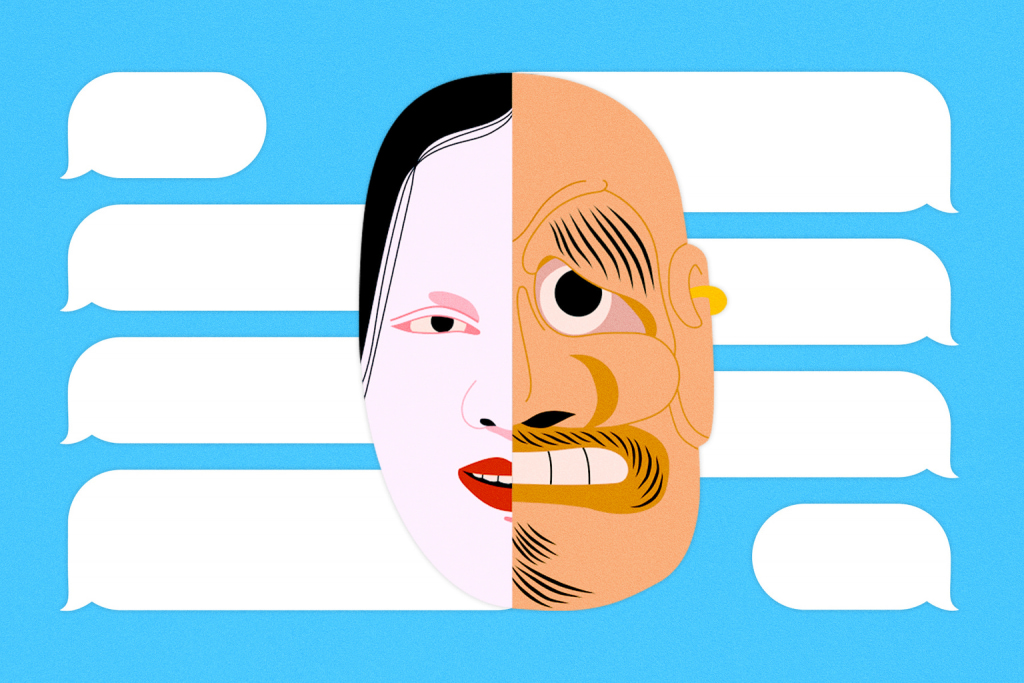

It’s pretty common for older men to pretend to be young girls online, but in Japan you can also find the exact opposite. It’s called ojisan gokko (lit. “old guy make-believe”), a sort of game where young women text each other or post to social media in a way to make themselves sound like lecherous, male creeps. Upon finding out about this, we immediately had lots of questions.

To help answer some of them, we sat down with Dr. Wes Robertson, a sociolinguist of Japanese at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, and one of the few experts studying online Old Guy Make-Believe.

1. What is ojisan gokko?

Ojisan gokko, also known as ojisan koubun (“old guy syntax”), is a practice where young Japanese people (mainly women) message each other pretending to be ojisan. Importantly, though, the term “ojisan” as used here doesn’t refer to its “normal” meaning of a generic male somewhere between 35 and 60 or so. Rather, just like “boomer” in English, “ojisan” refers to both a literal age group and a socially defined identity. For the practitioners of ojisan gokko, the specific ojisan they’re pretending to be is a man who is not just middle-aged, but also lecherous, annoying and lame when they are trying (awkwardly) to seduce young women via text messages.

2. But why…?

Simply because it’s fun and funny. Young Japanese women understandably don’t enjoy being hit on by sketchy older men, so it’s no surprise that they enjoy parodying and mocking a group they’re hostile to. They put a lot of time and work into making their messages “exquisitely uncomfortable,” as one writer I found called it. They also enjoy getting reactions from their friends. By extension, it’s also a source of online clout. Many people post their successful ojisan gokko interactions on Twitter.

3. So, in a way, it’s a kind of power move?

It’s also a form of social resistance. Throughout Japanese history, we have centuries of data and cases showing older men complaining about and policing the language use of younger women. Ojisan gokko flips this power structure on its head. Young women show off their superiority in the online space by mocking older men’s inability to write in a way that is cool, becoming the gatekeepers of language in a manner that inverts the typical “old complaining about young” pattern. In doing so, they also resist and humiliate the ojisan identity itself, turning what is in real life a source of online harassment and potentially even real-life threat into something that can be recognized, mocked and — by extension — potentially resisted or controlled.

4. Can you take us through a typical ojisan gokko conversation?

The basic way to start is some kind of greeting, usually before or after work written it in kanji, often followed by a sun or moon emoji. Then you want to complain about your day at work. After this, you start to get a bit creepy. It’s rare that you just come out and say something vile like “Let’s f***.” Rather, you hint at things in a way that’s lame. Examples I saw in my data are things like, “I don’t think I’ll be able to wake up tomorrow without some racy photos.” While doing this, be sure to call yourself ojisan, written in katakana, rather than use a first-person pronoun.

Finally, after you insinuate something sexual, write nanchatte and then put one or more emoji or kaomoji that show a face sweating or reference sweat. Nanchatte is a really lame way of saying “just kidding,” but it’s also used to hedge commitment like saying “Just kidding… unless, you’re okay with that?” Or, “It’s just a joke, but, let me know if you’re interested, haha.” You can also keep writing back and forth as ojisan, so it looks like two ojisan flirting with each other. Whoever breaks character loses the game.

5. How widespread is this phenomenon?

The peak of popularity was in 2017. There was a survey done with 453 girls between 16 and 18 by a company called TesTee Lab. They found that just over a quarter knew about the practice. A few months later companies like Sony and Tanita made ojisan gokko joke posts on Twitter. I personally started collecting data in 2018 and was able to find around 21 new posts on Twitter a month. Given that this only includes acts of ojisan gokko on Twitter, it’s only a fraction of the actual amount “in the wild.”

Most ojisan gokko is never seen by anyone except the sender and receiver. Ojisan gokko is going strong, but ojisan koubun has completely supplanted [the name]. There’s even an ojisan koubun board game now and it looks like last year ojisan koubun got its own Wikipedia page. So, there’s no question that people are still very much enjoying the practice, but it may have lost a bit of its edge. We’re now at a level of saturation where ojisan are likely even aware of ojisan gokko.

6. What made you want to study ojisan gokko?

My initial interest was just that it was quite funny and that it involved script play (i.e., nonstandard uses of kanji, hiragana, or katakana), so it seemed like an enjoyable research project that aligned directly with my research interests. As I sat down and started working through it, though, I noted that it actually went beyond anything I’d seen before.

7. Your initial findings really took you by surprise, correct?

What I found when I started looking through ojisan gokko is that the authors were using marked versions of hiragana, katakana and kanji all at the same time. But it wasn’t random either. The authors often wrote certain words normally written in hiragana in katakana, for instance, but for others they used kanji. Likewise, some words normally in kanji appeared in katakana, while others appeared in hiragana. I’d never seen a case where an author emphasized the presence of multiple scripts before. So quite early on I got excited, as it went beyond my understanding of what Japanese people actually do.

8. Who first came up with ojisan gokko?

Ojisan gokko is the end of a long line of acts of people in Japan observing how other people write. Initially, young Japanese people started using katakana for Japanese words online for emphasis, fun, or whatever. This then got emphasized by women working in hostess clubs as a way to stand out and attract customers. They would message their clients, often ojisan, using exaggerations of youth writing style.

The ojisan who got these messages then misunderstood them as “normal youth texting” rather than an exaggeration and in attempting to imitate the style, introduced their own writing habits. Young women then observed this new style and exaggerated it as a form of mocking. We’ve seen this somewhat in English too, such as the use of “sweaty” instead of “sweety” to mock older writers. No one says “sweaty”, but the typo is associated with “boomer writing.”

9. So ojisan gokko isn’t how real older men actually text each other?

Ojisan gokko started from some young women, but it’s specifically how creepy older men write to women they are sexually interested in. It’s a parody of a failed recreation of an exaggeration of a “real” writing style. Young women aren’t just pretending to write like old men, they’re writing like old men trying and failing to write like an exaggeration of young women.

10. Is there a female equivalent of this like, say, Obasan Gokko [Old Woman Make-Believe]?

According to the ojisan koubun Wikipedia page, yes. And this Tweet shows it’s actually been covered on TV:

「おじさんLINE」に続き「おばさんLINE」も可視化されてて笑ってます。 pic.twitter.com/X85jPM44tp

— 小悪魔な肺炎 (@play_doll_1982) February 23, 2021

There are also similar things like otaku koubun, where you write like an otaku (geek), so there’s no question that Japanese people are paying attention to and commenting on the online writing habits of many, many groups. As more and more people use online communication, there’s no doubt that we will see even more incredibly detailed parodies.

For more from Dr. Robertson, check out his blog or listen to his podcast about the use of language in the extreme metal scene.