Hideyasu Moto published his first comics in Garo, underground manga’s cult favorite magazine, in 1995. The magazine had peaked in the ’70s, but the meeting of Moto and Garo would yield some of the defining works of the artist’s career.

Garo is known mainly for its more gritty stars like Yoshiharu Tsuge, Yoshihiro Tatsumi and Takashi Nemoto. Comparatively, at least upon first glance, Moto’s manga are sweeter, populated by babyish and beady-eyed creatures (his dog Mocozo makes frequent appearances). But under the sweet first layer is much anxiety and cynicism. An uncanny runs through the idyllic landscapes in his illustrations, similar to the aura of a cabinet of dolls, or the blank stare of a stuffed animal. Maybe the plushy exterior is a facade sewn over something more mischievous or even sinister.

View this post on Instagram

Moto, who debuted as an illustrator in 1990, told me that his Garo debut five years later marked the development of his own style. “I guess I was sort of contrary, and I didn’t want my works to be seen as fashionable, so I deliberately kept my style unfashionable,” he said, a bit self-deprecatingly. Though I wouldn’t call his illustrations unfashionable, they certainly display an admiration for the past: You see calls to modernist painting, palettes reminiscent of three-strip Technicolor, portraits of George Harrison and RZA, pop references like city pop and Ultraman. Even his manner of handling acrylic paint – opaque, smooth, very flat sometimes, or emphatically gradiated – is lovably “unfashionable,” like a Showa Era poster.

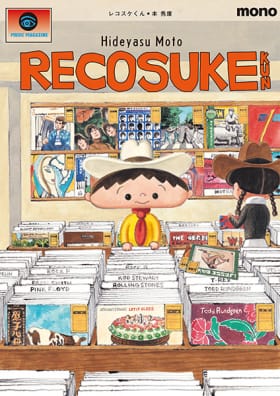

Unsurprisingly, Recosuke-kun, his most famous manga, was about analog records. Recosuke-kun began as a serialization in Music Magazine and Record Collectors. Over 20 years later, the titular protagonist continues to appear in his works, from standalone paintings to T-shirts. He speculated that he keeps getting requests to draw Recosuke-kun from the “many analog record lovers out there.” Luckily, history and our tastes are cyclical and what was newly outdated in the ’90s is vogue again. It’s as if Moto predicted the popular revival of old-fashioned sounds and warm, old-fashioned colors and characters. Were you inspired by ’90s music and fashion at this time? I asked. He answered that he always preferred music from before he was born, like The Beatles. Especially George Harrison.

Courtesy of Hideyasu Moto

The pretense of paying no mind to the ebbs and flows of fashion is fashionable, though the artist seems to have maintained a natural indifference throughout his career. Through Recosuke-kun he gushes about music, and his more recent compositions flout modern standards of structure and order. In the way of Magritte, an odd, radical symmetry and stiffness often dominates his mishmash character paintings. Overlarge, warped heads, screwball hybrids and surrealist scenes, when rendered in the nostalgia and politeness of his painting method, come to life, no longer mere deliberations on magazine paper.

Before I talked to Moto, I considered comics a necessarily rigid medium, more regulated in both form and dissemination than standalone paintings and illustrations. I thought, those artists must draw in boxes, and put those boxes in bigger boxes, and be subject to the eye of editors and publishers. However, Moto likened underground comics to fine art, “where the artist is allowed to draw freely.” He said, “Since it’s the exact opposite of commercial art, the motivation to create is different, and you can work on your piece with a fresh mind.”

Courtesy of Hideyasu Moto

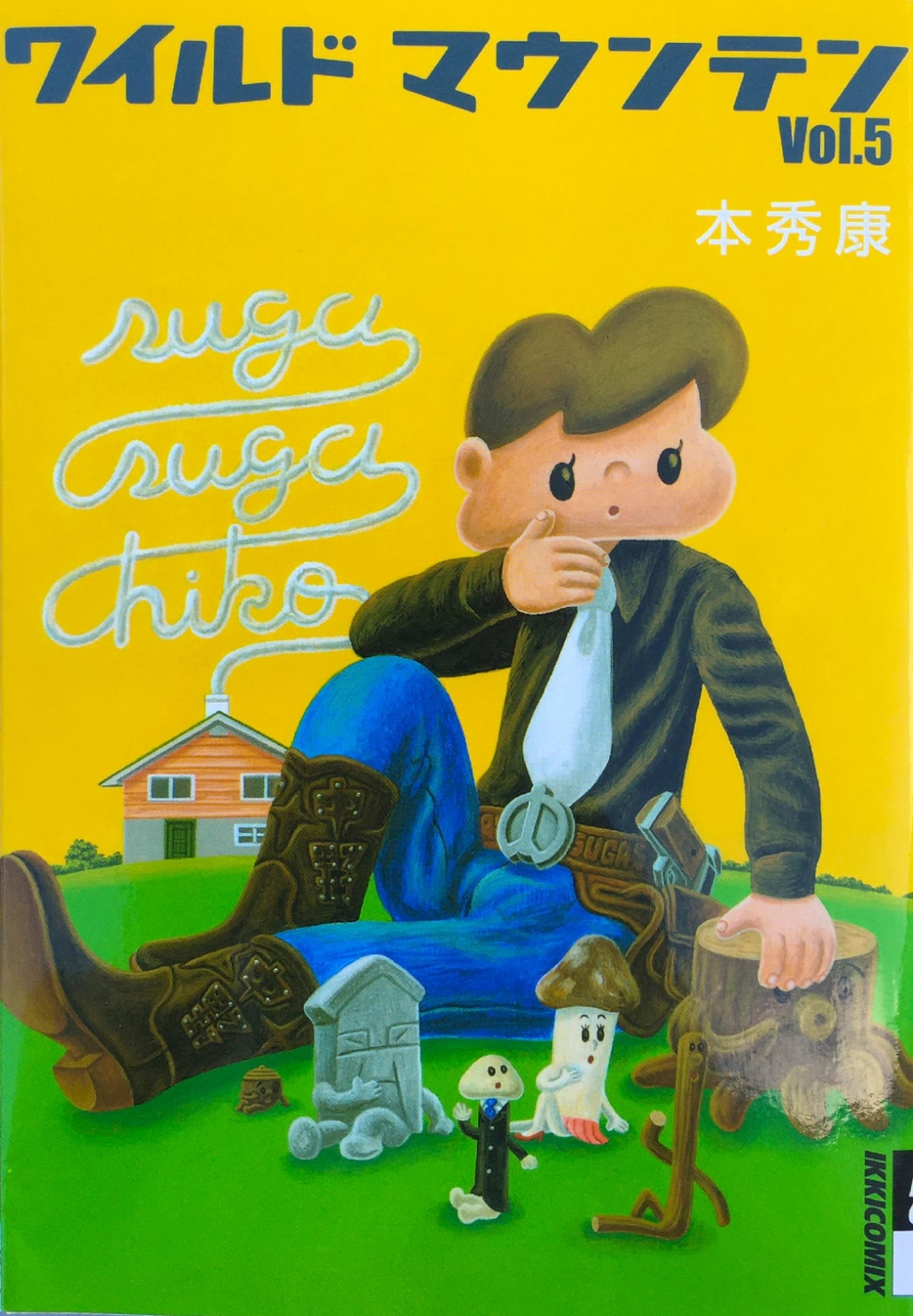

The outlandish canvases and illustrations of his later career, then, are not a reaction to any restraint in his comic days. The phase of his career when he was drawing for avant-garde magazines like Garo and, subsequently, Monthly Ikki was actually highly independent. Comb through the old copies of Ikki on Amazon and Ebay and you’ll see the equally outlandish covers of Moto’s serial manga Wild Mountain. You’ll see wooded landscapes with big-eyed deer and anthropomorphic mushrooms, and read titles like “Nakano-ku Fantasy” and “Alien Invasion of Nakano-ku’s Wild Mountain Town!?” Just as Recosuke-kun appears time and again in new projects, the meadows and cityscapes of Wild Mountain laid the formal foundations of the glossy Technicolor world Moto paints today – which is never subject to the influences of contemporary fashion or artistic canon.

View this post on Instagram

Music is as important to his work as these fantastical visions. Realizing his Recosuke-era infatuations, Moto’s oeuvre has come to include many album covers and even his own music label. In 2014, on his 45th birthday, he founded Rhion Records, which releases 7-inch singles with original Moto-made covers. The smaller vinyls are both less expensive to make and easier to draw covers for. “That’s how I became a 7-inch record specialist,” he explained.

He has done collaborations with the likes of never young beach, cero and Kaneko Ayano, as well as doo-wop pop singer ℃-want you!. Record covers cater to the artist and song, of course, but Moto does not distill his style to conform to commercial-aesthetic ideals of minimalism and sleekness, often setting the likenesses of the artists against his characteristic pastoral landscapes, or venturing into superflat plays of stark line and color. He is not lucky that these retro fairytale visions are in favor today; he would not care if they actually were unfashionable. Moto is not just indifferent to fashion, but above it. He knows what he likes. Sometimes, his process is as simple as one song. “Whenever I paint, I make sure to put music on,” he shared. “When I listen to a gentle song, it makes for a gentle picture, and when I listen to a dark song, it makes for a dark picture. I think of music as a painting medium.”

An exhibition featuring the dog-portraits of Moto and others, with Mocozo as muse, will take place at 888books from September 17 to September 27.