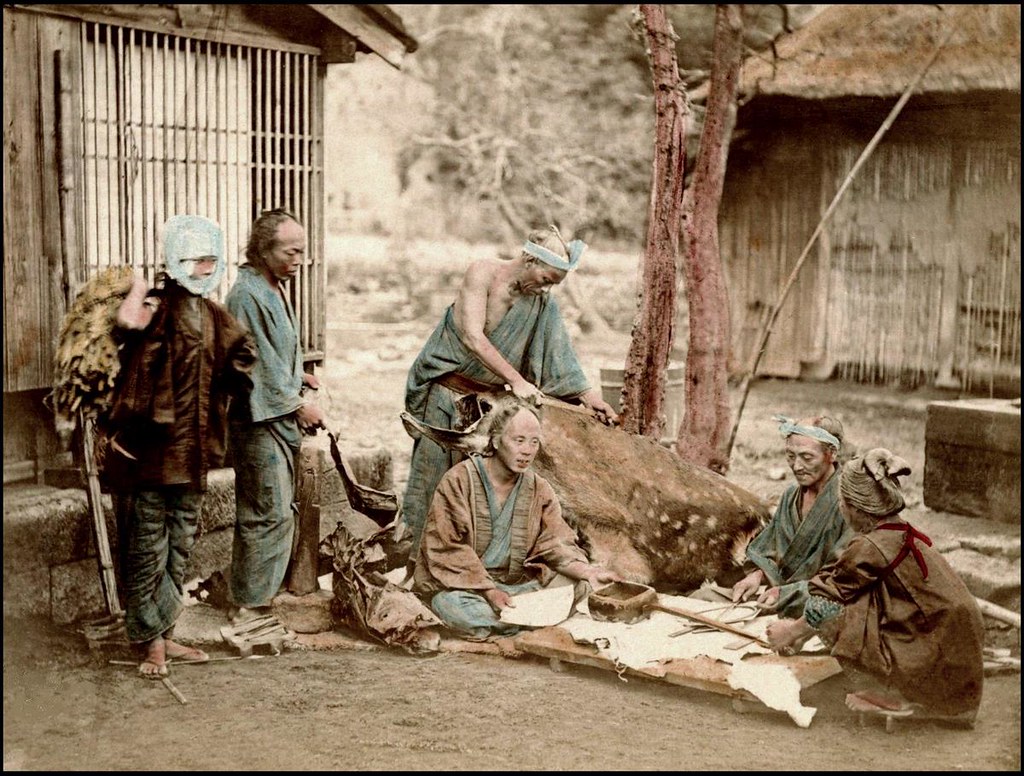

One of Japan’s “untouchable” castes during the Edo Period (1603–1868) were the Eta, who tanned hides and worked with the dead (occupations considered unclean in Buddhism) and whose name literally meant “many sins.” The other group was the “non-human” Hinin made up of beggars, performers, prison guards and other workers.

Collectively, they were known as Hisabetsumin, meaning “discriminated outsiders,” which they felt at every step by being confined to ghettos within the city and generally kept away from Edo society. But they were still expected to contribute to it by taking orders from Eta chieftains, a succession of outcast leaders who ruled over a shadow city within Edo and who all took on the name “Danzaemon.”

Danzaemon’s Kingdom of Skin and Monkeys

A Danzaemon chieftain was responsible for all discriminated against outsiders in Kanto, Izu and parts of other provinces going as far as Mikawa (modern-day Aichi Prefecture). In Kanto alone, that gave them control over nearly 8,000 households during the late 17th century, making the title of Danzaemon a position of great power.

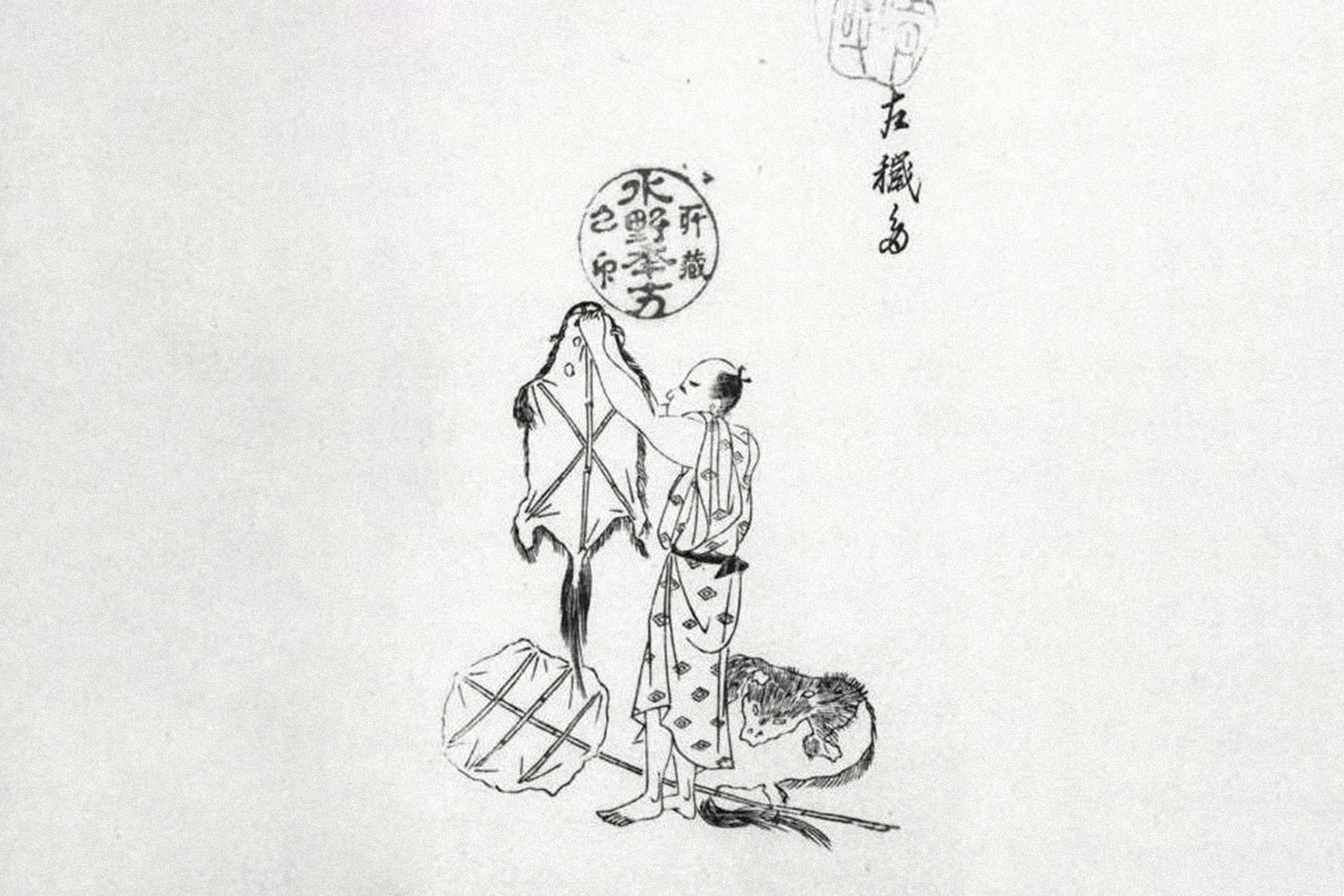

Under one Danzaemon, the Hisabetsumin received a government monopoly on supplying the shogunate with horse and cow hide, the production of lamp and candle wicks and control over monkey handlers. That may not sound like the pedigree of a “king” but you have to remember that leather was the primary component in the production of Japanese armor. And while monkey handlers did perform on the streets for the entertainment of the masses, they also often worked in stables as it was believed back then that the presence of monkeys kept horses from getting sick. So with an outcast army under their control supplying samurai with armor material and keeping their rides healthy, Danzaemon chieftains soon became indispensable to the shogunate and, therefore, became wealthy.

Underworld Or Not, It Was Good to be the King

In a nutshell, feudal Japan used to measure the wealth of entire provinces through their rice yields, called koku. To be considered a daimyo, meaning a powerful feudal lord, one needed to rule over a domain worth 10,000 koku or more. At the height of their power, the Danzaemon fortune was estimated at around 50,000 koku.

Danzaemon chieftains may have all been Eta themselves, but their position came with a lot of perks. The official Danzaemon residence was located roughly where the Asakusa High School in Tokyo stands today. Nothing of it survived to modern times, but back in the day, it was a thing to behold. Hidden away from mainstream Edo, the entire complex was occupied by up to 400 people and included private residences, warehouses, factories, a Shinto shrine, a courtroom and a prison. Danzaemon received permission from the government to adjudicate over every legal matter between the Eta and Hinin, including the right to imprison them at his discretion. For the service of keeping “the riffraff” in check, later holders of the Danzaemon name were also granted the right to ride in palanquins, wear silk, and even carry swords like samurai.

“Nihonbashi bridge in Edo,” part of Katsushika Hokusai’s “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” series

The Humble Origin and Limits of the Danzaemon Dynasty

The original Danzaemon (whose name each of his successors adopted) was most likely a wealthy Eta leather procurer from the late 16th century who fought for the title of chieftain with the more powerful Tarozaemon. However, Tarozaemon was backed by the Later Hojo clan, and when their rival Tokugawa family came to power at the beginning of the 17th century, most people associated with the Hojo became persona non grata. That left Danzaemon as the only candidate to deal with the influx of Eta and Hinin migrating to Edo, and so he was granted a certificate of authorization from Tokugawa Ieyasu, giving him dominion over the Hisabetsumin. But not all of them.

In 1708, a puppeteer Hinin sued Danzaemon for disrupting one of his shows and won the case. Due to the quirks of the Japanese legal system, this was interpreted as puppeteers and other theater performers such as kabuki actors being freed from Danzaemon’s control. In fact, Sukeroku (The Flower of Edo), one of the most popular kabuki plays ever, is said to have been written in celebration of kabuki actors no longer being beholden to Danzaemon. The Eta chieftains also couldn’t wrangle Edo’s blind bankers under their control because of their claim to a royal heritage. One Danzaemon tried to counteract it with a similar tactic, using a faked document supposedly linking him to the Hata clan that descended from China’s Qin Dynasty, but no one really bought into it.

Stepping Off the Underworld Throne and Into Fine Leather Shoes

The untouchable classes such as Eta or Hinin were officially abolished in 1868 during the Meiji Restoration, though societal animosity towards them remained and still occasionally rears its ugly head. However, as there was officially no more Eta, Danzaemon XIII became the last Eta chieftain after the government officially elevated him to the status of common citizen. He then changed his name to Dan Naoki, partnered up with an American tanner named Charles Henninger and spent the rest of his life promoting Western-style leather shoes in Japan.