How Beate-san gave Japanese women their basic rights

by Henry Scott Stokes

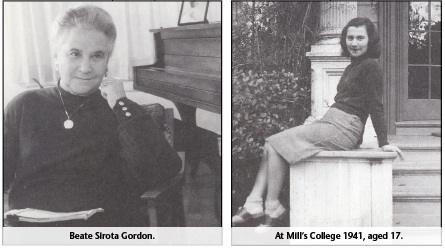

I have been asked to introduce that formidable lady Beate Sirota Gordon. Well, I am not sure that she needs an introduction as she is so well known as a struggler for women’s rights. Beate—now 83 years old, and living in New York City —stands second to none among westerners in Japanese history as a feminist of note. While only 22, when working for the US Occupation authorities in Tokyo in 1946, she got an article inserted into Japan’s newly drafted 1947 Constitution that gave women here their rights for the first time. Some achievement! Until then, amazingly, they were all but legally nonexistent; they had no right of inheritance, nor of property nor divorce! Women here in Japan have Beate-san to thank for Article 24, which established their basic rights. Without Beate, ladies would have been permanently in the proverbial doghouse.

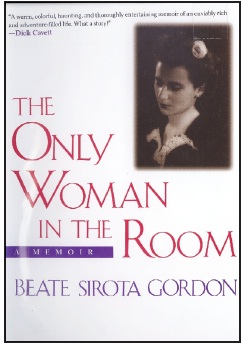

I am happy to re-tell Beate’s story—with a helping hand from my friend James Brooke, then of The New York Times, whose article of May 28, 2005, headed “Fighting to Protect Her Gift to Japan”, recounts a meeting with Beate-san. By way of introduction, Jim tells how Beate- san, an only child, came to Japan with her Ukrainian Jewish émigré parents at age five in 1929, traveling from Vladivostok by ship. Her pianist father, according to the article, secured employment in Japan, where he taught and gave concerts. Fast forward to the late 1930s. Beate, a bright student, moved to Mills College in Oakland, California and she was still there in the US when the Pacific War broke out, cutting her off from her parents. Beate had to fend for herself. She used her Japanese to make US Government wartime radio broadcasts that were beamed to Japan. She also worked as a researcher on Japan for Time magazine. In January 1945, she obtained American nationality.

Beate, she says, believes that

conservatives who want to turn the

clock back to more traditional rules

for women will not succeed: “After

60 years, it would be very hard to

amend it now, it is so much part of

Japan’s culture (now)”.

As soon as war ended in August 1945, Beate hastened to Japan, to find her parents—they had been kept in detention in the mountain village of Karuizawa. They were OK, she saw, but her father was terribly thin, and they were short of food and fuel and all basic supplies; like the vast majority of Japanese, for that matter. Beate raced back to Tokyo and found a job with the Occupation authorities—an all-American team headed by a Lt. Col. Charles L. Kades. That office, as it happened, was suddenly and unexpectedly charged with a huge responsibility. General MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP), had grown impatient of Japanese attempts to write a new and democratic constitution, to replace the Meiji Constitution of 1889—deemed to be a relic of feudalism. The general, who served as a Shogun of his times, was armed with powers plenipotentiary. He issued a new order. His boys—and one girl—must do the job instead. I quote from Jim Brooke’s story in the NYT, itself quoting Beate: “The general’s lawyer, Brig. Gen. Courtney Whitney ‘called us in and said, “Ladies and Gentlemen, you are now a constitutional assembly and you will now write a new draft of the Japanese Constitution, and it has to be done in seven days,”’ she recalled.” Beate said: “We were stunned”.

So, they got to work, with Kades as leader. Beate was the office gofer. Off she went on a bicycle—there were few non-military conveyances in the city—pedaling furiously around shattered Tokyo, looking for public libraries (or any library) that held tomes on constitutional law that she might borrow for Kades. His team was starting from scratch. No one had written a constitution in America since 1776. Information

was lacking and expertise was in short supply. Col. Kades wanted to check and see what others had done in his place. Beate found some useful reference works, and pedaled back to the office. This is my image of Beate-san at that time—a 22-year-old-girl hastening through the streets on her bike. Back in the office, there were only 25 people—24 men and one woman—on the team. Kades spread the work around. Brooke quotes from Beate’s memoir The Only Woman in the Room. He recounts how “in the grueling week of debates, almost all of the clauses that emerged from (Beate’s) Underwood typewriter ended up in the trash basket”. At one point, Beate recalled “Colonel Kades said (to her), ‘My God, you have given Japanese women more rights than in the American Constitution’”. To which she responded, “Colonel Kades, that’s not very difficult to do, because women are not (found) in the American Constitution.’”

Beate pressed on with her Article 24 draft. It stated in part:

“Marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes and it shall be maintained through mutual cooperation with the equal rights of husband and wife as a basis.”

Beate, according to Brooke, was wearing a pink printed silk scarf, when they met in 2005. The scarf had been printed with Article 24 in the six languages that she speaks, namely English, Japanese, Russian, German, Spanish and French. She whipped the scarf off and read to Jim:

“With regard to choice of spouse, property rights, inheritance, choice of domicile, divorce and other matters pertaining to marriage and the family, laws shall be enacted from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes.”

Beate, she says, believes that conservatives who want to turn the clock back to more traditional rules for women will not succeed: “After 60 years, it would be very hard to amend it now, it is so much part of Japan’s culture (now)”.

I agree. In fact, it would be hard to amend any part of the constitution at this point. To amend requires a two-thirds majority of elected members of both houses of Parliament, the Upper House and the Lower House. Unless both the ruling party (the Liberal Democratic Party today), and the opposition combine forces, it is difficult, if not impossible, to assemble a two-thirds majority. The constitution has held firm for more than 60 years without any serious challenge, and it looks like continuing on its way, whatever criticisms are made.

Criticisms? Yes, some Japanese have told me that the Charter is written in poor Japanese, and is an insult to the nation. Others say that it is marred by imported concepts. Beate has an answer to the second charge. She says that “many of Japan’s core cultural attributes were borrowed from overseas— Buddhism, ceramics, ancient court music and the [Chinese] character writing system”. The Constitution has been implanted, as securely as Buddhism over l,000 years ago! Well, almost. Japan’s just -retired premier, Shinzo Abe, started off his year in office in 2006, by saying that he would reform the constitution. To do so might take him six years, he added. Still, he would press on, he said. But his hopes were of no avail, and surely unrealistic. The LDP has wanted to reform the constitution ever since the party was created in the mid-1950s. The party was in fact formed by merger in 1955 precisely with constitutional revision in mind. And yet revision proved to be impractical. The mathematics does not favor revision!

Brooke gives Beate the lion’s share of the credit for getting Article 24 into the charter. The test came “when the draft was submitted to a group of Japanese ministers and politicians for approval (very late one night, when people were exhausted)”. Beate-san recorded the indignant reaction of the dignitaries to the draft: “Immediately they said, ‘this doesn’t fit our culture, doesn’t fit our history; it doesn’t fit our way of life”. This confrontation was taking place at 2am and at the end of 14 hours of debates on other questions. The clock was ticking on and, records Brooke; “the young American woman had won the gratitude of the Japanese leaders for backing them [in her fluent Japanese] in previous disagreements with the Americans.” The dignitaries piped down. After all it was 2am.

Colonel Kades, the chair, then asked a question: “Miss Sirota has her heart set on the women’s rights clause, so why don’t we pass it?”

That was on March 4, 1946. That article 24 is in there in the supreme law of the land, as you can check by Googling “Japan, Constitution”. Sixty-one years later, Beate is still alive and kicking. Just last Friday (that was on October 26) she was touring in Chicago, giving an address to the Japan America Society in that city on her book The Only Woman in the Room.

But here’s perhaps the oddest part of her whole story. For nearly half a century—partly out of a feeling for Japanese sensitivities—the members of the group that drafted the Constitution under Col. Kades, most of whom are no longer with us, kept silent on their project. It is only since 1995 that the truth came out, and Beate published her work. Their silence, if finally broken, seems to me a token of the fact of how dedicated were the Americans who did this job. They cared nothing for publicity. If Beate speaks out now, as I understand it, she does so in order to counter the remarks of those in Japan, who are not lacking in resources, who would like finally to undo what she wrought.