by Kit Nagamura

It’s hot outside, but if you choose to brave the rays and head to a park, why not tote along a traditional Japanese toy or two to take your mind off the heat?

One toy touted to help youngsters learn balance — something useful when the mercury soars — is the takeuma. Originally fashioned from two long stalks of bamboo, these are the Japanese rural version of stilts. The first takeuma, or “bamboo horse” was a leafy affair tethered by rope, with notched, backward-facing “stirrups” a few feet off the ground. Modern mass-produced models are aluminum, and can be found in larger Tokyo toyshops, but if you’re interested in assembling a pair of the originals for yourself, you’ll find clearly illustrated step-by-tall-step instructions at www.tnc.ne.jp/oasobi/oasobi02/42takeuma/.

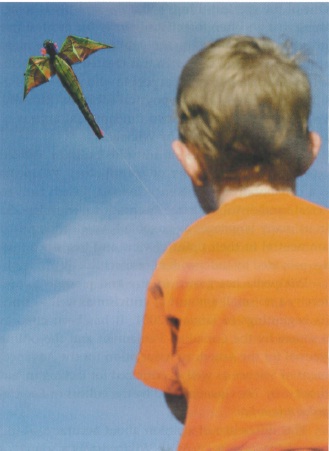

When the wind blows, try taking a tako (the traditional Japanese kite, not the octopus) to the park, but choose carefully. Japanese love extremes, and kites here go from hardly functional miniatures the size of gum wrappers up to sky giants that weigh over 800 kilograms and require the strength of a hundred men to handle. For an overview, visit the Kite Museum (5F, Taimeiken Bldg., 1-12-10 Nihonbashi; Tel. 03-3275-2704). The display spans from antique to modern designs, sure to give a lift to any junior flyer. Pick up an inexpensive kite-making set for the kids or select a hand-painted bamboo beauty for your collection. To launch and land safely, you’ll need a wide, open space. You laugh? Riverbanks are good bets, and some of the larger parks in the city allow airborne antics (try Hika-rigaoka Park on the Oedo Line, or Musashino Central Park, home of the annual Parents and Children Kite Festival.

Suppose your favorite park is densely landscaped with kite-eating trees and rain-filled bogs. Then snag yourself a mushi kago (bug cage) and a mushi ami (bug net), and set out on a nature hunt. Kids can easily spend half the day chasing after cicadas, beetles, butterflies, and even (kid you not) crayfish. It’s wise to have a sit-down session on the kinds of critters to avoid (water beetles bite, suzumebatchi, or hornets, can be deadly, etc.), what to wear (dark clothing attracts hornets, so opt for white) and how to move if a dangerous bug approaches (slowly, without panicking). In order to retain good karma, catch and release is cricket chez moi. However, artistic or scientific kids often enjoy an observation period, which doesn’t have to prove fatal to the insect involved if your mushi kago is well ventilated. Plastic bug prisons are available at ¥100 shops, but the original insect boxes were delicate constructions of bamboo. The history of keeping singing insects extends back more than a thousand years, and even today, a quality mushi kago will run several hundred dollars. As an aside, second floor windows on old traditional homes, such as those you’d find in Kyoto, are known as mushiko-mado, a term derived from the words mushi kago.

To continue on the bug’s life theme, the take tonbo, or bamboo dragonfly, is a deceptively simple toy consisting of a stick bisecting a double-bladed propeller. You hold the stick between your palms and then spin it by flicking your palms in opposite directions. One of two things will happen. Either the toy will hit your hand (in which case, reverse the spinning direction) or it will take off in vertical flight like a miniature helicopter. Little kids love to go catch the dragonfly, and bigger ones might want to try making a take tonbo themselves. Not rocket science, you say? Well, the best instructional site I could find is sponsored by NASA (search “take tonbo” at www.nasaexplores.com).

All toys can be enjoyed by all kids, but hanetsuki (literally, “hit the feathers”) has traditionally been a game for girls. A Japanese form of badminton, hanetsuki is played with hagoita (a decorated wooden bat, or battledore) and delicate hane (shuttlecocks, or birdies). As in badminton, the object is to keep the bundle of feathers in the air, but hanetsuki delivers a satisfying “thwack,” the sound of which used to let people know the New Year’s holiday was in full swing. Nowadays, both hagoita and hane are available, but the simple, painted battledores of yore have given way to heavily decorated hagoita, used more for decorative purposes than play. Since these fancy paddles can reach six feet high, it’s probably a good thing that the current rage is all about collecting them as good luck charms. Built into relief with washi paper, embroidery, and silk cloth, the paddles feature famous kabuki actors, sports heroes, kimono-ed beauties, celebrities, and a few oddities. The hagoita with a smug Hello Kitty in kimono is a birdie’s nightmare. If you want to get into this racket, check out the Hagaoita-Ichi, the annual market held toward the end of December at Sensoji in Asakusa.

Another toy that used to signal the New Year break, but now comes out for a twirl any time of the year, is the koma (spinning top). Believed to have originated in China, early tops in Japan were fashioned from wood, shells, seeds, and (wait for it…) bamboo. The variety of styles is endless. Nari-goma, drilled with little holes, produces a humming sound and the tobi-goma is several tops stacked one inside the other that leap out once in motion. You can still find humble-looking bei-goma — simple string-propelled iron tops — at antique markets. These, and tetsudo-goma, an ordinary wooden top fitted with an iron band around its girth to increase durability, were placed in makeshift arenas to battle for the territory. A few years ago, Beyblade, a top made of interlocking plastic and steel animated by ripcord, revived the battling frenzy; the craze has waned slightly, but the tradition lives on.