More than a decade ago American businessman Michael Howard obtained a job as an international sales manager with one of Japan’s top conglomerates, becoming one of a handful of foreigners working in a company of 50,000-plus employees. Over the next 10 years Howard worked at four different Japanese companies, learning the ins and outs of life as a Tokyo salaryman. He learned how to take a nap on the train. He learned how to booze on an empty stomach and build a secret money stash.

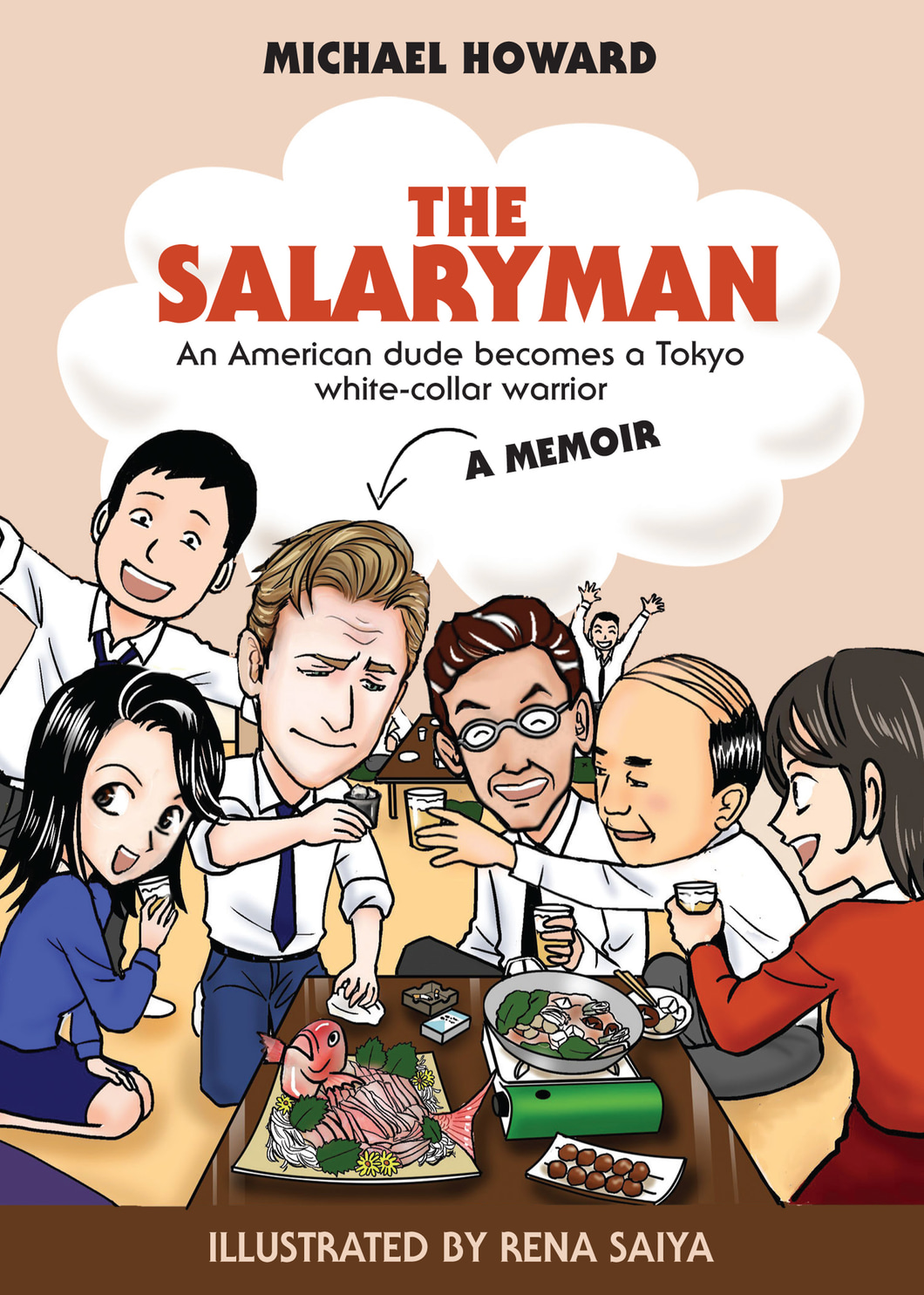

All this and more is chronicled in Howard’s self-published book appropriately titled, “The Salaryman: A Memoir.” Illustrated with manga artwork by Rena Saiya, Howard’s first book is fun, digestible and relatable, without holding back on the nitty-gritty and at times painful episodes endured by the typical salaryman. Howard stopped by the TW office to take us deeper into this world inaccessible to most foreigners.

Illustration by Rena Saiya

Why did you feel these experiences are worth sharing?

I think few people go as deep into that world of hard-core, traditional Japanese companies. I just wanted to write something that was an attempt to define some of the things that I came to find are part of being a salaryman in a modern era and how that plays into being a foreigner here.

Many of us foreigners in Tokyo we sort of circle around that salaryman world. We get to know salarymen as friends, and we kind of dip into it every now and then, and we judge from the outside, but how did you manage to inject yourself directly into the salaryman life?

It was sort of by no choice. I was living as they did. I had an allowance from my wife. I was dealing with the same things the others were, as far as I had to follow company rules. I sort of went along with it and thought to myself, ‘I have to learn half of this at least.’

You talk a lot about adhering to the “manner mode” principle. What is your interpretation of manner mode?

It’s everything that you have to be to be a good Japanese citizen that you learn through your upbringing. Where to sit on the opposite side of the meeting room. How to exchange business cards. How to kowtow in a way to your senior bosses to make them feel comfortable at all times. These are all things that junior employees in a Japanese company understand innately how to do. That is totally counter-intuitive to us as Westerners. I think that manner mode to me was basically a personal philosophy on how to get through the day.

I found myself exhausted halfway through the day for the first year, because, one, I didn’t know how to nap.

You talk about following manner mode in the office, in the elevator, in the izakaya. What are some of the tips you can share with fellow salarymen-in-training who are trying to learn some of these same lessons?

It takes a lot of energy to be so polite. I found myself exhausted halfway through the day for the first year, because, one, I didn’t know how to nap, so I had a sleep deficit. Two, I didn’t know how to enjoy the consumption of Japan like a Japanese. You have a lot of services catering to you as a salaryman here, not through the R-rated way, but every restaurant you walk into, you feel everything is catered to you. You go to the izakaya and you can have a bottle there that is just for you. You can yell from across the room at a waiter or waitress and they will right away run over and fill up all of your glasses. As an immigrant, you are trying to be on your best behavior. But in those scenarios you have a lot of empowerment. Learning how to yell ‘sumimasen’ in the right way, for example, is just one of 100 ways you learn how to take advantage of your role in society.

You received a lot of notes about your behavior at work, whether it was your method of tearing toilet paper or method of cleaning your desk. How did your colleagues go about improving your salaryman manners?

The toilet paper, I was on my own… A couple of times a senior manager would see me get frustrated and lose it a little bit. One time I did have an argument with a boss who didn’t realize I had a journalism background. He was trying to write all the slogans for the company, and I sort of lost it. I said, ‘Didn’t you read my resumé at all?’ I just sort of walked out and another manager found me and he was just like, ‘Mike, he is very proud of his English, and you sort of confronted him in a way that wasn’t comfortable. We know you are right, but don’t act like you are right.’ People grab your arm like that. Any sensible sort of professional does that.

Illustration by Rena Saiya

What are some of the salaryman traits you haven’t been able to adjust to?

The meetings. I work at an American company now. I graduated. But, still even in an Americanized, international environment – mostly Japanese in the office – they still have an ability to extend meetings to the time that was allotted. If a meeting had a 30-minute time set to it, but really it’s done after 10 or 15 minutes, there’s still this sort of badmintoning of a birdie around that goes for another 15 minutes. Then everybody seems to automatically know once 30 minutes is up, and they all get up, and I am still sitting there. I’m just still getting used to the rhythm of the ceremony of the meeting.

Traditional Japanese business isn’t as stable as it has always been, and people were coming to terms with that.

Since your time in Tokyo, have you seen any evolution in the salaryman world?

I do see, as my years went on in these Japanese companies, fewer and fewer cases of people who imagined staying there their whole careers. I think the Lehman shock and the few years after that had something to do with it. I noticed a lot of mid-management moving around, and the people coming in were younger and a little different from the older Japanese that were leaving or having to be let go. I did notice that there was more acceptance that the world had changed a little bit. That traditional Japanese business isn’t as stable as it has always been, and people were coming to terms with that.

Do you think the salaryman gets a bad rap?

I do. I think the villain, if there is a villain in the book, it’s not the salaryman. I learned to be more sympathetic towards the idea that people are people. It’s the institutions that are a little different. There is an understanding that I now have about why salarymen work late and can be seen at a tavern maybe later than their Western colleagues. It’s not because they care any less about their families than we do. There’s peer pressure and maybe a motivational vacuum caused by the formality of companies that causes that need to consume. That consumption gets a bad rap. One of the jewels of Japan is the retail economy. It is a blast to be a consumer in this country. The goods and services are just awesome. Who’s to blame them for enjoying all the foods and alcohols?

Did your life as a salaryman have an effect on your home life?

Yeah, absolutely. The last chapter, I get to it. I did get divorced over the course [of my salaryman career]. This is I think one of the things that happens when you take out the value system that you were brought up with and try to superimpose another set of values onto it. I developed a little bit of a bitterness probably about what I might have given up by moving here. Even though Japan was always good to me. I always found another job. People did open their doors and allow me to interview. There’s always that element of, I didn’t have to have it this hard. And I had pressure to fit in from my spouse. To just fit in. ‘What’s wrong?’ That’s an element of what broke down. We do have two children here. Japan is great for kids and with kids. Maybe book number two is diving into what it’s like to be a parent here.

Find out more about The Salaryman: A Memoir on Michael Howard’s website. The paperback is also available for purchase on Amazon: mybook.to/TheSalaryman