What does it mean to have a truly “rich” lifestyle?

This is the question that a recent panel discussion held by one of Japan’s largest construction firms set out to answer. The Japan Area Home Builders Network (JAHBnet for short), along with the Aqura Home Group, held their 18th annual symposium last week, working under the theme of “Connecting People and Creating a Rich Lifestyle.”

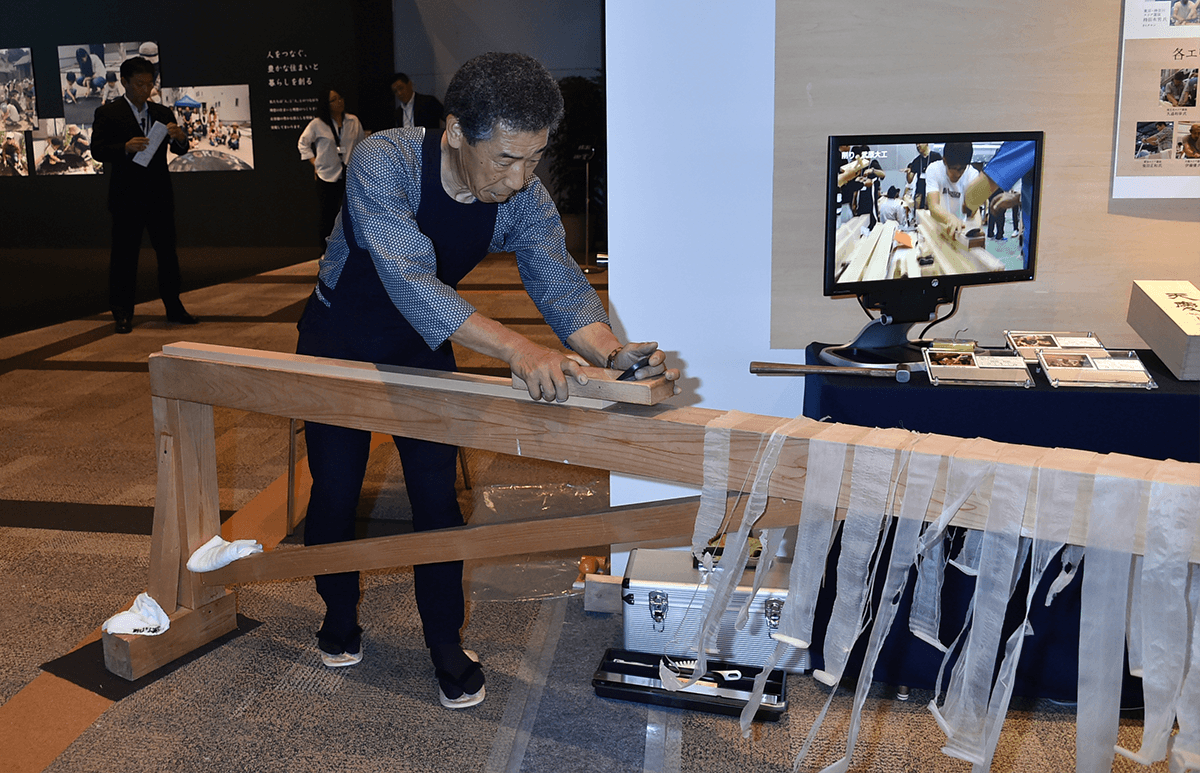

One of Aqura Homes and JAHBnet’s hallmarks is its dedication to the carpenter’s skill; here, an artisan uses a carpenter’s plane to shave off pieces of wood that are as thin as pieces of tissue paper

The keynote speaker, Taro Ashihara, former president of the Japan Institute of Architects, used the example of how the multifamily compound where he grew up served as an example of how a rich lifestyle involves both living close to one’s extended family and being able to make changes to existing structures in order to accommodate the changing needs of an extended family. Highlighting the importance of strong connections within a group as another form of affluence, Ashihara spoke about Bhutan’s concept of Gross National Happiness, and the way of life in small Italian villages. Finally, rejecting the idea that having a lot of possessions leads to happiness, he called for a movement towards building small, smart houses on a global scale.

The panel discussion that followed included Ryotaro Furukawa of Furukawa Design Office; Eriko Horiki, a washi (traditional Japanese paper) artist; and Kenji Igusa, Head of Design at Aqura Home Group. Furukawa, whose firm specializes on uniting architectural and landscape design, focused on the importance of living close to nature as part of a way to have a “wealthy” lifestyle. Horiki spoke about why it was necessary to have passion and enthusiasm as a part of a wealthy lifestyle. Meanwhile, Igusa spoke about how to help clients find design and architectural solutions that fit their needs.

We caught up with Horiki, who is collaborating with Aqura Home Group to provide lighting solutions for their housing designs after the panel discussion to find out more about her pioneering work in a tradition that dates back some 1,500 years.

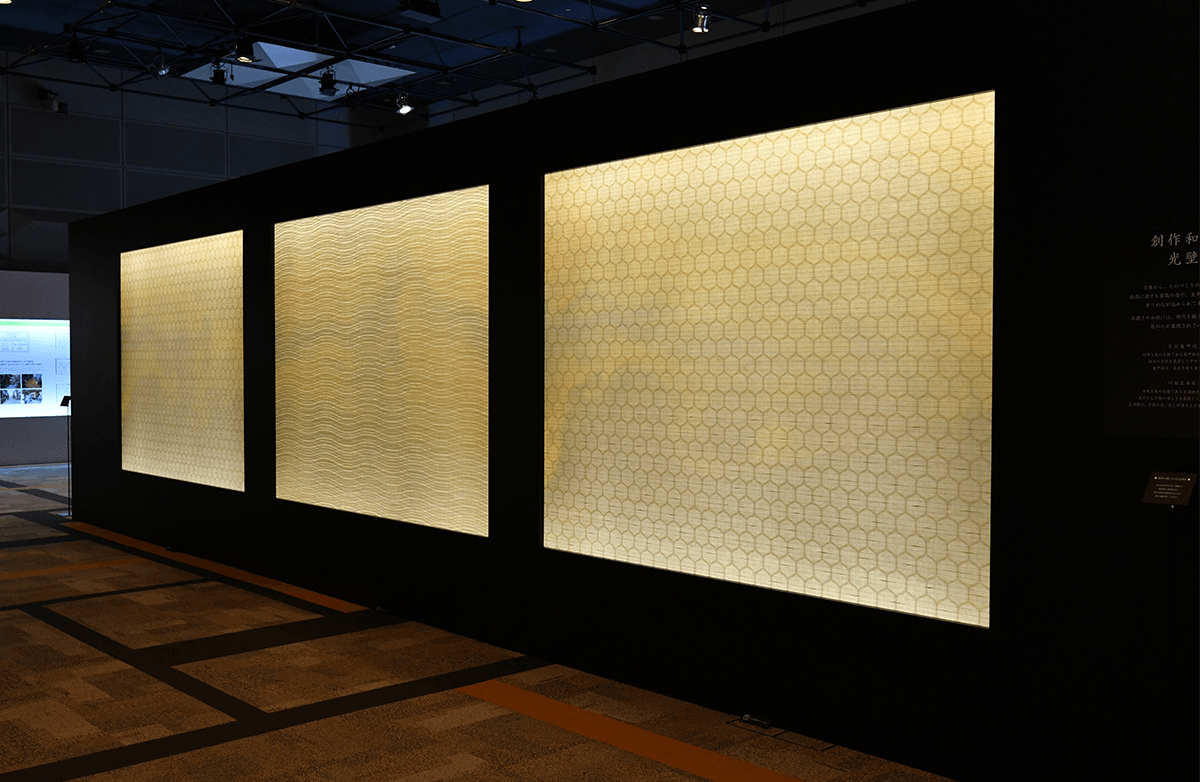

A series of illuminated washi panels created by Horiki; the artist is collaborating with Aqura Homes to bring products made with traditional Japanese paper into homes around the country

As she explained, Horiki did not come from an artisanal background; in fact, even though she has been working with washi for three decades, her first career was in banking. She never saw that lack of experience as a bad thing; on the contrary, it helped her push the boundary of what is possible to find new ways of working with the material. “Often when I would ask traditional artisans to make something new, they would say that something might not be possible. So, many times I would try to do it myself. Sometimes I would find that I couldn’t do what I wanted, but many other times, I could.”

This spirit of experimentation has brought Horiki to come up with a wide variety of innovations: creating types of washi that are durable, stain-proof, and flame resistant; making pieces of washi that can be attached to surfaces without glue, and making washi sheets that are as large as 10 meters wide are just a few examples. Horiki’s factory is based in Echizen, a region that is close to Fukui Prefecture, and a place where washi has been made for 1,500 years. All of the work is done by a team of 10 people: five designers and five artisans. All of the wood used to make the washi is harvested from small kozo bushes, making a minimal impact on the environment. She sees her work as two-fold: carrying old traditions into the future, and developing new traditions based on her factory’s innovations.

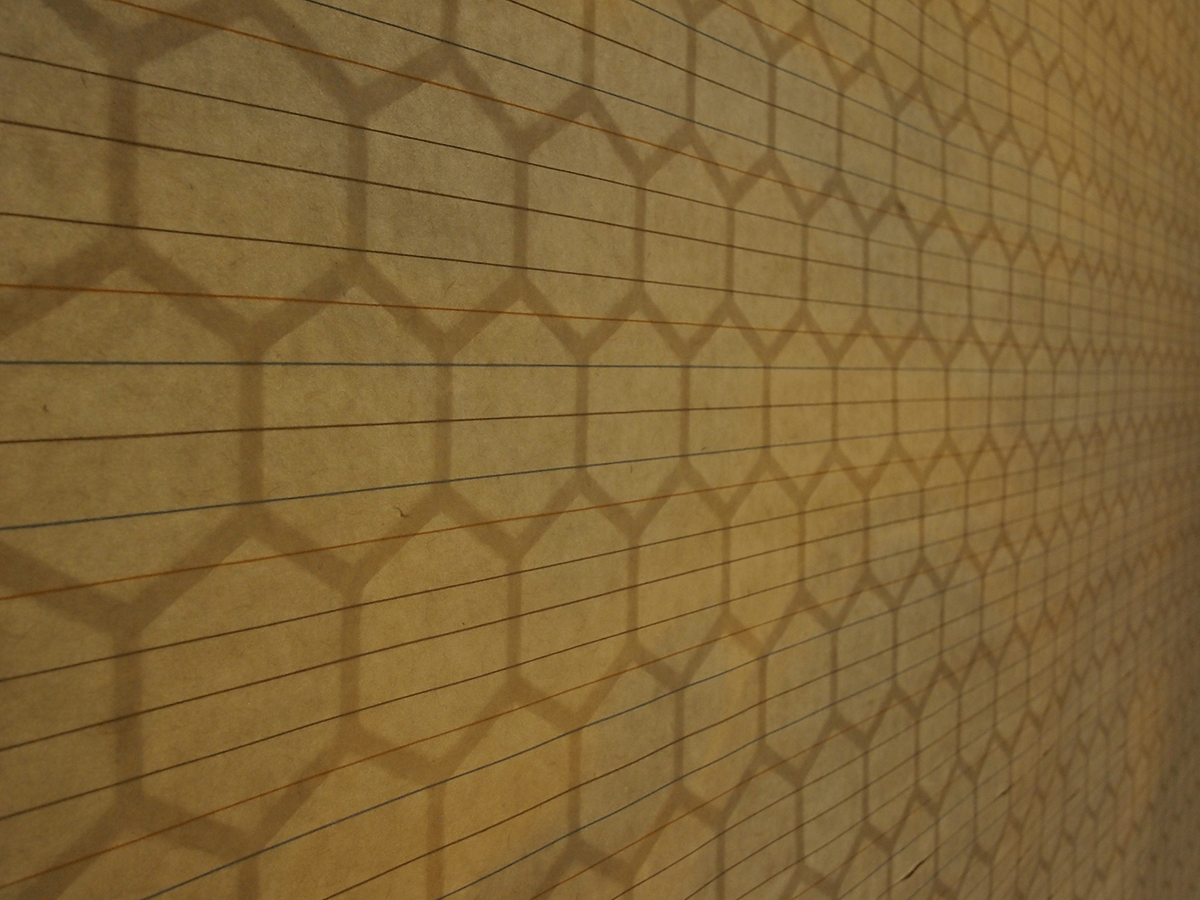

One of the traditional concepts that Horiki continues to develop through her work is utsuroi, a Japanese term that applies to the subtle changes of light and shadow that can be seen through the paper. Many of her creations consist of four to seven sheets of washi stacked on top of each other, and the contrasting and overlapping patterns intensify this effect many times over.

Over the years, Horiki has collaborated with lighting companies such as Baccarat and done installations in public buildings around Japan. Now she sees her partnership with Aqura Home Group as an opportunity to bring another kind of richness to customers’ daily lives: “I believe that culture comes out of what people do day to day, and there’s nothing that would make me happier than creating a culture of functional beauty.”