public alike to scatter at his approach, he was sadly mistaken.

After being constantly followed by photographers, even into the “ruddy toilet,” complained the exasperated actor, Connery was assigned 12 bodyguards who themselves began snapping photos of their famous charge.

Playing Bond, Connery was to have been shot for the film with a hidden camera as he strolled along the Ginza. Instead, as director Lewis Gilbert put it, the actor was “pounced upon by a million fans.” Connery and wife Diane Cilento could not even tour Tokyo in the dead of night due to the crush of paparazzi.

Even before shooting began on this fan- and photographer-plagued feature, Connery had already announced that it was to be his last go-round as Bond.

His month and a half of struggles from Tokyo to the southern island of Kyushu did not cause him to regret his decision in the slightest. Had anyone bothered to translate the Japanese title of You Only Live Twice to him, he might have managed a rueful chuckle — 007 wa Nido Shinu, or 007 Dies Twice.

No less than other visiting actors before and after him, the actor who was Bond had learned an important lesson about dying. Perishing two times in a row is not an uncommon fate in a country where the photographers can’t stop shooting you and the fans won’t stop loving you to death.