On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake generated a massive tsunami that sent wave after wave crashing into Japan’s northeastern Pacific coast. These waves were responsible for most of the estimated 19,729 lives lost during the disaster. Over a decade later, 2,500-plus people are still considered missing, and only recently, the remains of a little girl lost to the ocean that day were recovered.

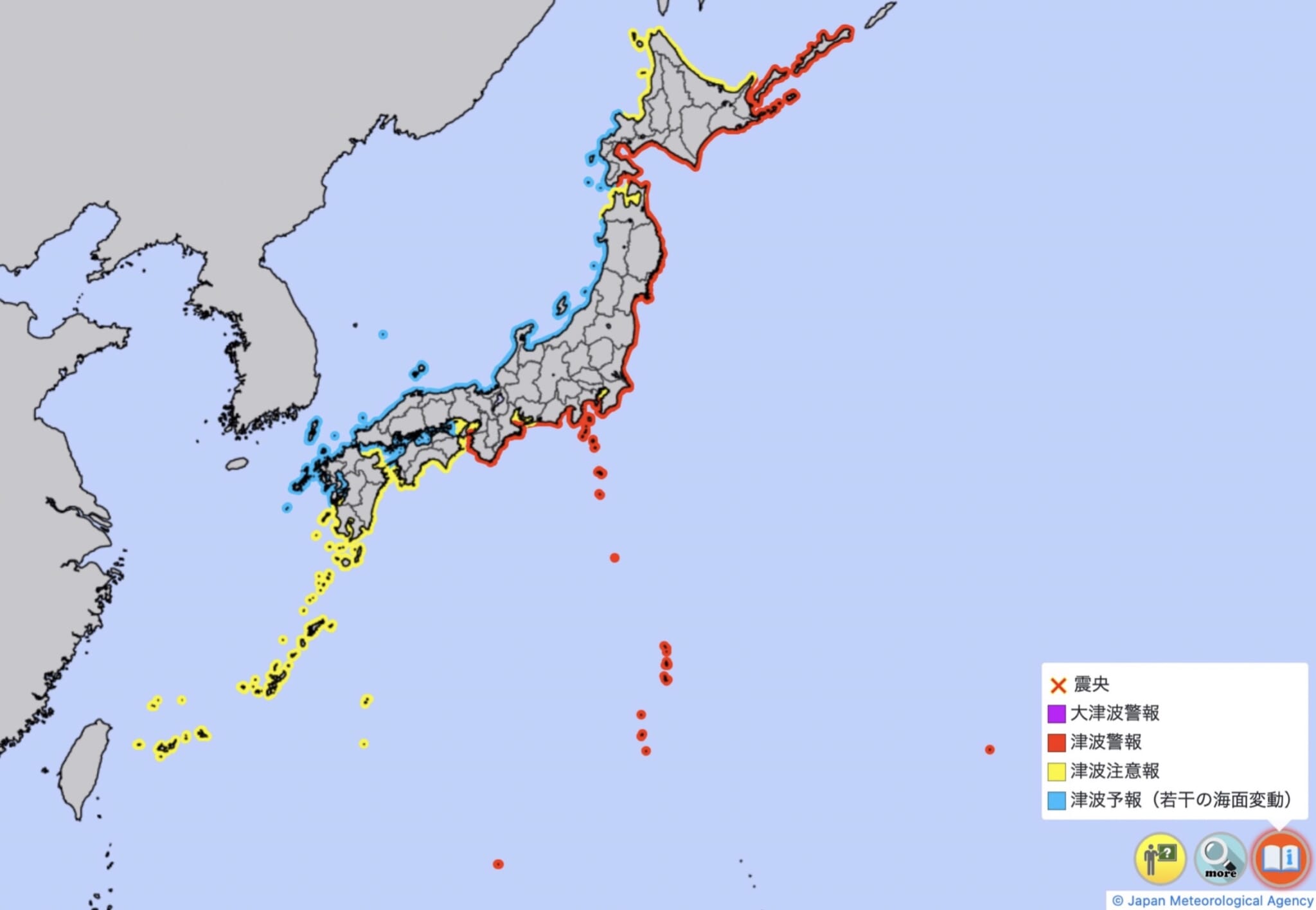

It was far from the first tsunami to hit Japan, and it hasn’t been the last; in recent years, the Sea of Japan coast experienced a tsunami following the 2024 Noto earthquake, while the 2025 Kamchatka earthquake resulted in tsunami warnings of various levels for the entire coast of Japan. For anyone living in or visiting Japan’s coastal areas, the risk of a tsunami is something to consider: If you heard a tsunami siren or announcement, or if you felt a large earthquake while near the seashore, would you know what to do or where to go?

With November being a prime month for tsunami preparedness practice (November 5 is World Tsunami Awareness Day), let’s use the occasion — or any day, for that matter — to explore tsunami: what they are, why they’re so dangerous and how to stay safe.

Tsunami evacuation route sign. Photo by DimiTalen, CC0 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=141598658)

Tsunami: What They Are and the Risks They Pose

In the World Risk Index 2025, Japan is ranked third in the “exposure” metric. This means that, out of 193 countries, it is third most likely to experience “extreme natural events and negative climate change impacts.” Solid government — plus social stability and strong emergency relief preparedness — helps it rise to 17 in the overall “risk” metric, but that doesn’t negate the need for individual emergency preparedness for natural disasters, whether flooding, landslide, tornado, earthquake, typhoon or tsunami.

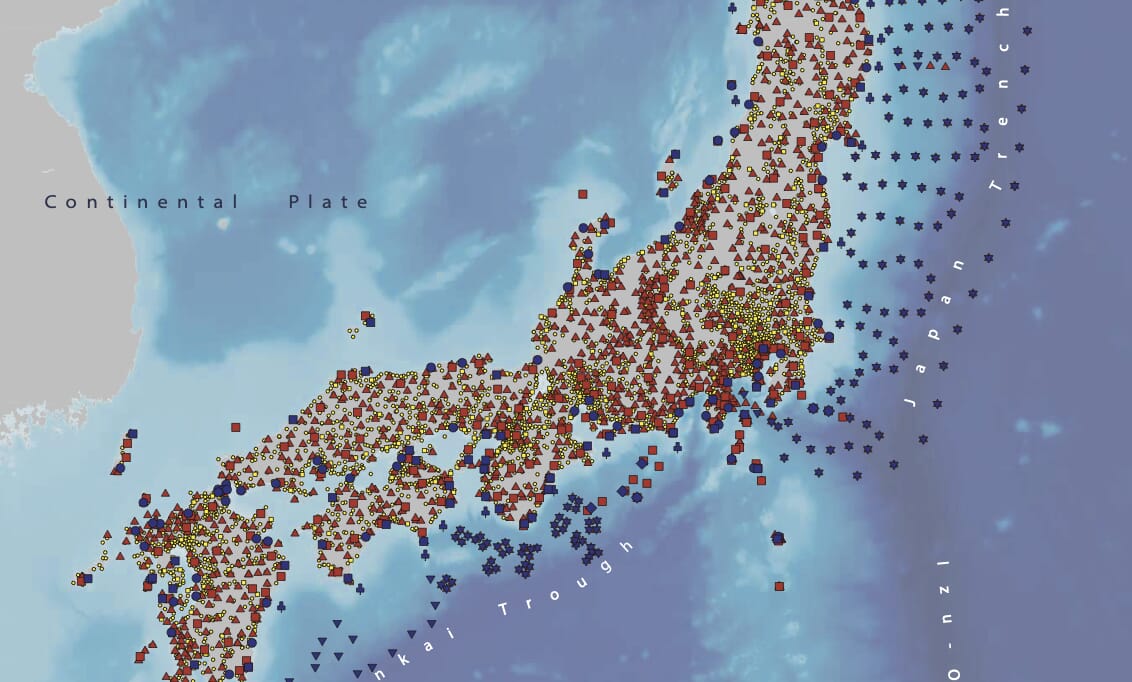

According to the United Nations, tsunami, while rare, surpass all other natural disasters in lives claimed, with 58 tsunami responsible for over 260,000 deaths — an average of 4,600 per tsunami — in the last 100 years. These destructive, fast-moving waves are caused by a variety of phenomena, including landslides, volcanic eruptions and, most commonly, earthquakes, which are responsible for just over 70% of all tsunami. With Japan a hot spot for seismic activity, it’s no surprise that the country sees more tsunami reach its shores than any other country on Earth.

Because the phenomena that cause tsunami displace enormous amounts of ocean water in an instant, the resulting waves are incredibly powerful. Unlike normal wind-driven waves, the entire water column, from seabed to surface, is affected.

In a tsunami wave train — the name for the multiple waves that make up a tsunami — wave intervals and heights are inconsistent; the largest wave may not be the first to reach the shore and may, in fact, take hours to arrive. Meanwhile, waves can be spaced out by anywhere from several minutes to several hours. From the first to the last surge, a tsunami can last more than a day.

Screenshot of tsunami warning for the 2025 Kamchatka Peninsula earthquake. Source: Japan Meteorological Agency via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=170991007)

Waves generated by tsunami are also much faster than your run-of-the-mill wave. While a wind wave can travel approximately 8 to 100 kilometers per hour, a tsunami wave can travel between 800 and 1,000 kilometers per hour in deep water and between 30 and 50 kilometers per hour in shallow water. At that speed, and with that amount of water, tsunami waves pack a much more serious punch. According to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, it takes just 15 centimeters of fast-moving water to knock an adult off their feet.

The danger doesn’t end at landfall, either: The retreat of tsunami waves can be even more dangerous than their arrival, as any vehicles, structures or debris caught in waves as they come in are dragged back out to sea, potentially colliding with people struggling to stay afloat and make their way to safety.

A portion of Japan’s earthquake and tsunami monitoring system. Cropped from an image used in “Earthquakes and Tsunamis: Observation and Disaster Mitigation” (Japan Meteorological Agency) (https://www.jma.go.jp/jma/kishou/books/jishintsunami/en/jishintsunami_en.pdf)

Early Warning Systems and Alerts

As dangerous as tsunami are, thanks to science and international cooperation, their arrival no longer comes as a surprise — usually. For earthquake-related tsunami, at least, seismic and water-level networks provide scientists with data they can use to predict whether a tsunami has been generated.

For tsunami caused by other phenomena, like underwater volcanic eruptions, it’s not as straightforward. But across the oceans, gauges, meters and buoys constantly monitor the seas.

Since the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004, cross-border cooperation has meant that information on tsunami dangers is shared quickly and widely. So, even if an earthquake occurs, for example, off the coast of Chile, tsunami information is relayed worldwide. Within minutes of the 2025 Kamchatka earthquake, tsunami alerts and coastal advisories of various levels were in place across the Pacific, from Japan and the Pacific Islands to countries along the west coasts of North and South America.

Tsunami buoy used by the United States’ DART (Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis) network. Photo by Chris Boyer on Unsplash

In Japan, alerts of all kinds are shared via J-Alert, a satellite-based emergency broadcast system that instantly transmits warnings to city loudspeakers, TVs, radios, registered email addresses, apps and cellphones. Foreign cellphones can receive alerts as well, though they need to be used with a SIM card or eSIM from a supported carrier, and emergency alerts need to be enabled.

For phones that don’t meet those requirements, a variety of apps providing warnings and valuable information on safety and evacuation are available, like Nerv Disaster Prevention, Yurekuru Call (App Store | Google Play) or Safety Tips, the app recommended by the Japan Tourism Agency.

NHK, Japan’s public broadcaster, provides alerts from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) via its NHK World-Japan app. NHK also has a number of on-demand programs that share essential disaster preparation information, including Navigating Disasters.

“To Future Generations: In case of earthquake, evacuate to an area higher than this.” Tsunami height marker in Minamisanriku, Miyagi Prefecture. Photo by Mizushimasea, CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=136548125)

If you’re traveling without a data or service plan (or pocket Wi-Fi) when disaster strikes, access your apps and websites disseminating emergency information by connecting to Five Zero Japan, a free public wireless LAN service provided by Japan’s major carriers during emergencies.

There’s no need to input a password or create an account, meaning access is immediate. However, to access Five Zero Japan, you’ll need to be in the vicinity of a mobile carrier Wi-Fi access point — think convenience stores, cafes, restaurants, shops, etc.

Unfortunately, some tsunami are generated so close to land that warning systems are unable to release information in time. Because of this, it’s essential to be aware of natural tsunami warning signs, like strong or long earthquakes. You might also hear a loud roar coming from the sea or notice that the ocean is behaving strangely; a sudden rising tide or ebb tide is a sign to head for high ground.

Staying Safe on the Ground

Emergency alerts, whether from your phone or the city’s loudspeakers, will tell you what to do next, whether that’s to vacate the water and coastal areas for tsunami advisories or, for tsunami warnings and major warnings, to evacuate to higher (and higher) ground. Remember that because tsunami are a series of waves, the safe high ground you initially find could become inundated by later waves.

Just as the seaside is dangerous, so are rivers and streams, which act as highways for ocean water to reach surprisingly far inland. During the Tohoku earthquake, tsunami waters penetrated 10 kilometers inland after flooding a river.

To help guide your escape, Japan’s seaside towns and cities provide basic elevation information and directions to emergency evacuation grounds, which you’ll find printed on roads, posts and information signs. It doesn’t hurt to take note of these — and any high ground or tall structures designated as Tsunami Evacuation Buildings — as you explore.

Some municipalities, like Kamakura in Kanagawa Prefecture, provide disaster preparedness information tailored to tourists, while others have general disaster preparedness resources for residents, such as the Tokyo Bosai manual, which includes detailed information on a variety of scenarios.

Don’t wait until disaster strikes to review the information provided; if you know you’ll be spending time in a coastal area, see what information you can find before arriving. With luck, your newfound knowledge will remain academic — but if the worst-case scenario occurs, you’ll be better prepared to get through whatever nature throws your way.

Consular Registration and Your Emergency Prep Checklist

In the event of a major natural disaster, it’s important for your home government to know where you are. Many countries offer a sign-up service for citizens traveling abroad, like the United States’ Smart Traveler Enrollment Program or Canada’s Registration of Canadians Abroad

Registering your travel information not only allows your government to provide you with emergency information for your destination, it also helps consular services know how many citizens might need support and how to contact them.

Of course, general travel advice and rules apply, too. Travel with your passport on your body at all times. Have embassy or consular contact information on hand and keep family and friends up to date on your travel plans. Also, make sure you have change or bills in small denominations to use at vending machines, and invest in a phone charger.

Most importantly, follow all instructions provided by local officials, evacuation area or shelter staff, and volunteers. With everyone’s cooperation, they’ll be better able to put Japan’s carefully considered protocols to work, saving lives and making a trying experience a little more bearable.

Related Posts

- How to Prepare for Natural Disasters in Japan

- An Essential Earthquake Survival Guide: How To Be Prepared for Japan’s Megaquake

- Japan Life Kit: Typhoon Season Dos and Don’ts

Updated On December 2, 2025