I’m not sure I would like to go to North Korea. Not only because I’d be wandering around ogling at the forceful subjugation of millions of innocent civilians like some sadistic voyeur, but also the state-organized tours are dominated by rules, prohibitions, strict government surveillance and a complete lack of freedom.

This may sound rather trivial, but it’s unfortunately relevant, as Japan has taken a leaf out of Kim Jong-un’s book with its new tourism policy. Brooded over by a cadre of fun police – operating under the moniker of “tour guides” – Japan is currently open to organized tours only, reflecting a model effectively unknown outside of the world’s most protected areas and authoritarian states.

What’s most surprising about this is that many have been heralding the move as Japan’s great reopening. But for all the government’s trumpeting about aligning its tourism policies with that of its fellow G7 nations – and at this stage, most of the rest of the world – what we’re seeing is a far cry from the free movement of people being exercised in other democracies.

A Faulty Trial

Japan initiated the opening of its borders to tourists with a “test tourism” period at the end of May, allowing a grand total of 50 travelers from four key inbound markets to embark upon tours organized by a select few travel agencies, all of which work tightly in sync with the government and have very deep pockets.

The pilot program – during which one visitor tested positive for Covid-19 – was designed to collect data to generate “infection prevention” and “emergency response” guidelines for tour operators, accommodations and destination management companies in light of a broader reopening at an unspecified date.

Why two years of domestic tourism hasn’t sufficed to generate said guidelines isn’t entirely clear. People moving freely within a given geographical space is a much better indicator of how viruses are caught, spread and combatted in society than observing the tightly controlled movements of small groups of people.

The decidedly unscientific “test tourism” period also fell short as an experiment because it failed to simulate the actual experience of travel, with all of its spontaneity and freedom of choice. Rather, the test tours were preordained and took place in lesser-visited (and we can therefore extrapolate, less desirable) regions of Japan. Participants were also under surveillance at all times.

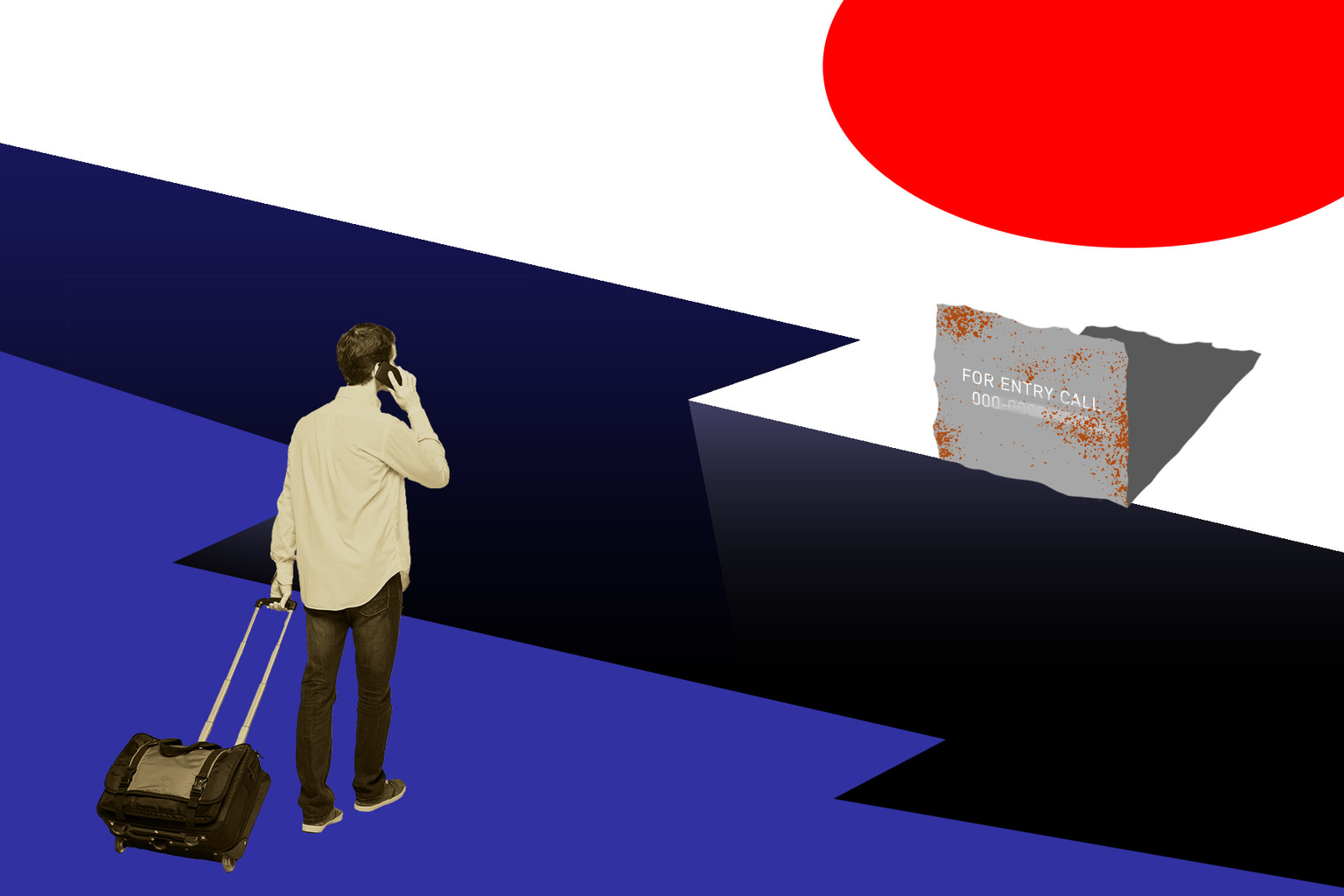

Image by Anna Petek

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

The next phase of reopening, effective June 10, permits travelers from 98 “low risk” countries under an equally strict set of guidelines that makes venturing to Japan sound more like a rule-bound school outing than a trip many holidaymakers have been lusting over for the past two years.

According to the Japan Tourism Agency, visitors are required to join package tours managed and conducted by Japan-registered providers, to be chaperoned for the entirety of the trip by government-approved tour guides, to adhere to Japan’s “infectious disease control measures,” and to take out private medical insurance.

Officials have stated that travelers may be kicked from the tours if they don’t abide by the rules, while tour guides have been ordered to meticulously ensure that they do. The guidelines must be explained to all touring party members, and insofar as I can tell, work under the assumption that grown adults can’t follow simple instructions or use their own intuition.

The edicts stipulate that travel agents “shall conduct training for tour guides to ensure that they fully understand the significance of infection prevention measures” and guides must explain the measures to visitors “using illustrations.”

Nothing to cure jetlag like a seminar with visual aids. And let’s be honest, at this stage in the pandemic who still needs an introductory primer on mask use and the perceived benefits of hand sanitizer?

Furthermore, the initiative exhibits a fundamental misunderstanding about what most tourists want to do in Japan. Tour operators must “prepare itineraries that avoid dense areas,” meaning Japan’s most-visited cities, such as Tokyo, Kyoto, Hiroshima, Osaka – all of which could accurately be described as “dense” – are unlikely to feature in any meaningful way.

And with only 20,000 daily entrants currently allowed into Japan (including residents and work permit holders), most small-to-medium businesses in the travel industry – which account for the vast majority – won’t expect boosts to their bottom lines until fall at the earliest.

The Forces at Play

The government maintains that it needs more time to inoculate the public from Covid-19 and to administer booster shots before fully reopening to tourists. According to Our World in Data, 82 percent of Japan’s population is vaccinated, compared with 80 percent in late November, while over half has received a booster.

If we are to be cynical – and frankly, there’s no reason why we shouldn’t be – it’s clear that there are political elements at play. Prime Minister Kishida’s approval rating recently hit 64 percent; two percentage points shy of the record 66 percent in January. The public, the world’s oldest, has been supportive of overly cautious Covid-19 policies, from ever-masking to draconian border controls. And with a House of Councillors election coming up in July, Kishida is unlikely to upset the apple cart, especially less than one-year into a prime ministerial tenure that threatened to be a poisoned chalice.

The reality, however, is that Japanese citizens are able to freely jet set abroad while their government isn’t extending the same courtesy to other nations. Not only is this morally corrupt, but it also eschews the tangible economic rewards. Japan topped the 2021 Travel and Tourism Development Index, in spite of two years of self-imposed isolation, while the depreciating yen ensures travelers will have increased purchasing power. Both aspects could be vital in facilitating the full return of inbound visitors, who spent over $36 billion in Japan in 2019 alone.

Yet the timeline for a relaxation of all border controls remains as foggy and abstract as it did two years ago. Carefully engineered tours that sound more like a chore than a privilege simply don’t have mass appeal. The question is: How much longer are people willing to wait?