As this month marks 50 years since the violent Shinjuku Riot (Shinjuku Sōran) of 1968, TW looks back on the events that led to it, and showcases the photographs of Hitomi Watanabe who captured the rebellion in a series of dramatic images.

On October 21, 1968, almost 290,000 demonstrators took part in protests across Japan to commemorate International Anti-War Day. Observed only in Japan, the anniversary began in 1966 when labor unions from 91 separate industries went on strike in opposition to the war in Vietnam.

On October 21, 1968, almost 290,000 demonstrators took part in protests across Japan to commemorate International Anti-War Day. Observed only in Japan, the anniversary began in 1966 when labor unions from 91 separate industries went on strike in opposition to the war in Vietnam.

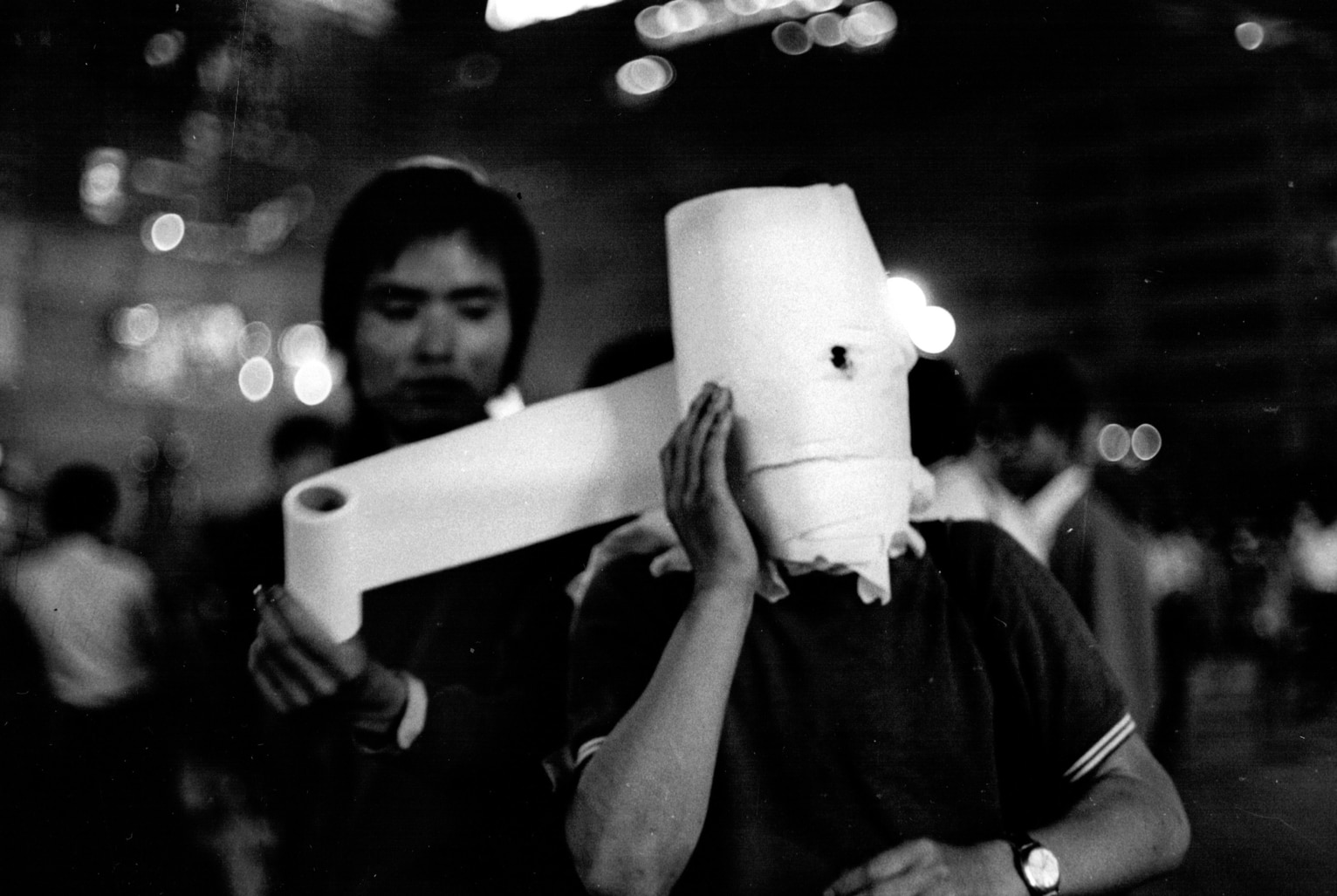

Of all the rallies that took place in 1968, the bloodiest and most memorable occurred at Shinjuku Station. Over 700 leftist agitators were arrested during the night after clashing with the police. Seats were thrown from trains, parts of carriages were set on fire and flames spread to the south exit of the station. Photographer Hitomi Watanabe was on the scene to capture the rebellion.

“One of the first things I remember was the police confronting and hitting demonstrators in front of the station”

“I spent a lot of time in Shinjuku, going to bars, enjoying the art scene, underground plays and taking pictures of celebrities,” Watanabe tells TW. “I covered peace demonstrations back then, but it was actually just a coincidence that I happened to be in the area at the time. When the trouble began I decided to start taking photographs. One of the first things I remember was the police confronting and hitting demonstrators in front of the station. A man who was standing next to me turned and said, ‘The police struck first, right?’ Looking closely, I then realized it was Nagisa Oshima.”

An iconoclastic director known for movies such as the sexually explicit In the Realm of the Senses and the Palme d’Or-nominated feature Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, Oshima was influenced by the student uprisings and urban counter-culture that emerged during the 1960s. This was apparent in Diary of a Shinjuku Thief, a 1969 arthouse film (shot during the troubles of 1968) that used cinema vérité techniques to convey the riotous atmosphere of the time. Another noteworthy film set against the backdrop of the student-led protests in Shinjuku was Toshio Matsumoto’s avant-garde cult classic Funeral Parade of Roses (1969).

Background: The Anpo Protests

At the forefront of many of the post-World War II demonstrations in Japan was Zengakuren (All-Japan Federation of Students’ Self-Governing Bodies), an organization with close links to the Japanese Communist Party that was founded in 1948. Despite initially intending to focus on educational issues such as high fees and university governance, the group became increasingly politicized in the 1950s as anti-war sentiment grew. This was fuelled by numerous factors such as the outbreak of the Korean War, and most notably the security treaty between the United States and Japan that was first signed on September 8, 1951.

The agreement, which gave America the right to maintain military bases on the archipelago and utilize its armed forces to suppress any domestic disturbances, was considered unfair and unconstitutional by many Japanese people. While the US pledged to defend Japan, there was concern that the bases left the country exposed to the possibility of a nuclear attack during the Cold War.

Although campaigners against these bases initially failed to mobilize masses nationwide, the movement started to gain momentum in 1957 when Nobusuke Kishi became prime minister. Described as “America’s favorite war criminal,” Shinzo Abe’s maternal grandfather immediately declared his intention to amend and ratify the security pact, which would further strengthen ties between Japan and the United States. Led by Zengakuren and the Socialist Sohyo Party, factions from both the left and right united in their condemnation of the revised treaty.

In spite of the efforts of thousands of students who occupied Haneda Airport in an attempt to stop prime minister Kishi from boarding his plane to America, the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between the United States and Japan, commonly known as Anpo, was signed on January 19, 1960. In May of that year, Kishi ordered the police to remove members of the Socialist Party by physical force from the National Diet when they staged a sit-in to try and prevent the pact from being ratified.

The brutal tactics employed by the government angered the public and strengthened the anti-treaty campaigners resolve. That summer thousands took to the streets in a number of high-profile protest rallies, and on June 10 President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s press secretary James Hagerty had to be rescued by a marine helicopter when his car was mobbed by protesters as he attempted to leave Haneda Airport. Four days later Tokyo University student and Zengakuren member Michiko Kanba was killed during a demonstration outside the Diet building.

Eisenhower’s state visit was canceled and Kishi was forced to resign. Shortly after, the former prime minister was attacked in his home by a right-wing extremist who stabbed him six times in the leg. Several months later, Inejiro Asanuma, head of the Japan Socialist Party, was assassinated by a 17-year-old rightist fanatic carrying a samurai sword as he gave a speech live on TV.

A Global Rebellion

The Anpo protests failed to prevent the treaty from being ratified and Zengakuren subsequently split into various warring factions. Over the next few years, students appeared to become increasingly apathetic to the cause as the economy continued to improve. The situation then changed dramatically in 1968, which was a watershed year in world history as protests erupted around the globe in cities such as Paris, Prague, Chicago and Rio de Janeiro to name but a few.

Revolutionary fervor soon gripped Japan as university students, influenced by what they’d seen from abroad, plus images of the Anpo protests broadcast on news programs, raised their voices, marched on the streets and barricaded themselves in classrooms. Armed with hard hats and sticks, they attempted to block the police from entering the student-occupied areas known as “Liberated Zones.”

Leading the way was Zenkyoto, a nationwide all-campus joint struggle council demanding various reforms to the country’s outdated educational institutions and the democratization of their own campuses. The movement, established by students from Nihon University and the University of Tokyo, wanted to put an end to corruption, poor lectures and the unfair punishment they felt was dished out at Japanese schools and universities. Watanabe was on site at the University of Tokyo as the students barricaded themselves in.

“My friend Michiyo introduced me to her partner Yoshitaka Yamamoto, one of Tokyo University’s Zenkyoto leaders,” says Watanabe. “That was how I got my foot in the door. That year I remember seeing various student demonstrations spreading all over Europe, but from what I heard, Japan was the only country where you could photograph what was going on inside the universities.”

Many students considered these university clashes as being part of a wider battle against the conservative, pro-American Japanese government and subsequently aligned themselves with New Left organizations. Anti-Anpo sentiment remained strong and The United States involvement in the Vietnam War further inflamed their anger. On August 8, 1967 tank cars carrying jet fuel bound for US air bases in Tachikawa and Yokota crashed into a freight train at Shinjuku Station, causing a fire on the tracks.

This was the trigger for the riot that took place at the same location the following year.

The 1968 Protest and Beyond

Around 2,000 people, including many university students and members of various New Left groups, gathered outside Shinjuku Station ready to cause havoc and destruction on the night of October 21, 1968. Encouraged by what they were seeing, many onlookers spontaneously decided to get involved. According to newspaper reports, the number of rioters exceeded 20,000 by the end of the night and more than 3,000 officers were sent out to try and stop them. For the first time in 16 years, the anti-riot law was applied, and 743 people were arrested. Trains eventually began running again at 10am the next morning.

Demonstrators weren’t discouraged by the arrests and continued to protest at Shinjuku Station – even a year later. Watanabe recalls the spring and summer of 1969 when a band of activist musicians known as “Folk Guerrillas” occupied the underground plaza linking the west and east exits. “Folk Guerrillas would sing every Saturday,” she says. “It started off small, but then each week the number of performers and people watching would increase. Eventually, the plaza was full. It was a much more peaceful atmosphere than what I witnessed the year before, even though the police tried to keep people moving.”

More protests occurred in 1970 when the security pact with America was renewed, however, since then there has been hardly any large-scale movement in Japan that has challenged the government or its policies. Between 2015 and 2016 the activist group SEALDs (Students Emergency Action for Liberal Democracy) emerged, organizing various demonstrations against the ruling coalition headed by Shinzo Abe. Their main grievance was with the controversial security bill, approved in the face of widespread opposition, that permitted the Japan Self-Defence Forces to be deployed overseas. The rallies were popular with the masses, though failed to make a significant or lasting impact. SEALDs disbanded in the summer of 2016.

“We are living in a very different world these days,” concludes Watanabe. “In 1968, you had the Vietnam War, the Prague Spring, the Paris demonstrations, the assassination of Martin Luther King, and all these world-changing events that helped to create this surge of student activism in Japan. Now we live in an electronic age, so I feel it’s less likely that such a huge movement will emerge. I wouldn’t say young Japanese people are completely non-resistant, but I do feel they are quite passive.”