On a bare stage of hinoki beneath an overhanging roof, noh dramas featuring gods, monsters and ghosts, as well as the troubles of everyday people, have been unfolding, largely unchanged, since the 14th century. Conjured without the need for eye-deceiving scenery, these visions of a Japanese dream-world are revealed to the audience in front of a simply painted pine tree; a solitary evergreen backdrop that gives focus to the story, regardless of its setting in time or place.

In the 20th century, elements of this minimal and eerie art form found their way into the work of a small-but-important coterie of western artists. Searching for new ways of describing a world of sudden and sometimes terrifying change, poets and dramatists such as Ezra Pound, W. B. Yeats and Bertolt Brecht found inspiration in the formal stillness of noh. Echoes of its sometimes-disorienting music can also be heard in the work of several 20th century western composers.

Startling Modernity

Accompanied by drums and a flute of smoked or burned bamboo, noh’s narrative exposition is achieved by the chant-singing of the actors and a chorus. Shifting rhythms, notionally structured around an eight-beat pattern, lose or replace beats in an organic fashion, while the viewpoint of the actors can switch between characters in a perspective-shattering cubist style. These complex elements, rooted in antiquity, can seem startlingly modern, and have clear parallels in the work of contemporary composers such as Philip Glass and Steve Reich.

Direct influence, however, can be found in the work of Harry Partch and Olivier Messiaen. Delusion of the Fury, Partch’s masterpiece of microtonal musical theater, was based in part on the noh drama Atsumori, while Messiaen’s Seven Haiku: Japanese Sketches, was inspired by the composer’s discovery and embrace of noh, as well as other traditional music, during his 1962 Japanese honeymoon.

Karlheinz Stockhausen was profoundly affected by his trip to Japan in 1966, when, under commission from NHK, he created his “music of the whole world,” Telemusik. Incorporating elements of global and Japanese music, the resulting electronic audio-collage also pays homage to noh. Stockhausen was so taken with the art-form, that during his joyfully jet-lagged and productive stay in Tokyo, he attended 30 performances.

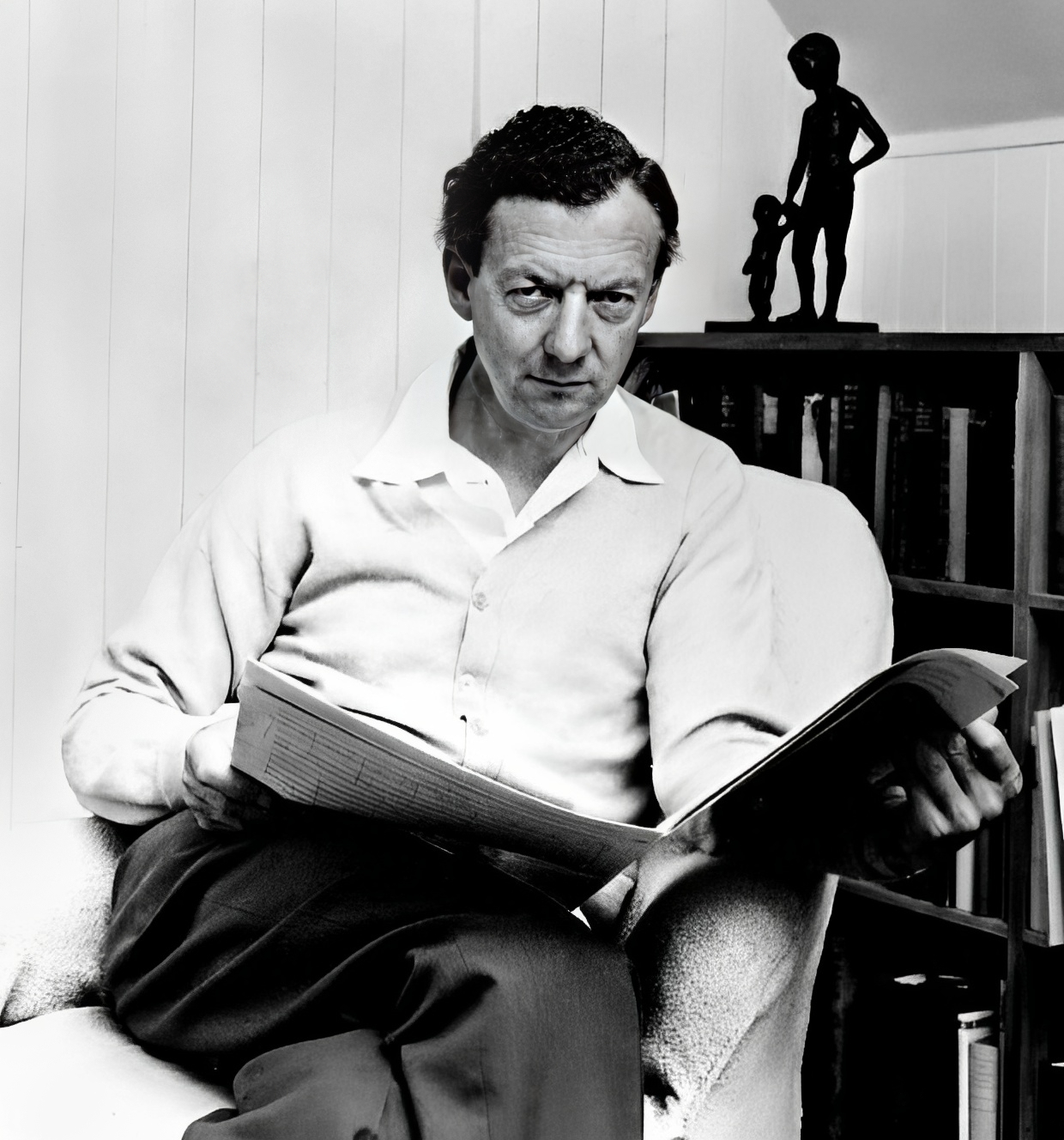

It was a similarly inspirational trip to Japan, and an encounter with the transcendent artistry of noh, that led to the creation of Benjamin Britten’s moving cross-cultural modern opera Curlew River.

Benjamin Britten by Hans Wild

Sumidagawa and Curlew River

Kanze Motomasa’s 15th century tragic noh masterpiece, Sumidagawa, is a play that, with stark and mystical simplicity, tells the final chapter of a mother’s search for her missing son. Frantic in her concern, the mother travels on foot from Kyoto to Musashi province, the site of current day Tokyo, where she finds herself by the banks of the titular river. Guided by the boatman with whom she makes a fateful ferry crossing, she attends a somber moonlit ceremony in a secluded place, where at last her agony of uncertainty is met with an answer. Neither the mother’s story nor the play has a happy ending.

The deeply human universality of the themes of Sumidagawa meant that half a millennium after Japanese audiences were first moved by the story and its tragic conclusion, Britten was able to relocate the narrative, with a minimum of tweaking, to the fenlands of eastern England. Softening the bleak conclusion somewhat, with the light of heavenly salvation, Britten presented his modern opera as a Christian parable and named it Curlew River.

Loss and Resolution

Britten’s attendance in Tokyo at the two performances of Sumidagawa, during which he found inspiration, is itself a story of loss and resolution. In 1939 Britten had been commissioned by the Japanese government to write an orchestral work commemorating the 2,600th anniversary of the founding of Japan. This celebratory invitation had been extended to notable European and Japanese composers, including Hisato Ohzawa, Jacques Ibert and Richard Strauss, whose Japanese Festival Music was written under the instructions of Joseph Goebbels.

The then-imperialistic nation of Japan, and Britten, a lifelong pacifist, were not destined to see eye-to-eye. The composer was reluctant to produce music that could be regarded as jingoistic. A series of ill-tempered miscommunications meant that time to complete the commission ran short. Britten’s eventual submission, Sinfonia da Requiem, a stirringly dark piece with a clear anti-war message, was rejected out of hand by an unimpressed organizing committee, whose letter of rejection stated, “we are afraid that the composer must have greatly misunderstood our desire.”

Nogaku zue by Kogyo Tsukioka / Daikokuya Matsuki Heikichi

A Cultural Coming-Together

In 1956, Britten and a peaceful post-war Japan would be reconciled in a mutually fruitful meeting of artistic minds. Britten and his partner, the tenor Peter Pears, visited and performed at two concerts in Japan at the invitation of NHK. At the second of these events, Britten would conduct the NHK Symphony Orchestra in a performance of his Sinfonia da Requiem, a piece of music that had at last been welcomed in its intended home, a country that now enthusiastically embraced its message of peace.

During Britten’s stay, he would be greatly impressed by many of the traditional performing arts of Japan, but it was noh, specifically a production of Sumidagawa, that made the deepest and most profound impression on him. Attending another just days after the first, he later stated it was “among the greatest theatrical experiences of my life.”

Eight years after this cultural highlight, in his native country of England, the composer’s completed Curlew River had its debut. The restless and unstoppable flow of artistic inspiration having carried Motomasa’s tragic noh tale across far-flung centuries and continents, Britten’s heartfelt Christian variation on Sumidagawa opened at the Church of St. Bartholomew in Orford, a tiny Suffolk village on the banks of the River Ore.