Jan Oberg was born in Denmark in 1951. He has a Ph.D. in sociology, focusing on peace and future research. His resume includes work as the former director of the Lund University Peace Research Institute; former secretary-general of the Danish Peace Foundation and former member of the Danish government’s Committee on Security and Disarmament among other peace-based work. His time in Japan includes being a visiting professor at International Christian University (ICU) and Chuo University.

He has some 3,600 pages of published material in academic works, including 10 books written, co-authored or edited, and he is a featured columnist in Nordic newspapers.

With his wife, Christina Spannar, he founded the Transnational Foundation for Peace and Future Research. He has been Chairman of the Board since 1997 and was head of its Conflict-Mitigation team to the former Yugoslavia and Georgia.

As armed conflict between U.S. and U.K.-led coalition forces and Iraq seemed to be becoming more likely, and anti-war protest demonstrations became more frequent in various countries, Tokyo Weekender had the opportunity to speak with Dr. Oberg and get his views on the world situation and prospects for peace—not war. The interview follows.

TW: Share with us what you actually do when you go to the former Yugoslavia or visit Iraq.

Jan: Well, I try to speak with people from all walks of life: presidents, prime ministers, counselors, media people, people of culture, history, taxi drivers and people in cafes. Everybody has a story to tell, and it’s through their stories I can begin to understand a conflict from more than one viewpoint.

This is the first step of mediation. You cannot help anybody solve their problems if you see it only from your own side, or from “one party’s” side. So you have to be impartial, be a good listener and work reasonably hard to get in contact with many different people.

TW: Why is that important?

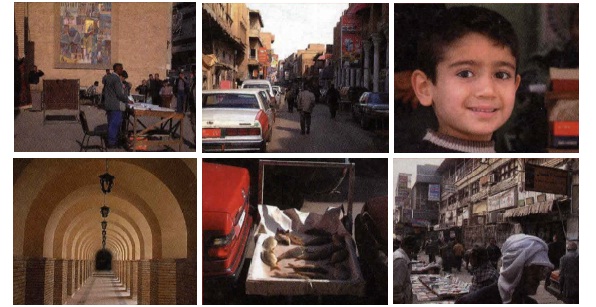

Jan: It is important because all war, all violence, is built on a kind of alienation from the harsh realities out there. Most people in the west would be unable to endorse or accept a war, say, on Iraq if they had known the people living there—their living conditions, their views, fears, hopes, their children, their educational system… If they had this sense of humanity that we are all human beings, it’s much more difficult to bomb, or conduct a war or kill. So killing by definition is something like keeping yourself a comfortable distance from the reality.

TW: There is always a danger in using the word “evil” to mobilize people. Can you elaborate on that?

Jan: If we choose primitive distinctions between evil and good, we define ourselves as good, which takes off the limits to what we might do in the fight against evil. If you really believe you’re fighting evil, then there are no limits to the weapons you can use, because you will eradicate the last bit of evil you see on the other side.

Eradicating evil does not mean to create a better world; you have to have a positive vision of how the world should be 20 or 40 years from now.

Now what do we think about the U.S. and George Bush today? Most people are dead scared. There’s no enthusiasm. We shake our heads and say, wow, where is this taking us?

TW: So it becomes an endless cycle of revenge, retaliation and hatred, leaving many people feeling powerless. Yet, you believe one answer is simple conversation?

Jan: Oh, yes. I always think when you have a decent conversation with another human, you sow seeds with each other.

We had set up a series of seminars for high school students, working with the U.N. in Eastern Slovenia and Croatia; it was the first time in seven years we brought Serb and Croat youth together. We had about 10 or 12 people, sitting in an oval, with Croat boys and girls on one side and Serbs on the other.

Remember, this is the first time they met, ever, meaning for half their lives they’d been in a war or in refugee camps and things like that; bad, you know. They’d not lived a normal life for half of their lives. We said to them, “We want you to tell a story about your individual suffering.”

Finally, one of the young kids started telling the story. It was a story like, “I was playing as a kid outside my parents’ house. I think it was a farm house or something like that, and suddenly I heard an explosion close to me, and I turned around and there is my little brother dead. He had fallen off his bicycle. It was a hand grenade that had killed my brother.”

We got each person’s story and found they were all people sharing their suffering. We finally got rid of politics, and we became human beings. We were not Serbs and Croats anymore in this setting, but people who had basically been through the same suffering.

So we found out, “they” are not a group – “they” are individuals, and I have no reason to hate this particular boy or that particuar girl, although he and she belongs to “the others.” So then we started asking, “Who actually has caused all this?”

Having gotten over this enormous emotional and problematic barrier, they could see it was their own politicians, parents and mass media. We were innocent kids.

The next step is to say, “We don’t have to hate each other anymore because you did not do anything bad to me. Maybe your parents did some bad to my parents and, of course, this is problematic but, at least, we sitting here are innocent, and have a chance of a more normal life.”

So the aggression, if you will, the guilt, was placed on their own politicians, and that I think is terribly important, because if we do not give children a chance to talk about their suffering, we make them implicitly guilty. Children carry the guilt of bad events for the family.

So when you give them a chance to overcome this, speak about it, and release the hate, then I think you can get to peace, forgiveness or reconciliation. I wish the same would be possible with grown-ups, but it is more difficult.

So funny enough, your question comes back to what we said in the beginning. The most interesting and the most important dimension of all this is human beings. After war, we can bring in bricks, build bridges, reestablish telephone lines, rebuild cities.

We can give them World Bank loans and all that, so we can repair physical structures, infrastructure, houses, but what we are obviously total amateurs and illiterate in doing in the international community is rebuilding the souls.

Rebuild the neighborhoods, rebuild civil society, and do something about revenge, hate, the feeling of humiliation and all that. And if we do not address these things as part of the peace and healing process after a war, or even before violence, then wars are going to be— exactly as you said—circles of violence.

So the stupidity of the international system is that it does not address the dimensions that are deeply human, but only the physical, material objects, the infrastructure.

And that of course goes with the whole question of whether dehumanization begins before war. To conduct war, you have to dehumanize people, and then you’re trapped yourself because, after war, you also forget these people are human beings. So you carry around all these bad, negative feelings and you end up destroying your own life, not just somebody else’s.

This is the beauty of reconciliation and forgiveness—that to forgive somebody is a choice you make. It’s a rational choice. You say I’m forgiving those who did this to me and my family because I want to relieve myself from hating the rest of my life and destroying my own life.

It’s an intelligent thing for the future to give up your head. And that’s where truth and reconciliation commissions can be helpful – it can recognize the suffering of people, they can let people speak so they can then get rid of the wish to hate and experience the power of forgiveness.

‘When we see someone who is

different, we should treat them as special.

There is much we can learn from them.’

Forgiveness is an individual thing. Nobody can ask you to forgive; you decide you want to forgive, and then reconciliation means you also stretch out your hands. It’s a powerful thing.

Consider some examples: You probably know the picture of the little Vietnamese girl running, burning with napalm on her back. She came to Washington in 1997 – still in pain – and gave a speech at the War Memorial. And one of the participants in that huge group was the pilot who thought he had thrown that napalm bomb from his plane.

He had left Vietnam, totally disillusioned, his family did not understand him, he had enormous guilt, he became an alcoholic, and then he began to study theology and became a priest. Now here was a chance to meet this woman, grown-up, 25 years later.

After her speech he runs up to her, grabs her, and says, “Can you forgive me?” And she knows exactly who he is the moment he says that, and she says with a weak smile to him, “That I did long ago.”

Remember (Nelson) Mandela, coming out from 28 years in prison… He says the prison guards shall sit on the first row, and people were surprised. Prison guards? “Yes, because they are my friends. They cared for me when I was in prison.”

You know, we should study these individuals who have been able to switch to peace, reconciliation and forgiveness from hate and revenge. There is almost no research in the world on these issues or these stories. This is mind-boggling to me because, while governments spend billions of dollars on developing new weapons and understanding warfare, not one percent of that is spent on understanding peace, reconciliation and forgiveness.

TW: But still there is hope because there are the children who can be educated, who can think like global citizens. I think that’s a very important message to convey to parents and teachers; that this is how they can contribute because children should grow up together without bigoted or rigid views about the world.

Jan: This is why the concept of loving kindness and compassion becomes important-to learn to see the world as one community.

Being able to see that any human being around the world is a fellow human being and not just my neighbor back home or some other citizen of my own nationality, that’s what I would call civilization. If we would care as much in principle as we do for those far away and the suffering people, as we do for those close to us, then this would be a beautiful world, and we have the potential to do that.

That’s what we can bring into education; to be world citizens, to cultivate non-violence, an alternative to violence, but it’s studying, it’s education, it’s training, it’s practical skills.

It’s going to war zones to learn the trade of talking with people and showing confidence, and also solidarity. Hey, I want to hear your story, I think you are in trouble, I can see you are suffering. Tell me your story, and I can maybe tell somebody else that story. It’s a basic human thing. I don’t know whether it leads to peace; it might well be that a few weeks after we’re sitting here talking there’s a war.

You know, there is curiosity about the foreigner, the man who comes and looks and is different from us. Imagine if we had politicians who would stand there waving, when they saw a foreigner coming, or the immigrants coming and saying, “Hey, it’s great you’re coming, we can learn from you.”

I do appreciate that refugee and immigrant workers and others can create problems and misunderstandings, and religions can clash and all that, but why must we always, at least in the west, talk about the others as a problem. They are an asset. Whenever you meet somebody who is different, you can learn something.

What I’ve been saying today is that I think every human being is a peace movement. I don’t believe much in big organizations and their street demonstrations. I believe in every single individual making peace, doing good acts, humane acts, thinking of others with some compassion… It’s simply what is going to change the world.