Can Japan stick its moon landing before the 2020 Olympics?

By Kyle Mullin

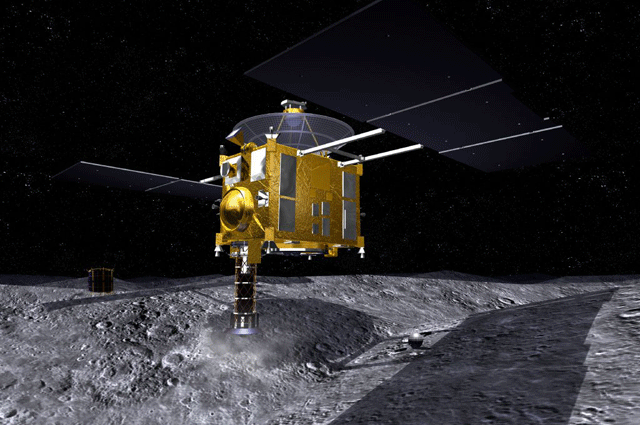

By 2019, JAXA hopes to put its first lunar landing operation into motion. The project will involve the use of a rover called the Smart Lander for Investigating the Moon (SLIM), which will be used to explore lunar craters and rock formations nearly five decades after Neil Armstrong first bounded across that craggy, low-gravity landscape.

The Mars mission began in 1998 but was scrapped in 2003 because of “technical difficulties and a lack of… technical savvy” according to the Guardian Liberty Voice. Meanwhile, Tech Times notes that previous moon landing efforts were plagued by subpar technology that caused the intergalactic vehicles to miss “their landing targets by some miles.”

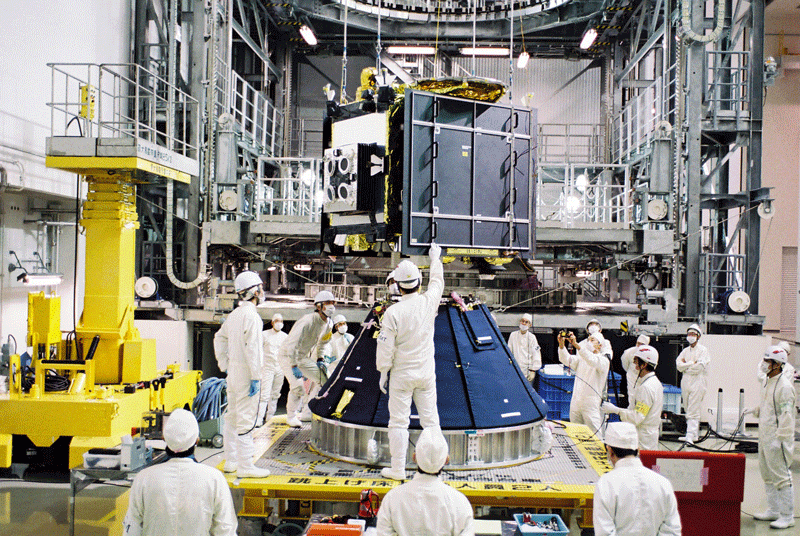

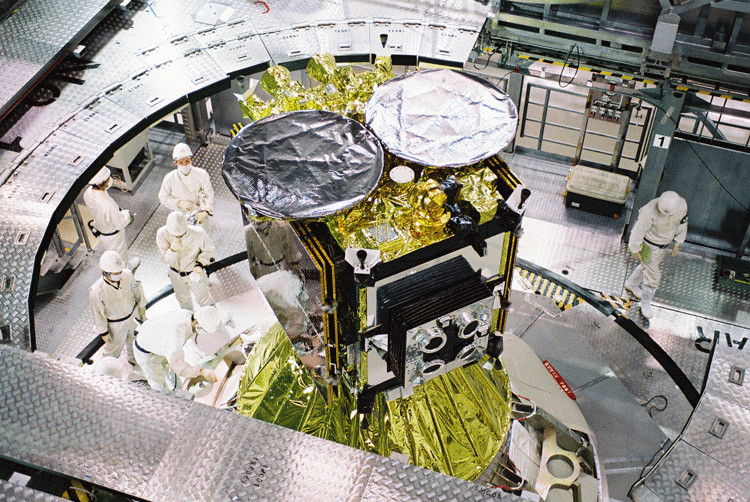

But more recent successes have emboldened JAXA in the lead up to the lunar landing. JAXA spokesperson Miyuki Takeishi tells Tokyo Weekender that “great strides” have been made, citing the success of the seven-year Hayabusa mission, “the first to perform a sample return from an asteroid.” Its successor, the Hayabusa2, launched late last year.

But Yoshiki Morino says Japan, and the rest of the world, are still falling short of their potential as lunar explorers. A professor at Waseda University, (which has a comprehensive partnership with JAXA and aerospace roots that extend back more than 70 years) Morino notes that, despite the success of Japan’s SELENE (aka. Kaguya) moon orbiter mission dating back to September 2007, but adds that more extensive successor mission “has not been deemed a high priority for space science and exploration missions… (so) the project has been scrapped.”

Despite that disappointing state of affairs, Morino does admit that there has been a resurgence in Japan’s space endeavors, particularly in the form of projects that with lower operating budgets. One of them is the September 2013 launch of a new “Epsilon” small rocket system, “which has already put small satellites into space at a low cost, including the 2014 launches of the global rainfall observation satellite GPM and the the Land Observing Satellite ALOS-2 (colloquially dubbed the “Daichi No. 2”). Of course, a successful start for the Hayabusa2 mission has given the Space Agency a shot in the arm.

Asteroid missions in general have become a more popular target for many space agencies, and one that is seen as a “step forward,” according to Morino. According to some, the intent may not be one of pure research. For example, in 2013 NASA released a statement in which the “…authors made strong references to the threat asteroids pose—along with the fact a large amount of NEOs (near-Earth objects) remain undiscovered—as an emphasis on supporting of such a mission from an Earth protection standpoint.”

However, one astronaut from space exploration’s Golden Age says asteroid landings are not merely an effort to prevent potential disaster flick scenarios from devastating the Earth. In a 2011 interview with Universe Today, Apollo astronaut Rusty Schweickart argued that asteroid landings can also serve as an exploratory stepping stone: “It will focus … attention on we humans extending our capability beyond Earth/Moon space and into deep space. This is an essential capability in order to ultimately get to Mars, and a relatively short mission to a near-Earth asteroid is a logical first step in establishing a deep space human capability.”

Morino agrees, while admitting that Japan would not be able to foot the bill for Mars missions by itself: “Mars is certainly the focus for international space exploration. Of course, given the sheer cost of manned missions to Mars, such missions conducted by Japan alone would not be realistic.” However, both the Hayabusa missions, and the planned SLIM project, showcase considerable technical achievements that can be done on a reasonable budget and that can serve as steps along the way towards more extensive, internationally collaborative missions.

From an economic standpoint, Morino says the SLIM launch plan, which has been tentatively scheduled for the fiscal year beginning in April 2019 (it had originally been slated for fiscal 2018, but has been pushed ahead one year), is a highly beneficial because it is unmanned, allowing JAXA to save on the cost of training astronauts, or building. He adds that the robotic rover will travel to the moon in a small, inexpensive Epsilon rocket. Even with this budget-friendly features, the entire enterprise is looking at a potential price tag of 15 billion yen ($126 million).

While this might make the SLIM launch sound like a no-frills affair, Takeishi says that JAXA hasn’t skimped on the mission’s landing equipment. In fact, this is where major advances are being made. “The biggest focus for the SLIM project is to develop system technology that will allow for high-precision landing, including advanced technology in guidance control and landing shock absorption systems,” Takeshi says, adding that such technology will “…make it possible to land exactly where you want to. This is an essential technique in the field of lunar and planetary exploration.”

This high-precision technology will help the SLIM stick its landing “within the intended landing site’s 328-feet radius.” Morino adds that this landing technology “could prove to be a major step in lunar exploration,” and as Japan and other space agencies keep their eyes set on heavenly bodies beyond our closest neighbors, it could prove invaluable as a means towards achieving mission success on more ambitious projects. “You might not consider it a breakthrough in the sense of pure technology, but it can be a small-scale revolution in terms of lunar and planetary exploration missions.”

Japan’s Space Milestones

Oct. 1, 1969: Japan’s space age begins with the founding of the National Space Development Agency, which adopted a strictly peaceful mandate and focused on developing, launching and monitoring satellites and launch vehicles.

Feb. 11, 1970: The first Japanese satellite, Osumi, is launched into orbit, making Japan the fourth nation—after the USSR, United States and France—to do so.

Sept. 12, 1992: Dr. Mamoru Mohri becomes the first NASDA astronaut to orbit the earth in the US Space Shuttle STS-47 as part of the American and Japanese collaborative SL-J mission.

July 4, 1998: The Land of the Rising Sun sets its sites on The Red Planet, as the the M-V rocket launches Nozomi, Japan’s first Mars-orbiting probe. Unfortunately, electrical failures hamper its journey, and the mission is scrapped in 2003.

May 9, 2003: The Hayabusa project, which made use of an innovative ion drive propulsion system, launched its way towards the asteroid 25143 Itokawa. It touched down two years later, and made its way back to Earth on June 13, 2010. It was the first spacecraft to visit an asteroid and return with samples.

Sept. 14, 2007: The SELENE mission was launched. The project successfully placed a satellite around the Moon’s orbit, where it remained until 2009.

July 27, 2009: Assembly of the International Space Station’s (ISS) Japanese Experiment Module (JEM), nicknamed Kibo (きぼう, or “Hope”) is completed. To date, it is the largest of the station’s components and features a robotic arm and modules for experiments and storage.

Sept. 14, 2013: Japan focuses on “affordable” space exploration with the premiere launch of its first small, low cost “Epsilon,” rocket. It replaced the larger, costlier M-V rocket, which was mothballed in 2006.

Dec. 3, 2014: The Hayabusa2 asteroid explorer lifted off. Called “the most ambitious mission to an asteroid ever attempted” because the explorer is designed to help scientists glean more information about how asteroids may have brought water and organic particles to Earth.

Main Image: illustration of the SLIM lander touching down on the Moon. (Courtesy of JAXA)