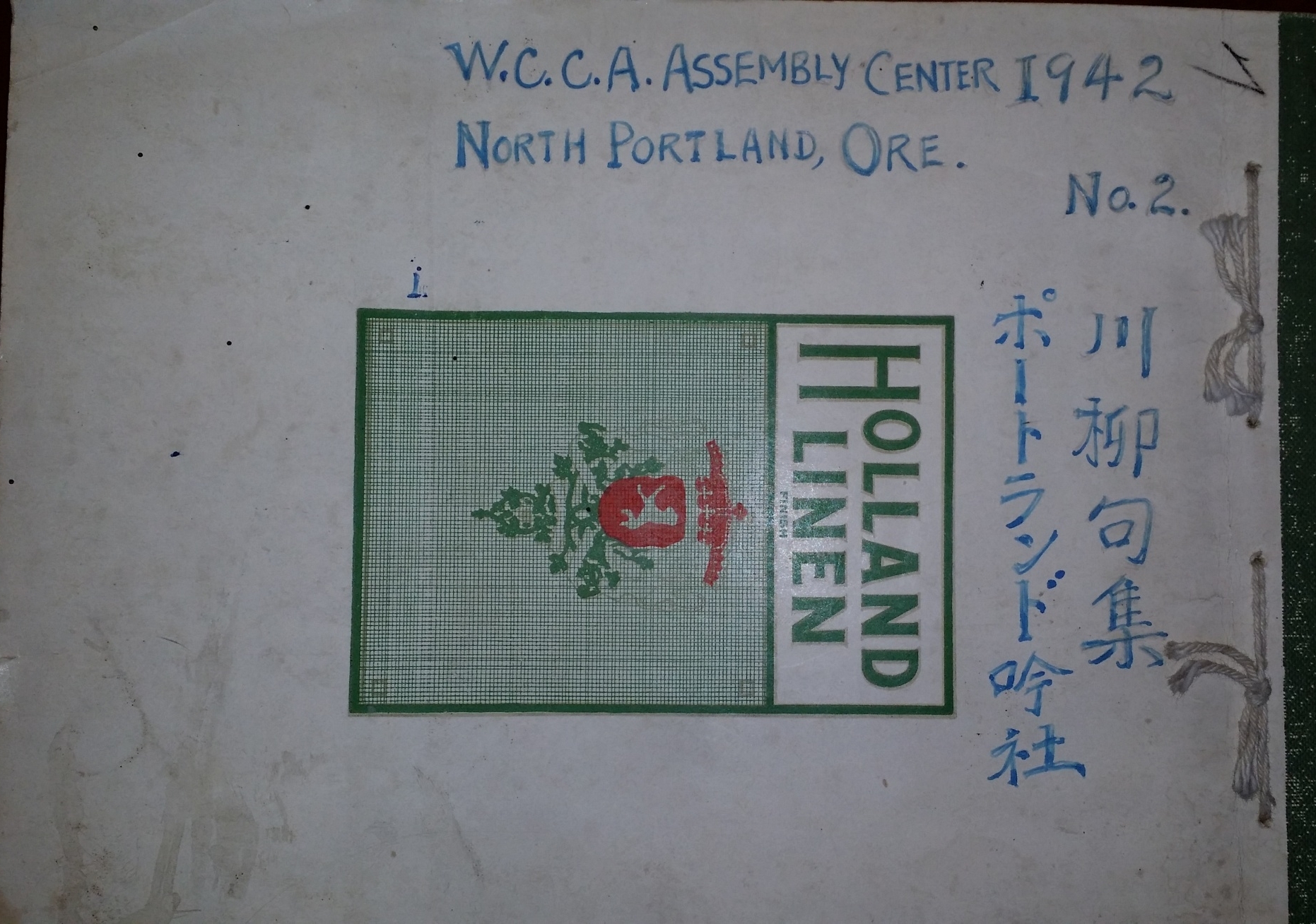

An old manuscript in Japanese that Duane Watari, a third generation Japanese American, happened to find in the basement of his mother’s house in the U.S., turned out to be historically significant. It was the first in a series of serendipitous events that led to the publication of They Never Asked: Senryu Poetry from the WWII Portland Assembly Center in June 2023.

Chance Encounters

When Watari discovered the manuscript that belonged to his grandfather, Masaki Kinoshita, it was among numerous boxes, diaries and items set to be thrown out, so it was lucky that it held his attention. However, not being able to read Japanese, he sought help from Shelley Baker-Gard, the Haiku Society of America coordinator for Oregon.

In another instance of serendipity, Baker-Gard had just happened to meet data scientist Mike Freiling that same month. Freiling was visiting a Haiku Society event for the first time. Learning that he had a lifelong passion for Japanese poetry and wrote haiku, she decided to get the manuscript from Watari and dropped in unannounced at Freiling’s workplace.

“You’d think this only happens in movies,” Freiling tells me over a video call. He, like Watari and Baker-Gard, recognized the rare piece of history that was in front of him and knew he had to do everything he could to get this out into the world. He and his wife Satsuki Takikawa would go on to translate a selection of some 67 poems from the manuscript.

Santa Anita Stockyards

Poetry for the Pain

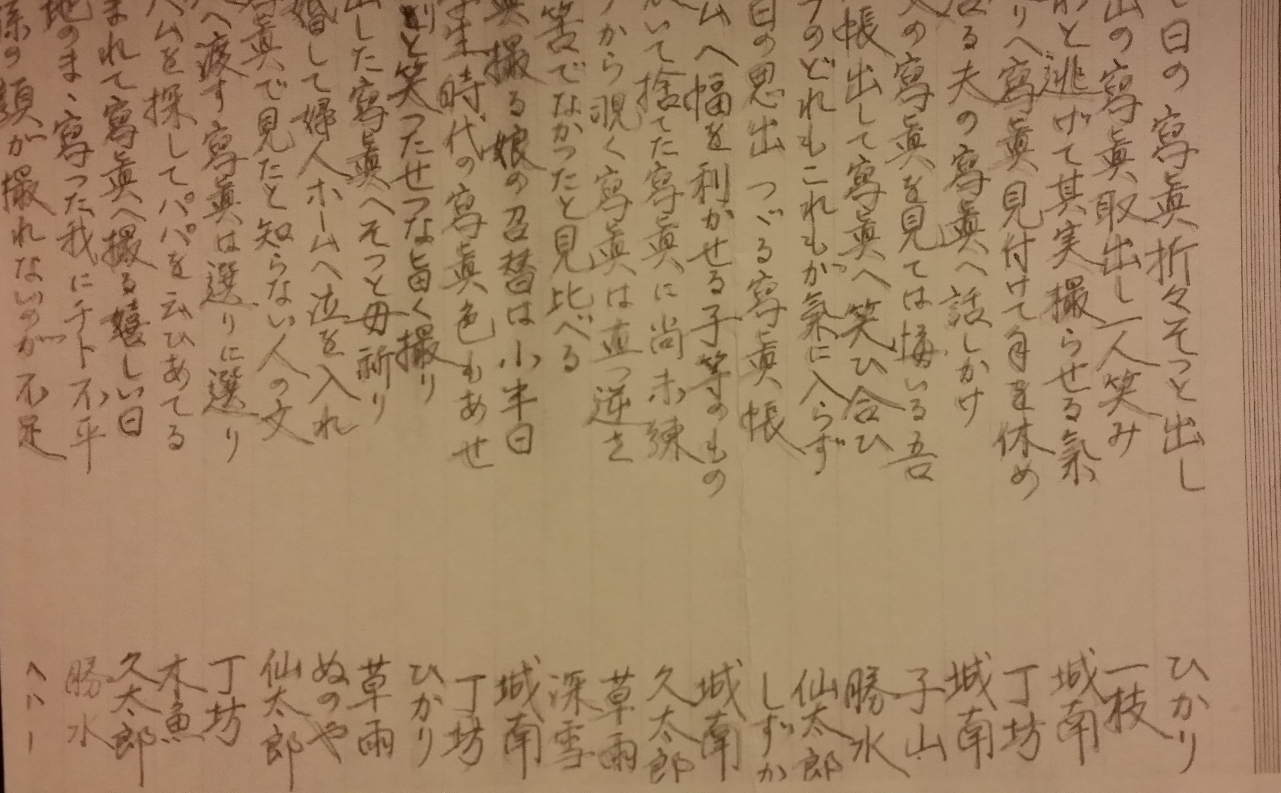

To understand the poignancy of this particular manuscript of poems, one must know the historical context. During the Second World War, Japanese Americans in the U.S. were removed from their homes and detained in internment camps. In Portland, Oregon, Japanese Americans were detained at the Portland Assembly Center and held until they could be sent to internment camps that were being built all over the U.S. It was here that Kinoshita, Watari’s grandfather, led a group of detained Japanese Americans to process their emotions through writing poetry. The poems he recorded are the manuscript that his grandson found more than half a century later.

Kinoshita, like many others in the manuscript, wrote under a pen name, which was Jonan. “Recording these poems must have entailed a certain amount of risk because the possession of documents written in Japanese was generally forbidden,” Freiling says.

The motivation to express one’s soul, despite the risks, reminds me of a well-known quote by German playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht: “In the dark times, will there also be singing? Yes, there will also be singing. About the dark times.”

The poems in the manuscript, which have the 5-7-5 form of a haiku, are in fact senryu. “Haiku tend to be meditative observations springing from the contemplation of nature. Senryu, by contrast, tend to be earthier, occasionally acerbic commentaries on human life, relationships and behavior (including misbehavior),” write Freiling and Baker-Gard in their joint essay published in Frogpond, the journal of the Haiku Society of America.

The book’s title comes from one of the poems from the manuscript:

they never asked

suspicious or not –

just put us away

By Sen Taro

This frustration over the injustice is present in many of the poems. Here’s one by the poetry group leader Jonan (Kinoshita) where he expresses the feeling of seeing the rest of the world free and carefree, not far away:

beyond the barbed wire

a glow of neon lights

stinging my eyes

These senryu poems let us peek into the hearts and minds of these people during a time of much suffering. They show a range of emotions, from fear and anger, to bitter humor and resigned acceptance. There’s also some hope of a better future and eventually leaving the detention center.

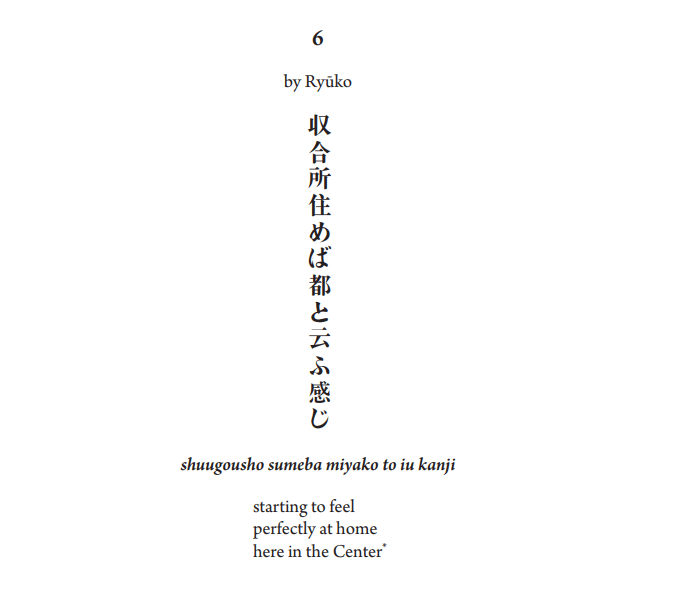

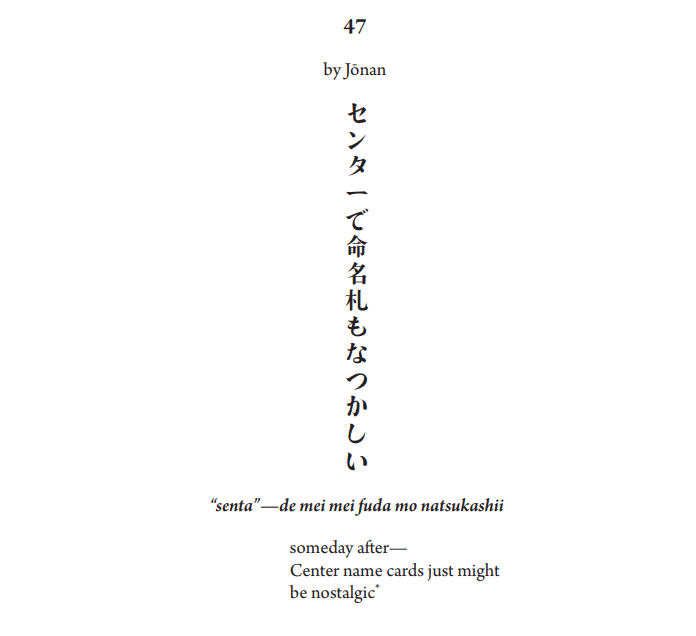

In coordination with the manuscript’s translators, here we present a selection of a few more senryu poems.

They Never Asked – Senryu Poetry from the WWII Portland Assembly Center

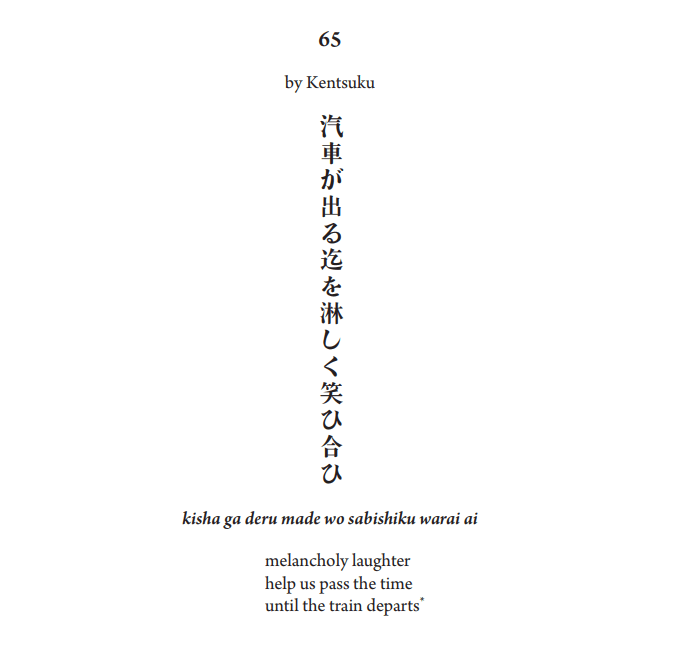

“This is the first poem that we looked at and it’s still perhaps my favorite. You can feel the anxiety implicit in the fact that the destination is unstated, and likely unknown at the time of its writing,” Freiling tells Tokyo Weekender when sharing his selections.

“The translation, ‘perfectly at home,’ doesn’t really do justice to this phrase, but it’s unlikely we would ever be able to find an English equivalent. Literally, the phrase means ‘if you live there, it is the capital.’ But the capital being referred to here is not just any old seat of government — it is Miyako — the ancient Heian capital at Kyoto, with its legacy of elegance and grace,” the translator explains.

“The translation, ‘perfectly at home,’ doesn’t really do justice to this phrase, but it’s unlikely we would ever be able to find an English equivalent. Literally, the phrase means ‘if you live there, it is the capital.’ But the capital being referred to here is not just any old seat of government — it is Miyako — the ancient Heian capital at Kyoto, with its legacy of elegance and grace,” the translator explains.

“Here, Jonan uses this paradox to great effect by performing a feat of poetic ‘time travel,’ casting the past into the present and the present into the future, so to speak, adding a hopeful and uplifting note to their current circumstances” Freiling writes.

Read more on Freiling’s blog and buy the book.