In this month’s List of 7, we’re looking at miscarriages of justice in Japan. Over the years, there have been several cases in which the defendant of a major crime didn’t receive a fair trial, so this list could have been longer. Much longer. Notable names not included are Shigeyoshi Taniguchi, Yukio Saito and Masao Akahori, all of whom were exonerated in the 1980s after being sentenced to hang. There’s also Masaru Okunishi, who spent 46 years on death row despite being acquitted in 1964 for lack of evidence. There are likely many more wrongful convictions we don’t know about.

One of the main reasons why there have been so many miscarriages of justice down the years is due to a lack of transparency regarding the interrogation of suspects. While the situation has improved, with video recordings being introduced, for years interrogators got away with treating the accused in any way they liked. Even beatings and threats were used to obtain a confession, the “king of evidence.” Forced to spend 23 days — often extended — in daiyo kangoku (substitute prisons) without charge, it’s no wonder so many admitted to crimes they didn’t commit.

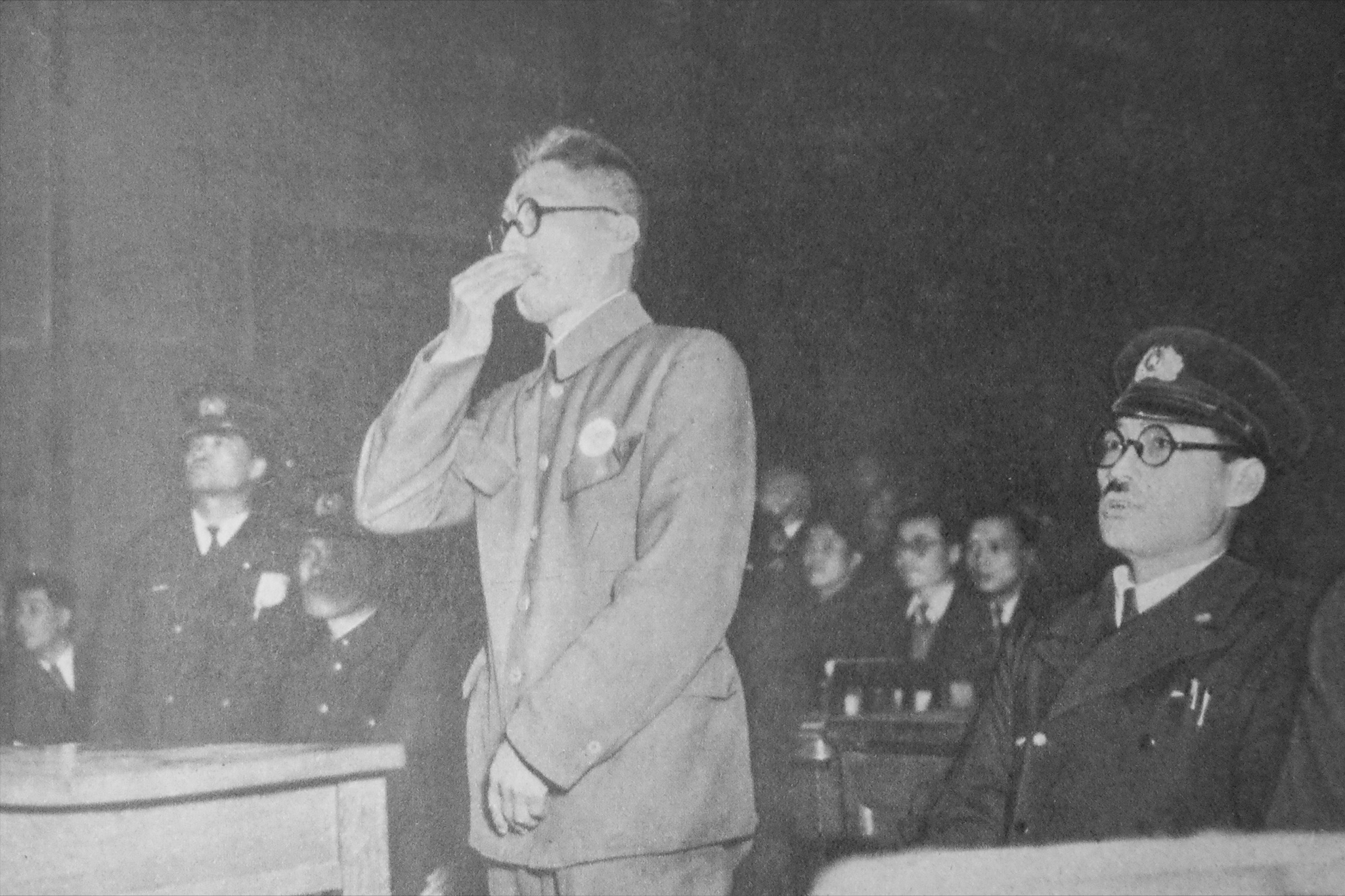

Sadamichi Hirasawa

1.

Sadamichi Hirasawa (The Teigin Case)

On January 26, 1948, a man claiming to be an epidemiologist walked into Teikoku Bank (known as Teigin). Identifying himself as Doctor Shigeru Matsui, he claimed he was sent by the US Occupation authorities because of a dysentery outbreak in the neighborhood. After seeing his identification, all 16 people inside believed him and subsequently took the supposed antidote he gave them. Twelve people died as a result. The poisoner then disappeared with ¥160,000, but strangely left ¥180,000 behind. It wasn’t the real Shigeru Matsui, though, as he had an alibi.

The police, instead, tracked down tempera painter Sadamichi Hirasawa, who had received a business card from the doctor. Tortured, Hirasawa eventually confessed to the crime. The defense argued that his admission of guilt was unreliable as he suffered from Korsakoff psychosis, an amnestic disorder, yet he was still sentenced to death. Many felt he’d been sacrificed to protect researchers from Unit 731, Japan’s covert wartime chemical and biological weapons division. No justice ministers were prepared to sign his death warrant due to doubt over his guilt. Hirasawa eventually died of pneumonia in prison aged 95.

Sakae Menda (center) at a rally against the death penalty in 2007

2.

Sakae Menda (A Double Homicide in Hitoyoshi)

In the same year as the Teigin Case, Sakae Menda, then aged 23, was charged for stealing rice. It should have just been a slap on the wrist. Things became complicated, however, when he was asked about the savage slaying of a Buddhist priest and the priest’s wife in Hitoyoshi, Kumamoto Prefecture. Menda, an illiterate black market rice dealer, said he’d been with a teenage prostitute on the day of the killings. The teenager had been paying protection money to the police. They allegedly made her testify that she’d met Menda on a different day.

In his diary, Menda claimed an interrogator threatened to “break his head with a 1.8-liter glass sake bottle” if he didn’t admit to the crime. As well as being beaten with a bamboo stick, he was also starved of food, water and sleep. Menda sought a retrial six times after being sentenced to death in 1950, and the case was eventually reopened in 1979. Four years later, he became Japan’s first death-row prisoner to be released. Given ¥700 for each day he spent in prison, he donated half to a group campaigning for the abolition of the death penalty.

3.

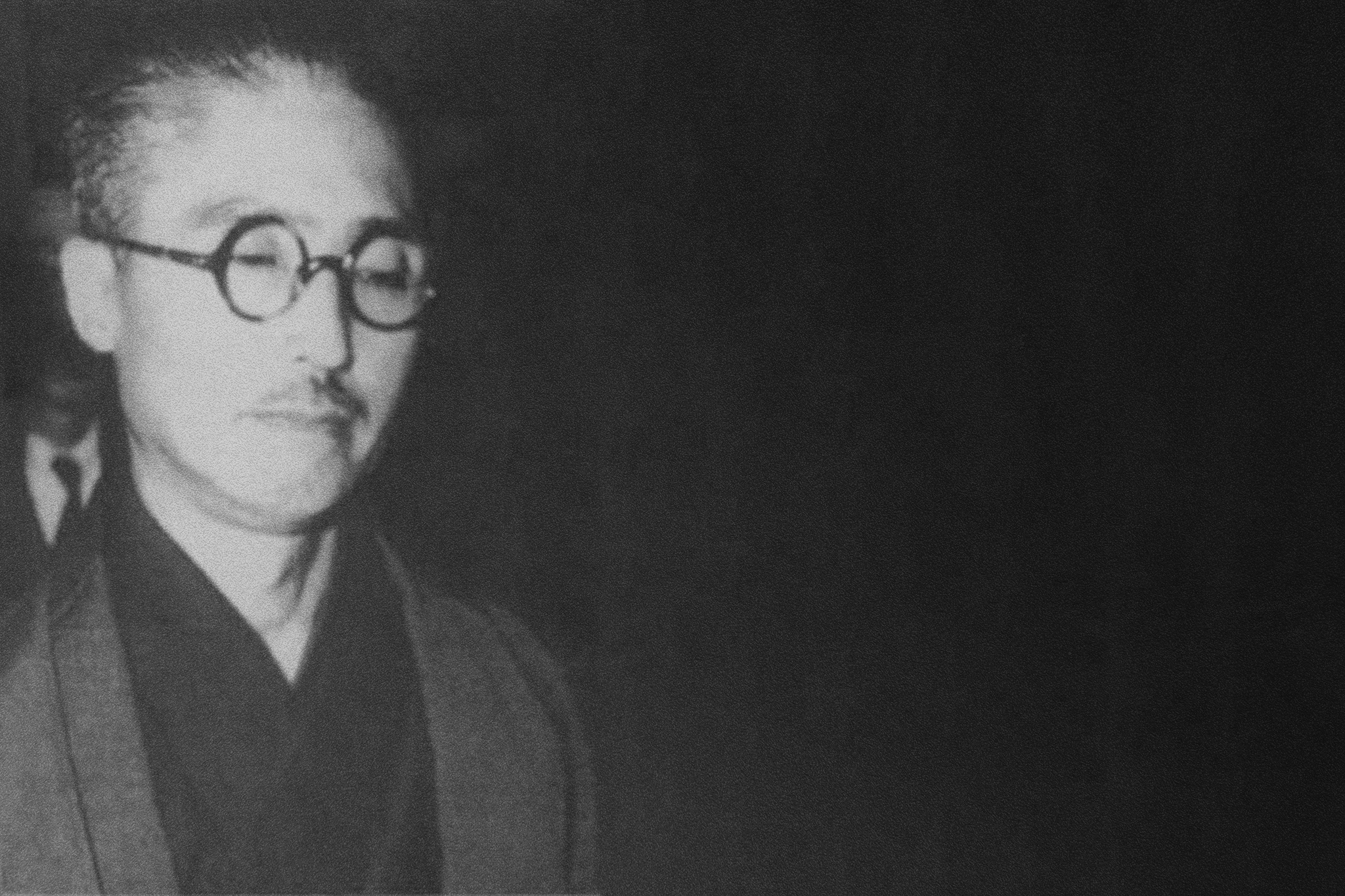

Matsuo Fujimoto (Attack on a Local Official in Kumamoto)

Between 1948 and 1972, segregated leprosy patients in Japan were tried in special courts outside standard courtrooms, a practice that the Kumamoto District Court later ruled discriminatory and unconstitutional. During that period, there were more than 90 trials held at sanatoriums and other facilities, including one that led to the execution of Matsuo Fujimoto in 1962. Charged for murder 10 years earlier, his trial emphasized the stigma surrounding leprosy in Japan at the time. Judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys wore protective clothing, and all evidence materials were handled by tongs.

Fujimoto was initially accused of throwing dynamite into the home of a local official who supported the segregation of people with leprosy. Despite having little evidence, police believed it was a revenge attack by the leprosy patient. Fujimoto was detained at the notorious Kikuchi Keifuen Sanatorium, but escaped on June 16, 1952. Three weeks later, the local official whose home had been the subject of the dynamite attack was discovered stabbed to death. The supposed murder weapon was found 10 minutes from the scene of the crime with no traces of blood. Thousands signed a petition demanding Fujimoto get a fair trial, including future Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone. It didn’t happen.

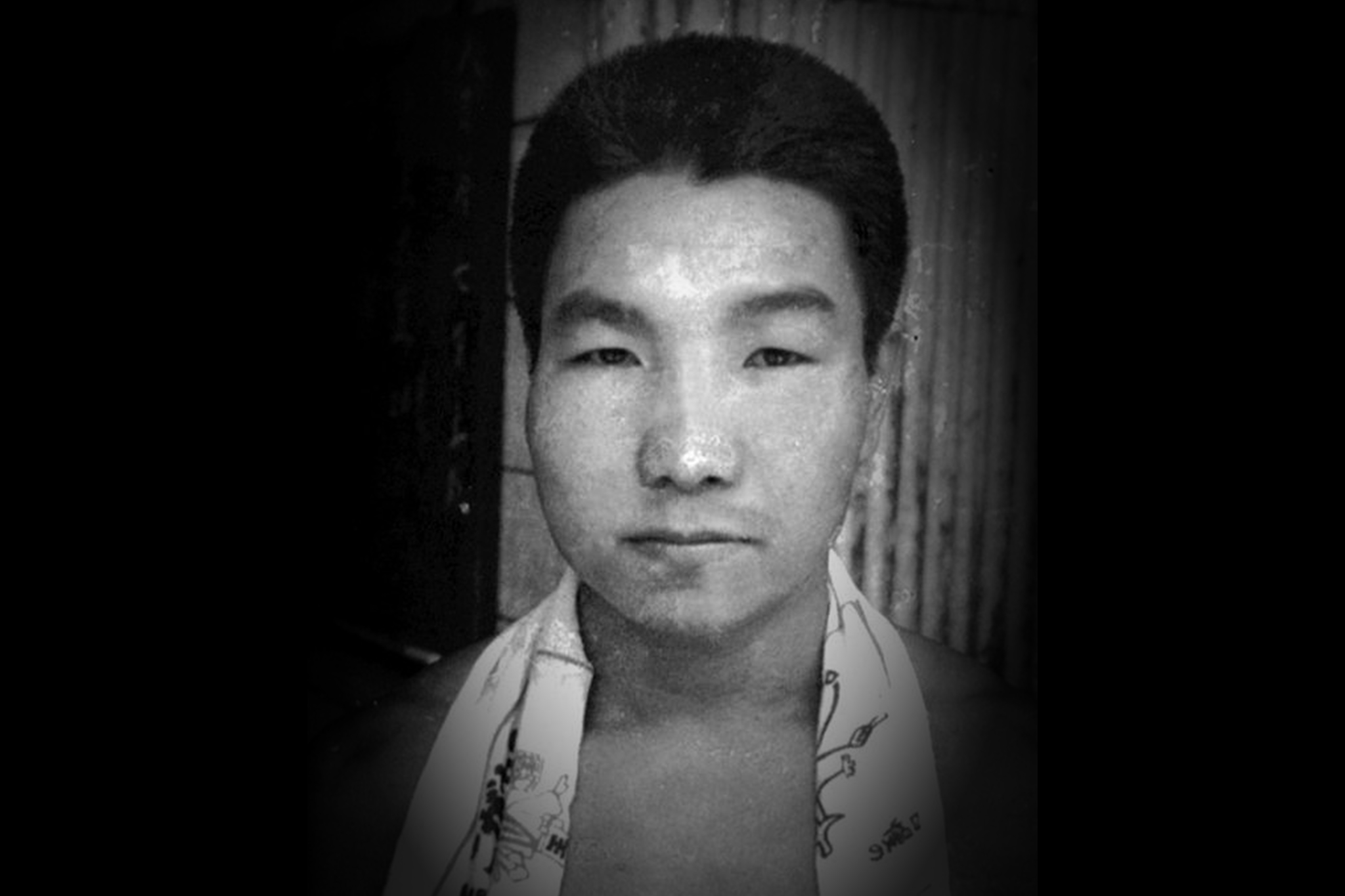

A young Iwao Hakamada, courtesy of Kyodo

4.

Iwao Hakamada (A Quadruple Murder Case in Shizuoka)

In 2023, Iwao Hakamada was granted a retrial more than five decades after his arrest. The former boxer, who was certified as the world’s longest-held death row inmate in 2011, was sentenced to hang for a quadruple murder that took place in 1966. At the time, Hakamada was working at a miso factory. He was accused of killing his boss along with his boss’s wife and two children in their home in Shizuoka Prefecture. They were discovered stabbed to death after a fire. Around ¥200,000 in cash was also stolen from the residence.

Hakamada was part of the team attempting to extinguish the fire. He then became the chief suspect due to what the police said were small traces of blood and oil found on his pajamas. Following 23 days of intense interrogation, which included threats and beatings, he confessed. No lawyer was present. In 2008, DNA tests showed that the blood on the clothing used as evidence didn’t match his. In 2014, he was finally released and granted a retrial. This decision was overturned by the Tokyo High Court before the Supreme Court stepped in. He now seems certain to clear his name.

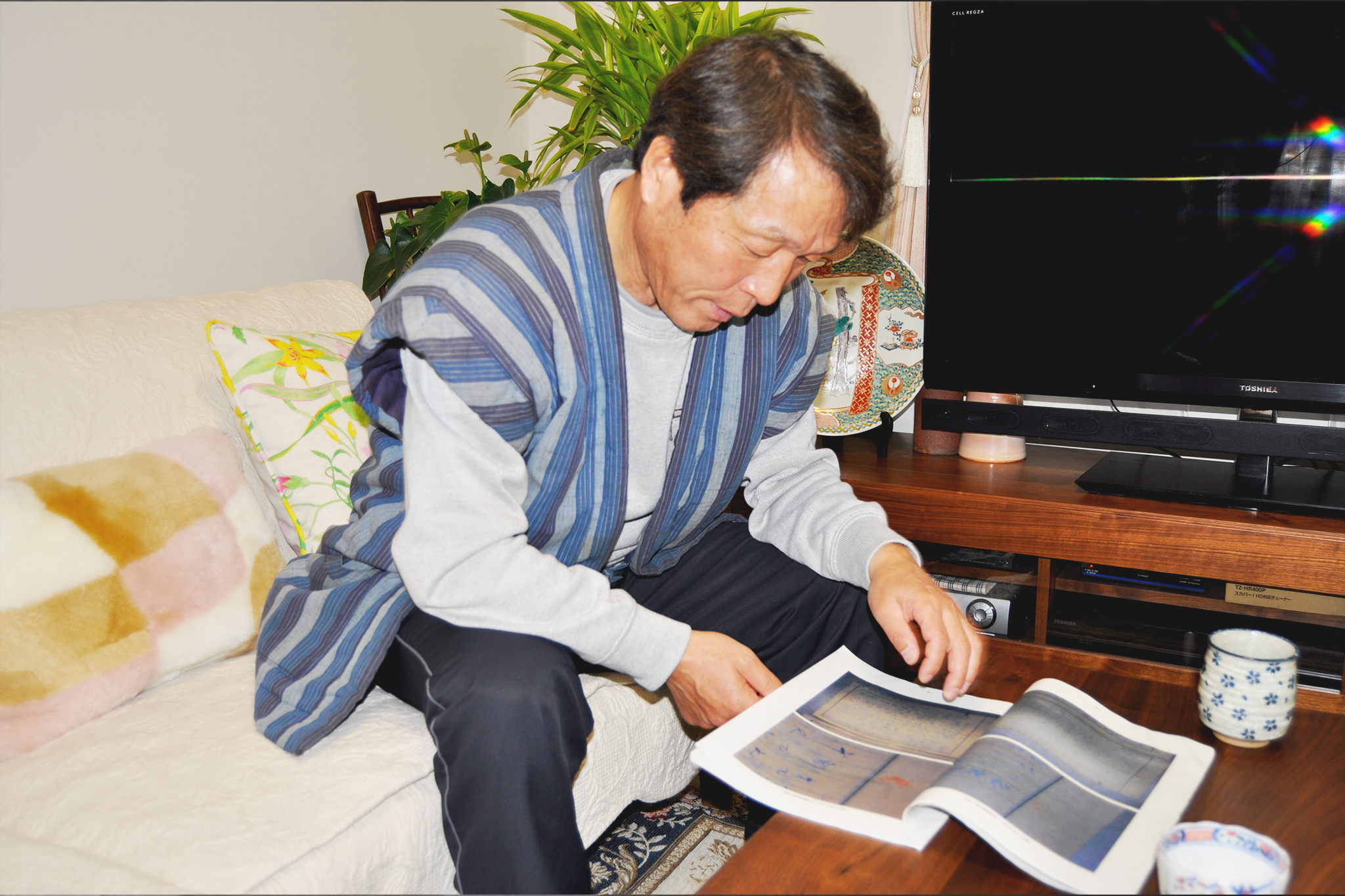

Shoji Sakurai, courtesy of the BBC World Service

5.

Shoji Sakurai and Takao Sugiyama (The Fukawa Incident)

You’d think spending 29 years in prison for a crime you didn’t commit would make you bitter and resentful. Yet, Shoji Sakurai is anything but in the 2022 documentary film Ore no Kinenbi (My Anniversary). Directed by Kim Sung Woong, who’s made several movies related to miscarriages of justice, it’s a surprisingly uplifting story about a 75-year-old man with terminal cancer who describes himself as a “singing, talkative, falsely charged victim.” It begins with him visiting the Chiba prison where he was incarcerated. “Ah, this brings back memories,” he says. “Many parts of myself were forged here.”

Sakurai was arrested with his friend Takao Sugiyama in 1967 on suspicion of robbery and murder in Fukawa, Ibaraki Prefecture. The case against them was built around unreliable eyewitness testimony and inconsistent confessions from the two men, given under duress. Their life sentences were finalized by the Supreme Court in 1978. “We were delinquent youths thinking nothing about life or tomorrow. But I didn’t kill anyone,” stated Sakurai, who penned more than 200 poems while in prison. The pair were exonerated of all charges in 2011. Sugiyama passed away four years later.

6.

Toshikazu Sugaya (The Ashikaga Murder Case)

On May 12, 1990, 4-year-old Mami Matsuda went missing from outside a pachinko parlor in Ashikaga, Tochigi Prefecture. Her body was later discovered at a nearby river. After around a year and a half of investigating, the police thought they’d finally caught their man: kindergarten bus driver Toshikazu Sugaya, who shared the same blood type as the killer. The police also felt he fit the profile of an individual capable of committing such a heinous act. He was interrogated for hours at a time, sometimes violently. Denied access to food, water and a lawyer, he confessed to the crime.

Sugaya was eventually acquitted in 2009 thanks to award-winning journalist Kiyoshi Shimizu, who discovered that parts of his confession were impossible and that the DNA testing method was imprecise. According to Shimizu, there was also enough evidence to convict the real criminal, however, the statute of limitations had passed. It is believed that the real perpetrator was also responsible for the murders and kidnappings of four other girls between 1979 and 1996: Maya Fukushima, 5; Yumi Hasebe, 5; Tomoko Oosawa, 8; and Yukari Yokoyama, 4. Missing for 27 years, Yokoyama is treated as a disappearance case.

7.

Govinda Prasad Mainali (The Murder of Yasuko Watanabe)

“I wanted to put my daughters on my lap and play with them. I was deprived of my youth, the most important time of my life,” said Govinda Prasad Mainali on his emotional return to Japan in 2017. The Nepalese man was finally granted his freedom in 2012 after spending 15 years in prison for a murder he didn’t commit. He was accused of raping and then killing Yasuko Watanabe, a 39-year-old senior economic researcher at Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) who was also doing sex work at night, in Tokyo’s Harajuku district on March 9, 1997.

Watanabe’s strangled body was discovered in her apartment 10 days later. Mainali, who lived in the adjoining building and knew the victim, was considered the prime suspect based on circumstantial evidence. The fact that the saliva discovered on her breast was known to be of O-type blood while Mainali has B-type blood wasn’t presented as evidence at the trial, and he was subsequently handed an indefinite prison sentence. In 2011, however, DNA testing proved that semen recovered from Watanabe’s body was not Mainali’s. Formally acquitted in November 2012, he was awarded ¥68 million as compensation but received no apology.