Story by Merin Waite

Photos by Paul Quayle

“I am humbled that people, of Hiroshima, who suffered so much, are not bitter or vengeful.”

—Bishop Desmond Tutu

It was the weather that ultimately brought “Little Boy” to southwest Honshu. The shimmering heat and clear skies over Hiroshima in the summer of 1945 determined that it, as opposed to other considered targets such as Niigata, was chosen as the city on which the first atomic bomb was to be detonated. Thus, on Aug. 6, at 8:15 a.m., the bomb exploded next to Aioi Bridge over Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotions Hall, the remains of which have become the central feature of Peace Memorial Park.

Of course, it wasn’t the weather which initially put Hiroshima in the minds of Allied Forces military planners. The city had played an important part in the War both as a manufacturing center and a point of embarkation for troops being posted overseas. Its importance wasn’t surprising, given its historical association with armed conflicts.

In both the Sino-Japanesc and Russo-Japanese Wars, it played a significant role and had, in the Sino-Japanese War, even been the Emperor’s Military Headquarters for a brief period. But finally it wasn’t its role in the war effort that determined its fate but the relentless blue skies and sunshine that made it an easy target for the crew of the Enola Gay as they flew through the brilliant summer morning.

The immediate effects of the explosion came in two waves; first the radiant heat, then the shock. The radiant heat was such that everything burnable within a one-kilometer radius was reduced to ashes, even the roof tiles of the houses were blistered by its intensity. The shock wave that followed leveled most of what remained.

With a force of some five tons per square meter, even solid slabs of stone were moved, and few buildings were made of such materials in a district largely given over to small businesses and entertainment establishments. The longer term effects of the bomb were as grim if not as dramatic: cancer, unhealing burns and radiation sickness added to the usual impairments of bombardment and the cost in terms of bereavement, disorientation and despair are impossible to calculate.

Post-war Japan isn’t noted internationally for the beauty of its cities. Necessity made certain that whatever was needed went up despite how it might appear aesthetically, and rightly so, considering that people were homeless. Hiroshima looks very much like any other Japanese city in many respects but, by virtue of the far-sighted actions of one of Hiroshima’s post-war mayors, Shinzo Hamai, something of the city’s past has been preserved: the A-Bomb Dome.

Arrested in decay by restoration funded by a nationwide collection started in a Tokyo park, the remains of Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotions Hall stands as a warning against atomic war. It is fitting that, amidst Hiroshima’s urban modernness— parking towers, baseball stadium and department stores—there should be such a stark reminder of an event that leveled the city not 50 years ago.

Although the A-Bomb Dome is all that remains of original buildings in the vicinity, it is far from being alone in a park well supplied with monuments to those who died. A Cenotaph houses the names of all those killed as a result of the bombing, and to date the total stands at 176,964. More names are annually added to the register.

In front of the Cenotaph is Peace Pond, symbolically providing the souls of the dead with fresh, cool water. In the middle of Peace Pond is the Flame of Peace to be kept alight until all nuclear weapons have been abolished.

Nowadays all these monuments are constantly visited by school groups and it is bewildering to think their contemporaries of 48 years ago were among the victims of the explosion. Piteously burned, they staggered around crying for water on the same ground where school children play today.

Another place popular with the young is the Children’s Peace Monument. Some years after the bomb, many children developed leukemia and subsequently died. One such child made hundreds of paper cranes in the hope these symbols of good fortune would aid her recovery. Despite her persistence, she died and the monument was built to her memory. It is usually bedecked with chains of paper cranes left by children and adults who visit the memorial.

The park contains oddities and small monuments that might be missed by the casual visitor. Along the banks of the Motoyasu River are tablets commemorating the workers who toiled in small companies that formerly existed on the water’s edge. On the Han River is a monument to 20,000 Koreans said to have died. These people were doubly unfortunate as they were not living in Japan voluntarily, but as conscripted laborers.

The Korean monument was put up in 1970 and it is felt by some this was a rather tardy recognition of the suffering of those who died far away from their conquered homeland. Oddities include a slab of granite from Ben Nevis in Scotland given in the “spirit of peace” and, again on the Motoyasu River, a stone erected by the barbers of Hiroshima, extolling the spirituality of hair.

Perhaps hair, with its regenerative qualities, isn’t such an inappropriate thing to be extolled in Peace Park because, although overshadowed and rightly so by the past, the park isn’t all gloom and despair. In spring, the cherry blossoms are magnificent and hanami parties are just as much enjoyed here as elsewhere. Ample shade and seating make it an attractive location for young couples as well, but it is the past that truly gives the park its meaning.

Far more touching than the young are the old who come to the Cenotaph to pray or visit the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound (housing ashes of unidentified victims) and linger a while, lighting a stick of incense or offering a vessel of water. For them, the atomic bomb isn’t a few pages in a history book; it’s a remembered reality, albeit a distant one.

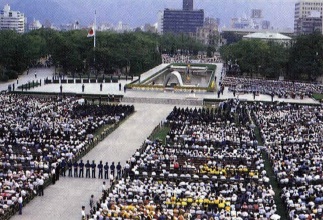

It must still be the same for most of the dignitaries who, once a year, attend the Aug. 6 ceremony to commemorate the epoch-beginning event. Almost overpowering in its media-oriented scale and organization, the occasion’s dignity is maintained when, for one minute at 8:15 a.m., complete silence is maintained.

In the intense heat characteristic of summer in Hiroshima, the only sound to be heard in the park is that of the cicadas. The thousands gathered are, to a man, silent; contemplating an event that slips every year further and further into the past but still lurks, threateningly, just beyond the present confines of peaceful, ordered societies.

In the evening of the 6th another ceremony is held, completely different from the morning’s display of politicians and officials. Toto-nagashi, or the lantern ceremony, is a far more personal affair. In it lanterns are set afloat in the Motoyasu River and allowed to drift out towards the sea. The symbolism of the floating lights is that of the souls’ progress in the spirit world.

As one watches the colored lanterns making their erratic progress downstream to the sound of Buddhist sutras, it is difficult not to reflect on the children, wives, husbands and lovers whose lives were so abruptly halted or hideously altered one summer morning. The bobbing lights float on under the bridge and down the river where most are snuffed out or snagged on the banks before they have gone far.

The atomic bomb has its apologists and it would be naive to suggest it wasn’t arguably a justified action, but on Aug. 6, it is far more important to forget the carping of politicians and the straightjacket of jingoism and instead concentrate on the tragedy that took place.

It is a time to reflect on suffering and heroism, on the sacrifices and personal tragedies and, eventually, the renewal of hope; a time to take seriously the message inscribed on the Cenotaph: “Let all souls here rest in peace; for we shall not repeat this evil.”

Near the front of the A-Bomb Dome stands a small monument to a Hiroshima poet called Tamika Hara who committed suicide in 1951. On it is written a short poem of his:

Engraved in stone long ago

Lost in the shifting sand

In the midst of a crumbling world

The vision of one flower.

For the people who loved and lost in this holocaust, the poem seems particularly apt. That they were able to build something from their crumbling worlds without bitterness or vengefulness is indeed a humbling thought.