by Graham Davis

So it is the consumer who is thoroughly to blame. They just won’t spend enough. At a time when Japan needs to find all the demand it can, it is just not good enough that Japan’s consumers won’t open the purse strings, get their checkbooks out, throw caution to the winds, and let rip in an orgy of conspicuous consumption.

Tokyo, of course, seems an odd sort of place to make this kind of claim. As a consumer destination it ranks alongside the very best in the world and domestic and international companies satiating seemingly inexhaustible demand for highly priced baubles have made fortunes. But compare the vision from the aircraft as you fly into Narita with what you see when you fly over southern England, maybe into Stansted. On an [admittedly rare] sunny day over the maligned county of Essex, what catch your eye are the expansive houses, gardens, and absurdly, swimming pools. It seems as though southern Britain has decided that it is, in fact, the south of France or California; no house of any standing is complete without its pool and patio. That is what I call conspicuous consumption—something completely irrational—ludicrously inappropriate for the generally miserable climate, but a great point of pride, particularly, I suppose, if you can spot your own from the air.

What catches your eye on the flight into Narita? Small lot houses and farms of course, and the prefecture of Chiba festooned with golf courses. Golf courses: notorious relics of when Japan really knew how to spend—the bubble period. Memberships costing fortunes, the greatest course designers, luxurious clubhouses, manicured greens and fairways—true monuments to an obvious ability to spend. If only consumer Japan could rediscover this latent talent.

But, of course, the subsequent financial problems of golf in Japan tell us very much why consumers are so cautious. There is a lesson here for all those misguided swimming pool owners in the UK, keen to spend their city bonuses and making local builders and estate agents very happy in the process. The city gravy train has now come to a juddering stop and southern England will not be flush with cash for years to come. As in Japan, where million-dollar golf club memberships came crashing down in value once the music stopped, so must the spending.

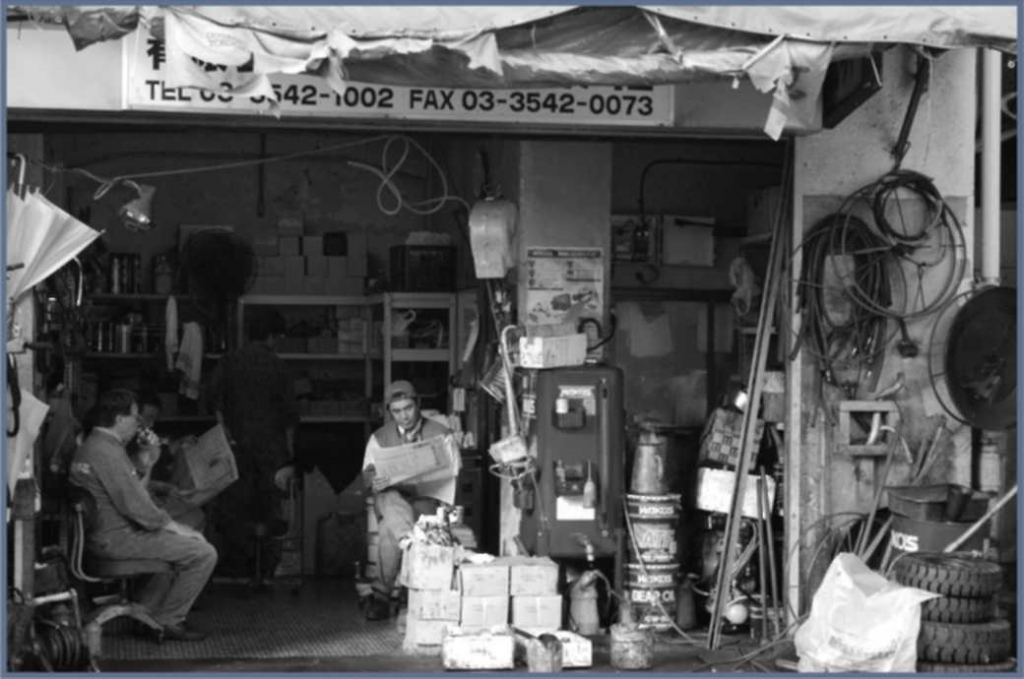

At eye level, too, Japan shows what happens when local economies just don’t work. Take Kita Kyushu. A lot of trucks, a lot of diesel fumes, a lot of drabness, and the sort of urban dereliction that belongs in The Sopranos. In fact, you can almost imagine Tony Soprano operating in this environment, maybe setting up shop with a tire business. It would be an interesting task to count the number of tire establishments, used car lots, truck repair shops, and other vestiges of Japan’s automobile history in this area of Kyushu. This is not to say that there is no other activity—on the contrary—for fans of the steel works or chemical plants, this New Jersey of Japan would be the ideal holiday destination.

For me, cycling through Kyushu in the relentless heat of the summer of 2008, this area, with its pachinko parlors, down-at-heel shopping malls, light engineering, and more tire shops and car repair centres than any major city needs, tells us a lot about why Japan does not create enough wealth domestically to finance swimming pools and extravagant country mansions. When the only new businesses are hairdressers and pet salons that struggle to make ends meet, and old business seems to operate at subsistence level, what chance can there be for wealth creation and vibrant local economies? No city bonuses to be spent here, no nannies to be employed, no local builders, and craftsmen feasting at the trough of whimsical indulgences. Neither money being generated in the local economy, nor money being parachuted in from outside—rather an area, like so many in Japan, which seems like an economy isolated from any chance of success.

“Japan’s consumers won’t… let trip in an

orgy of conspicuous consumption.”

This is not to be critical of Kita Kyushu, where Fukuoka is one of the bright and vibrant hopes of regional Japan, benefiting from prosperous business connections with Korea and Taiwan. Rather it is to lament an economic structure where vast areas of Japan are sustained not through their own efforts but through dependence on wealth redistribution—the largesse of the urban taxpayer. A day after I passed through Kita Kyushu, in true rural Japan, heading for the west coast on the borders of Fukuoka and Kumamoto prefectures, I witnessed roads that were perfect and idyllic scenery in the immaculate farms—rice fields and rivers rather than rubber and reinforced concrete. The roads, of course, are outstanding, with clean, true surfaces and not much traffic. It is a coastal plain on the route 501, long and straight, and a combination of fishing and rice—and let us be honest, huge government handouts for construction and agriculture—which makes this a prosperous area.

“Does Japan need all the tire businesses,

hairdressers, and pet salons competing for our yen?”

So there’s money here, no doubt about it; but unlike the urban areas of Kita Kyushu, hardly anyone around, and. it seemed to me, hardly anywhere to spend all of this wealth. For all the pleasant scenery too, the housing could scarcely be described as opulent—functional at best, and certainly a far cry from the fake mansions de rigueur in the UK until the money-go-round stopped. I even wondered whether it is possible that a lot of houses in Kyushu are not connected to the sewerage system.

Every so often, very often in fact, a truck with a tank on the back with a large hose attached smelling somewhat agricultural would overtake me, poisoning the atmosphere.

Can Japan create demand? It certainly did in the bubble era—but in retrospect, much of that consumption was by corporates for their executives and, so despite the luxury goods boom, not all of the spending by any means was by Japanese consumers. Monumental corporate extravagance is a thing of the past and the legendary frugality of the Japanese family, with its strong savings rate is now more the guiding influence. But when so much business seems to run on a shoe string, the ability to generate high profits, wages and—dirty word these days—bonuses, will always be restricted. Does Japan need all the tire businesses, hairdressers, and pet salons competing for our yen, or are all of these businesses simply a means of subsistence for their owners? Economies need to create wealth and too much subsistence business means an excess supply of things people don’t really want or need and an inability to create wealth, which will create demand.

Of course, an outdoor swimming pool in a frigid island off northwest Europe shows what happens when consumers go a little bit mad; no one should advocate excess demand for unnecessary and extravagant fripperies. If only Japanese consumers could even afford such insanity.

Graham Davis is the Director of The Economist Group, Japan. His wife runs a popular restaurant in Takanawa.