Several years ago, Kyoto was at a crossroads as the city pushed to adapt to the influx of foreign tourists. The sometimes-difficult process of pivoting to the needs of visitors over the expectations of domestic clients was playing out in shops, ryokans, and temples all over the city. It all came to a halt with the pandemic, but this era of rapid metamorphosis has been lovingly captured by Australian expat writer, director and cinematographer Felicity Tillack in her feature film debut, Impossible to Imagine.

Choosing to focus on a thin slice of life in a changing Kyoto, the film follows the shifting fortunes of Ami, the owner of a traditional kimono shop in a lesser-visited neighborhood in the center of the city. Her journey to adapt to the times is guided by Hayato, an outgoing outside-the-box business consultant who happens to be biracial. While first and foremost a love story, Impossible to Imagine is driven by the cultural conundrums that Japanese society seems uniquely gifted at inflicting upon itself.

Convincingly displaying the Japanese experience as a foreign writer is challenging but Tillack weaves a story with a confident, authentic tone. The genesis of the project began during her seven-month stay at a temple in Koyasan, Wakayama, where she discovered a unique duality that existed in the hearts of some of more devout residents of the mountain enclave. Drive and ambition weighed against faith and prayer, modern life at times clashing with traditional patterns of life. This led to the first draft of the script revolving heavily around Koyasan and the role of faith, but when she moved to Kyoto, the setting of the drama shifted as well.

As she developed the script in English, Tillack worked with a translator to bring her message through to the final Japanese dialogue. Understanding the effect that the nuance of Japanese language would have on her English draft was an essential part of writing, she says. In the end, the actors themselves provided helpful adjustments to give the dialogue a natural and meaningful tone. Still, there are moments when the western influence is felt, like when Ami’s words come off as uncharacteristically sarcastic or in a scene featuring a public kiss – a moment that even the Japanese actors thought too unrealistic.

As the action unfolds, audiences are treated to a glimpse into modern Kyoto life. The choice to avoid typified Kyoto visuals must be applauded, as the film ignores tourist spots in favor of a subdued look at the backstreets of the city. Shot in the area around Nijo Castle and Horikawa, the deserted narrow alleys of the Nishijin textile district are a charming stage for the film’s love story. The minimalist but inviting locations allow viewers to better focus on the characters, with the help of tight shots and evenly paced editing.

Beyond the love story, there is a lot to unpack regarding the film’s themes. Hayato’s struggle to find a country where he fits in as hafu is a perennial one that Japanese media still shies away from. Tillack says that this is the way in which most foreign viewers connect with her film, and it best highlights the changing cultural landscape of Japan. Japanese audiences, however, may find common ground with Ami, who represents solidified tradition and resistance to change. Tillack uses these characters to show how Japan as a whole is stuck in a Showa Era mentality, an existential crisis that she feels is a very real threat to the future of Japan.

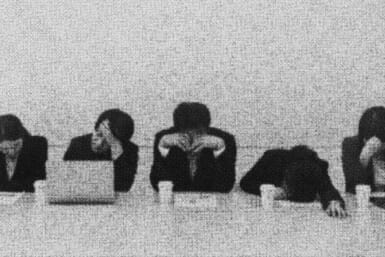

Tillack affirms that the theme of all that she creates is always ‘Where is Japan going next?’ Impossible to Imagine is a strong vehicle for her to raise a number of social issues that are scattered among the subplots; arranged marriages, overtourism, generation and gender gaps, and the hardships of a salaryman lifestyle. Without offering overt solutions or getting too preachy, Impossible to Imagine instead simply raises questions about these issues in hopes that it can spark a discussion. Screenings in Japan have led to some heartfelt conversations, giving the director faith that Japanese people are more opinionated about social changes than they let on in public.

As a solid feature debut, Impossible to Imagine demonstrates Tillack’s skill as a writer and director. It was a communal project, she says, that saw that the cast and crew coming together to support each other. The result is a charming indie film that breaks little new ground cinematically but offers up refreshing insight into what it’s like to be Japanese – in full or hafu – in Kyoto at the start of the Reiwa Era.

Impossible to Imagine can be viewed in Japanese on Amazon Prime, or with English subtitles via rental on Vimeo. To see more of Tillack’s work, visit her channel Where Next Japan on YouTube.