Kimekomi is a traditional technique that involves carving narrow grooves not much wider than a fingernail onto a surface such as soft wood or smooth foam, and then tucking fabric into these grooves. It can be used for simple ornaments and decorations, but perhaps the most popular artworks in the genre are kimekomi ningyo (dolls), in which case the technique is intricately employed to make the dolls’ clothes look true to life. The technique originated about 260 years ago, using leftover clothes from Shinto shrines and festivals. Most kimekomi dolls are seasonal – hina dolls are displayed in March, and gogatsu dolls (the samurai helmets for boys) are common sights at homes in May. We checked in with Toshimitsu Kakinuma, a second-generation kimekomi craftsman of the company Kakinuma Ningyo, to find out more.

What is a typical day like?

To make one doll, several people are involved – one craftsman doesn’t work on a piece from start to finish. Everyone has his or her part in the process, so the daily routine depends on the person. Generally, the order goes: someone will create the body by filing a wooden block into shape and fine-tuning the rough edges. The doll is then coated with a white paste, similar to what you use in Nihonga painting, which contains white pigment from seashells and nikawa (a kind of fish paste binder). Doing this helps preserve the doll. Glue is added to the carved-out creases, and the bits of fabric are then tucked into the doll using the kimekomi method. At our workshop the jobs are split up between about 30 people, but since most of us know the whole process, we can help each other out in a pinch. From first design idea to a finished product, it takes about two months. For the traditional hina dolls, we have to make everything – not just one doll. We make everything from the accompanying dolls in the set to the stage, as well as the background.

Why did you choose this job?

Well, my father is a registered traditional artisan of the kimekomi craft, and my brother works here too. I’m the second son and originally I worked elsewhere, but as some craftsmen started getting older and there was no one to take over, I decided to step in and join them. That was about 13 years ago now.

How do you become a kimekomi craftsman?

It’s mostly through self-learning. In my case I studied under a ningyoshi (doll maker) sensei elsewhere. Doing that doesn’t guarantee you’ll become a doll artisan though, as you need to start your own business and there’s not a large market. In the past, grandparents would buy hina and gogatsu dolls for their grandchildren when they were born, celebrating the new addition to the family and wishing them good health and a long life. Now, there are fewer children, so there’s less business and it’s hard for someone who chooses this path. The custom of giving gifts like this to grandchildren interests me, as it seems universal. I often ask people what their local tradition is – in France, grandparents give a silver spoon to their grandchildren. I hope the appeal of the kimekomi doll spreads and people across the world would consider it an addition to their home, as it adds color and warmth.

What’s the most important aspect of being a craftsman?

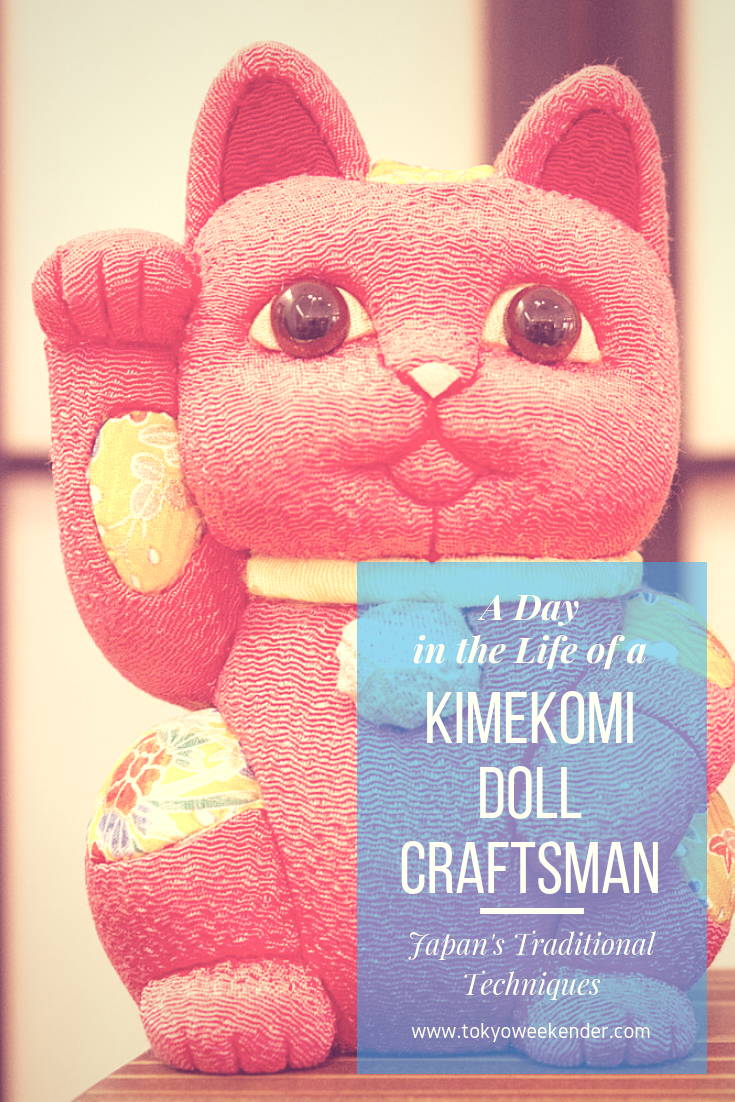

You have to be able to adapt to the needs of the current era. You’re still making something using a traditional method, but you need to adjust it to a modern lifestyle and environment. I think that’s important. We recently developed maneki neko (lucky cat) dolls, as it’s an item that can be sold year-round. With the cat shape as a base we can be quite creative with the fabrics, using imported ones for a modern look. We started with more orthodox colors, but as we’ve collaborated with different companies, we’ve created new and innovative designs. We also make kimekomi trays, which you can use to display your glasses, watches, or keys and so on. For this, we worked together with traditional craftsmen of Aizu-nuri (a form of lacquerware from Fukushima Prefecture).

What’s the hardest thing about being a craftsman?

Finishing a piece is of course a lot of work, and that’s difficult, but so is selling. You can’t just be silent and get on with your work – you also have to consider how to sell it. In the past, craftsmen only had to think about creating their products, but now we have to be marketers as well. Making things is important, of course, but you also have to be able to explain it. In the past, that was what wholesalers would do. They don’t really exist anymore and now that job falls on us as creators.

What’ s the best thing about being a kimekomi craftsman?

Kimekomi dolls change in appearance depending on the fabric you use. The color, the texture, the style – it all affects the final look and creates a unique piece. Choosing the fabric is a lot of fun.

Do you have any special memories from your career as a craftsman?

About two years ago, as part of the Tokyo Teshigoto Project, a group of artisans of various crafts gathered together and exhibited our products at Maison et Objet, an international trade fair in Paris. We sold items and also performed demonstrations of our work. One woman from England showed a keen interest in one of the maneki neko dolls, but the particular design she wanted was sold out. But since I had all the parts with me, I secretly went ahead and made that one on the spot. I gave it to her, telling her I’d made it for her, and she was so touched that she had tears in her eyes. I felt then that we had made a connection, and that creating things is a form of communication that transcends language.

Kakinuma Ningyo’s showroom is based in Saitama (1-21-11, Shin-koshigaya, Koshigaya-shi, Saitama). You can purchase dolls from the showroom directly, from their online shop, or from one of their Tokyo stockists. For their online shop and full list of stores go to www.kakinuma-ningyo.com/en/